September 12, 2018 |

October 9, 2018

The frontiersman Daniel Boone first blazed a trail through the wilderness of the Cumberland Gap with an axe and his trusty rifle, Ticklicker, by his side. In the centuries that followed, generations of trail blazers knit a lacework of trail systems across the 450-mile long Cumberland Plateau. Crisscrossing four US states (Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia), its trails wind through lush Appalachian forests, climb rugged mountains, and wander along low-lying plains. The plateau’s waterfalls, natural bridges, and scenic views make the region a hiker’s paradise.

The Cumberland Trail became Tennessee’s 53rd state park in 1998, and the state’s only linear park. For the past 20 years, trail builders have been working to build the 300-mile Cumberland Trail across the plateau, linking it to the Great Eastern Trail. It is hard work. Nevertheless, volunteers join crews to cut branches, move rocks, build walls and bridges, and rake duff. This age-old trail building process has recently taken a step toward modernity as trail builders and designers now use web apps for mapping, data collection, and analysis.

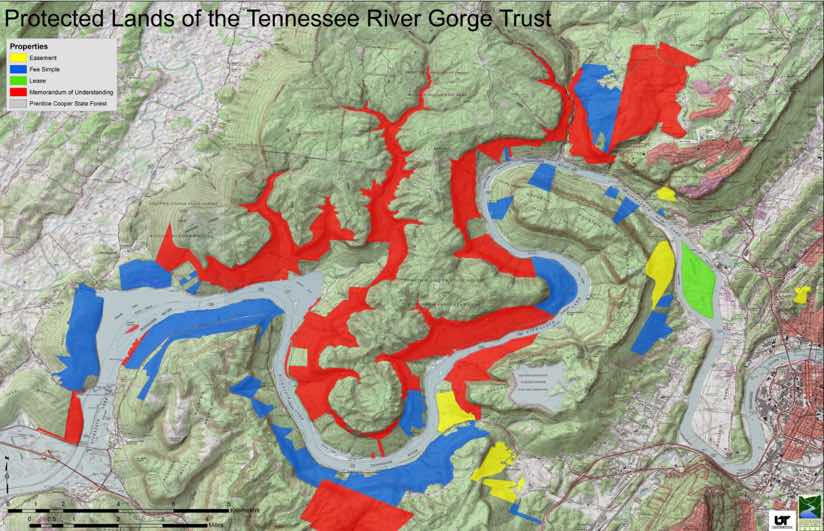

For example, GIS students and staff from the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, mapped existing trails and protected lands within a defined area. They rated parcels by conservation potential and added ratings to an online map. The map helps trail designers see where new trails would make the greatest impact.

Non-profit Cumberland Trails Conference (CTC) oversees the trail-building project, manages property acquisitions, and designs the trail. Now that the trail is 95 percent complete, the CTC team looks forward to the next phase: connecting the Cumberland Trail to rural communities and existing trail systems on public lands. They also want to analyze environmental corridors that support biodiversity.

For People and Nature

The trail network serves dual purposes, providing recreational opportunities for hikers as well as opening wildlife corridors to support biodiversity of regional flora and fauna. The region is recognized as a global biodiversity hotspot for amphibians, land snails, cave fauna, and vascular plants. Prior to the park’s creation, 90 percent of the land was privately owned, presenting one of the greatest modern conservation challenges in North America.

As a Tennessee state park, the Cumberland Trail is protected by conservation laws. By running the trail through animal habitat corridors, the CTC could ensure broader conservation in addition to recreation.

Often, plant and wildlife populations suffer from fragmentation and isolation caused by human development. Without connections between natural areas, genetic diversity declines and extinction often results. Yet, by restoring and protecting existing habitat and providing linkages between areas fragmented by development, humans are helping plant and animal populations interact. And, as the climate changes, this habitat connectivity allows species to shift their geographic range.

With all of this in mind, the CTC team reached out to University of Tennessee at Chattanooga’s Interdisciplinary Geospatial Technology (IGT) Lab. They asked IGTLab staff to build geospatial apps that could help them identify habitat corridors. In addition to identifying isolated natural areas and connecting them to larger protected areas through land acquisition or trail building, CTC also wanted to see how corridors could connect hikers to campsites.

App for Mapping

Charlie Mix, who is the university’s IGTLab director and an outdoor enthusiast, jumped at the opportunity to work on the project with his students and help redesign trail routes and create a new online map.

Now, the IGTLab team updates the map each time they receive new data. Much of the incoming data is captured by a mobile app IGTLab developers built for trail crews to use in the field. Since trail crews mostly work in remote places, the lab designed the app for offline use. So, while crews build connecting trails they also collect trail data that CTC will use to protect areas surrounding the trails.

With funding from the Lyndhurst Foundation, the CTC bought tablets, loaded them with maps and the trail data collection app, and distributed them to trail crews. IGTLab interns taught trail builders how to use the app. At the end of each day, builders return their devices to the interns who upload collected data and add it to the map.

“At first the trail builders were skeptical about the app, but once they started using it, they loved it,” Mix said. “They see a map and use GPS and app tools to collect information. The next thing they know, they see a map showing the information that they just gathered.”

CTC now keeps a digital record of the project’s status and maintains access to current, online maps. The maps and visualized data help CTC staff engage stakeholders and potential land donors. CTC can also share data with other organizations such as the The Land Trust for Tennessee, The Nature Conservancy, and local conservation and trail building organizations.

“The mobile app provided a structure for us to record our field work, one that cataloged both the recreation values such as camping or swimming holes and the conservation values like forest cover and rare plants,” explained Robert Weber, director, Cumberland Trails Conference. “The catalog will be with us going forward, providing a basis for our organization to compare and rank various values to guide our upcoming decisions about acquiring and developing those corridors.”

Learn how organizations and volunteers connect with apps to create up-to-date maps using ArcGIS Online. Learn the step-by-step workflow to evaluate habitat fragmentation and propose wildlife corridors.

Image Credit: Painting of Daniel Boone escorting settlers through the Cumberland Gap by George Caleb Bingham [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

September 12, 2018 |

August 16, 2017 |

February 14, 2018 | Multiple Authors |