February 1, 2022 |

November 7, 2023

Following the attacks of September 11, 2001, a consensus in federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial government and law enforcement formed around the need for better information sharing.

The result was the creation of a network of information clearinghouses called fusion centers and the organization of the US Department of Homeland Security. Today there are 80 fusion centers across the US and its territories using technology to integrate and share data.

These centers have helped identify suspicious acts related to both violent crime and terrorist activity. They form a vital network of thousands of experts—police and firefighters, emergency medical services, and narcotics enforcement agents—working with private-sector owners of critical infrastructure and federal, state, and local authorities. Cities and counties with real-time crime tracking capabilities connect their data and camera feeds, adding a granular awareness from Real-Time Crime Centers that work with their fusion centers. GIS and other IT staff support the efforts by analyzing data and creating information products to guide decisions.

A lot of information fusing takes place. But ask almost anyone in these agencies, and they’ll likely say they could collaborate and share more.

“America operates law enforcement through 18,000 individual agencies that are islands,” said Mike Sena, director for the Northern California High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) — Northern California Regional Intelligence Center (NCRIC) and president of the National Fusion Center Association (NFCA).

Sena has a vision for a next-level geographic approach to crime fighting to not only create maps but also provide an up-to-date shared awareness of the location of public safety threats to all fusion centers and their partners across America. He cites the example of a school threats dashboard he created using GIS technology that revealed wide-scale incidents that investigators have repeatedly determined were hoaxes.

“One day we had over 200 threats to schools around the country,” Sena said. “We never would have seen the scale without visualizing input from nationwide data collectors. People were reporting threats in near real time, and we could see it on the map to figure out the extent of the problem.” Though the incidents still required a response, the ability to see the widespread pattern helped police officers take a measured approach—investigating and information gathering rather than immediately activating heavily armed responses.

Sena has navigated the complexity of data sharing across jurisdictions and domains in dealing with the overdose crisis. He currently works with a team investigating a large fentanyl distribution network in San Francisco with more than 260 dealers that move large quantities every day.

The operation involves multiple agencies and undercover officers who share a common operational picture to break up this nefarious network. Analysts use GIS to map key locations such as where dealers live, where they sell drugs, and where they have been arrested.

“I see GIS as a giant multilevel chessboard,” Sena said. “But we’re often playing checkers in law enforcement. We see the immediate target, and we jump on that, but we’re not going for the queen . . . the pieces that matter.”

As Sena sees it, GIS technology gives law enforcement an information edge.

“We’re dealing with organizations and groups of people that have unlimited amounts of money and know how to raise funds quickly with illicit substances,” Sena said. “We need to organize ourselves better.”

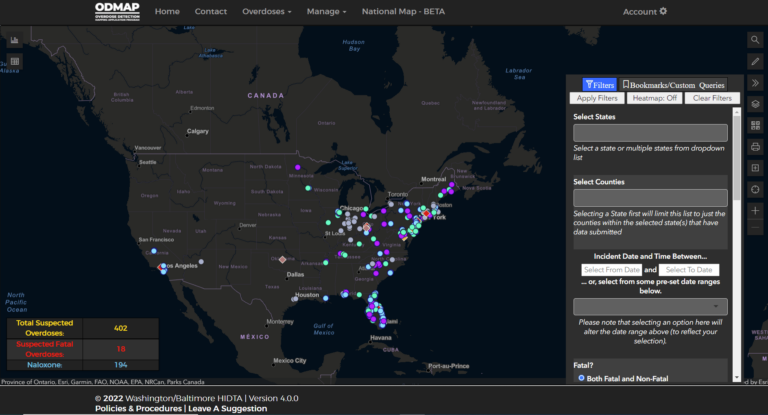

Sena learned from the experience of Director Tom Carr and Deputy Director Jeff Beeson at the Washington/Baltimore HIDTA as they deployed the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program (ODMAP) across the nation. The map provides near real-time suspected overdose data across jurisdictions to support public safety and public health efforts. It has proven effective in mobilizing an immediate response to a sudden increase, or spike, in overdose events. The same type of map-based alerts, Sena said, could be used for responding to shootings, robberies, organized retail theft, and burglaries.

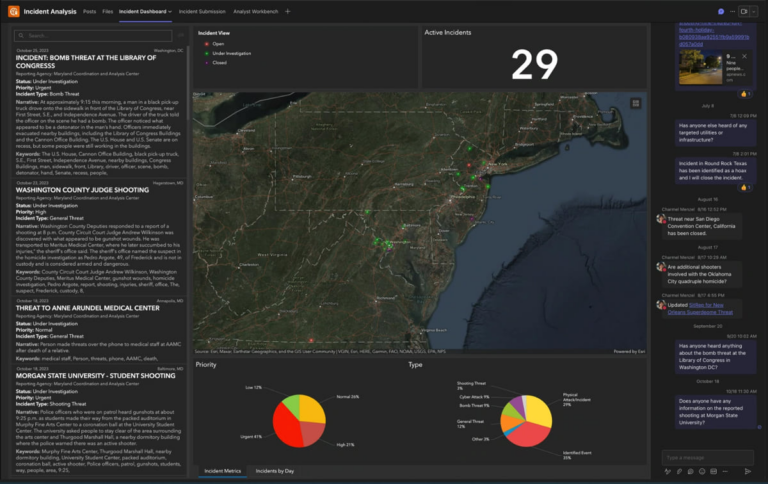

Sena aims to take the school threats and overdose dashboards to the next level. He envisioned a system for fusion centers to connect additional threat-related dashboards, adding alerts, collaborative tools, and even video conferencing. He reached out to Esri and Microsoft—companies that engineer two of the core technologies all agencies possess—to combine the best of Esri’s GIS map visualization capabilities with the collaborative tools of Microsoft Teams.

They created the Threat Reporting Exchange, or T-REX, as a proof of concept. It brings Esri and Microsoft platforms together in a collaborative space with a shared dashboard, an area for analysis, and a way to see real-time trends across the nation.

“We can share data and visualizations with 25,000 people in real time,” Sena said. “Fusion centers have never had that capacity before.”

Sena hopes to continue to refine T-REX and expand it to 100,000 concurrent users, with the ability to conduct real-time briefings for all fusion centers and their stakeholders in local law enforcement.

“The goal is to ingest data from whatever sources and pull it onto maps,” he said. “Ultimately, we hope to identify anyone who is causing harm to the community and a way to both see the threats and understand how to defeat them.”

Criminologists have shown that violent crime leads to more violent crime. The nationwide spikes in drug use, gun violence, and robberies are complex and interrelated. Sena would love to map all the dimensions of these issues—putting it all on a multilevel chessboard that all fusion centers, HIDTAs, and their partners can share.

“Mapping threats helps us connect all those islands with bridges of information,” Sena said.

Learn more about ArcGIS for Microsoft 365 and how GIS supports homeland security.

February 1, 2022 |

June 19, 2019 |

November 1, 2018 |