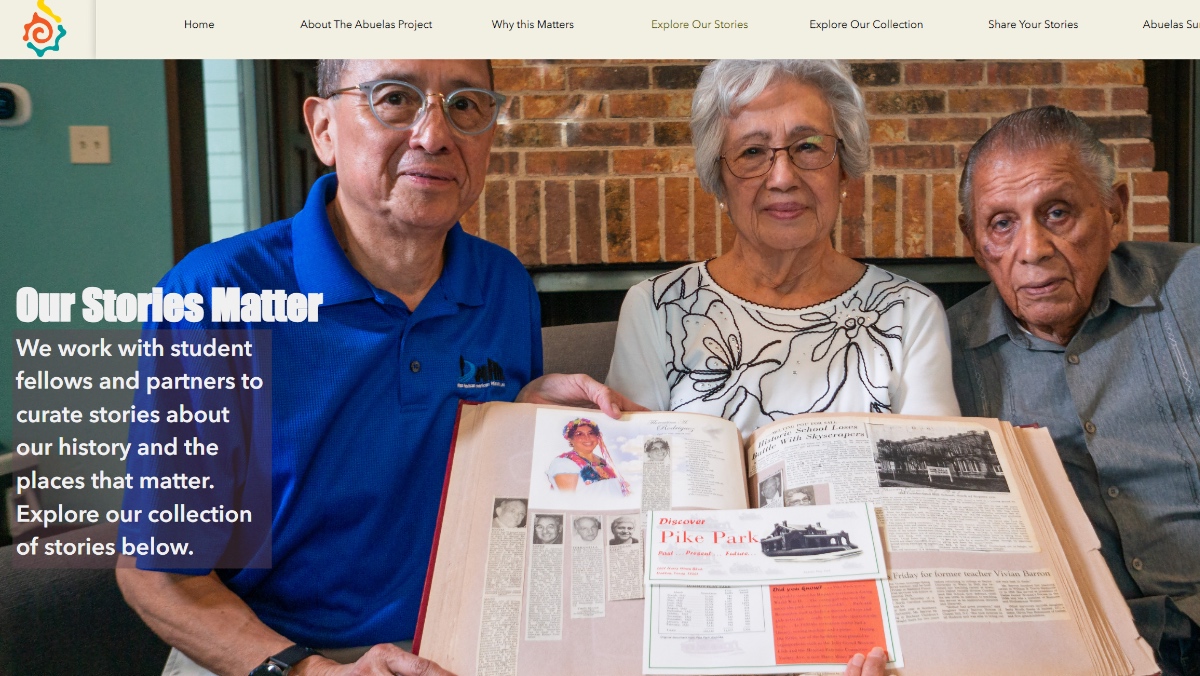

Heritage begins as a spoken story—shared across generations at the kitchen table, folded into recipes, woven into art, and rooted in the everyday places that shape our lives. The Abuelas Project, an initiative from Latinos in Heritage Conservation (LHC), aims to give those stories a larger audience and preserve them, using maps and other digital storytelling tools.

The project memorializes personal recollections from a farmworker who arrived in Texas through the Bracero Program—a guest worker initiative that brought millions of Mexican laborers to the US between 1942 and 1964. It delves into the roots of Conjunto music in San Benito, Texas, and it follows a flower shop that has flourished for over a century after starting in a family’s Albuquerque home.

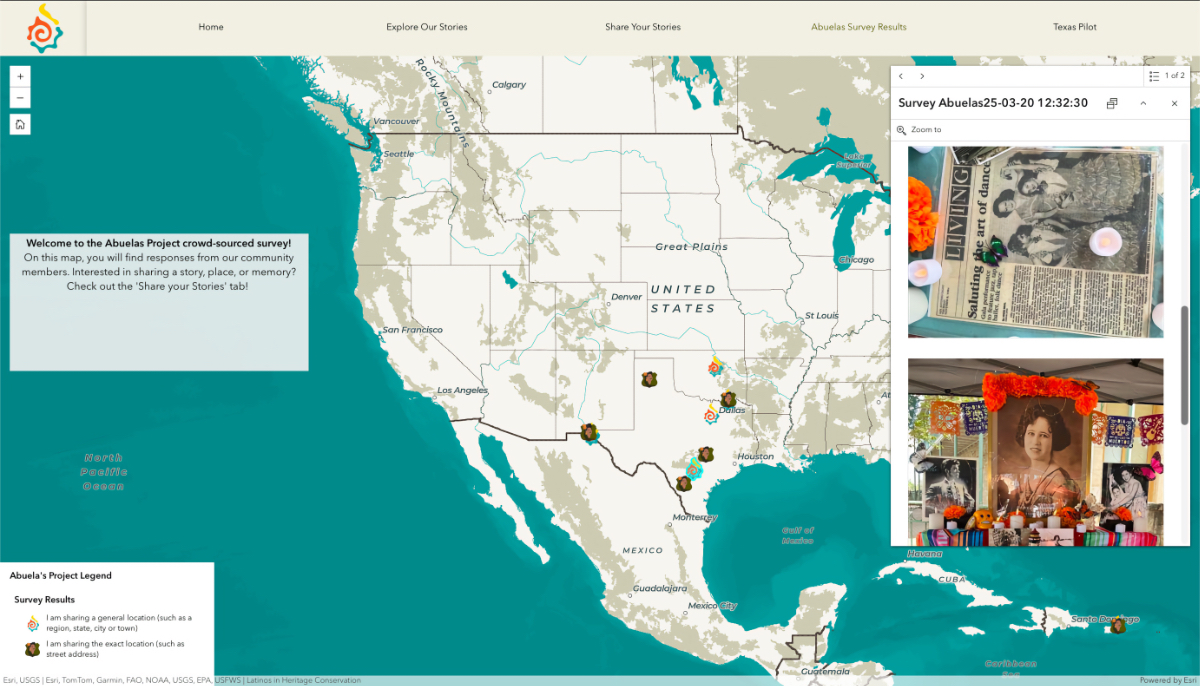

Today, the archive holds 26 oral histories, 40 hours of interviews, and more than 700 photographs and artifacts contributed by community members. At its heart, the project honors the grandmothers, “nuestras abuelas,” who have long carried the stories forward.

“Our grandmothers have always been the culture bearers, the story keepers,” said Sehila Mota Casper, LHC’s executive director. “We wanted to democratize historic preservation, recognizing intangible heritage like the oral storytelling from our grandmothers, their recipes, photographs, and historic sites that may no longer be there because they’ve been demolished, gentrified, or displaced.”

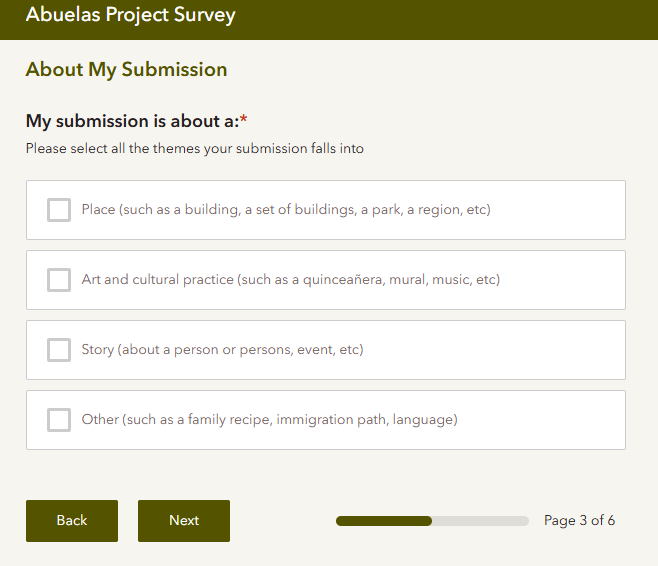

To create this living resource, the team blended formal records with stories and materials from the community. People shared their memories by filling out a survey on the site used to collect contributions. Each submission is reviewed to protect and present stories with care.

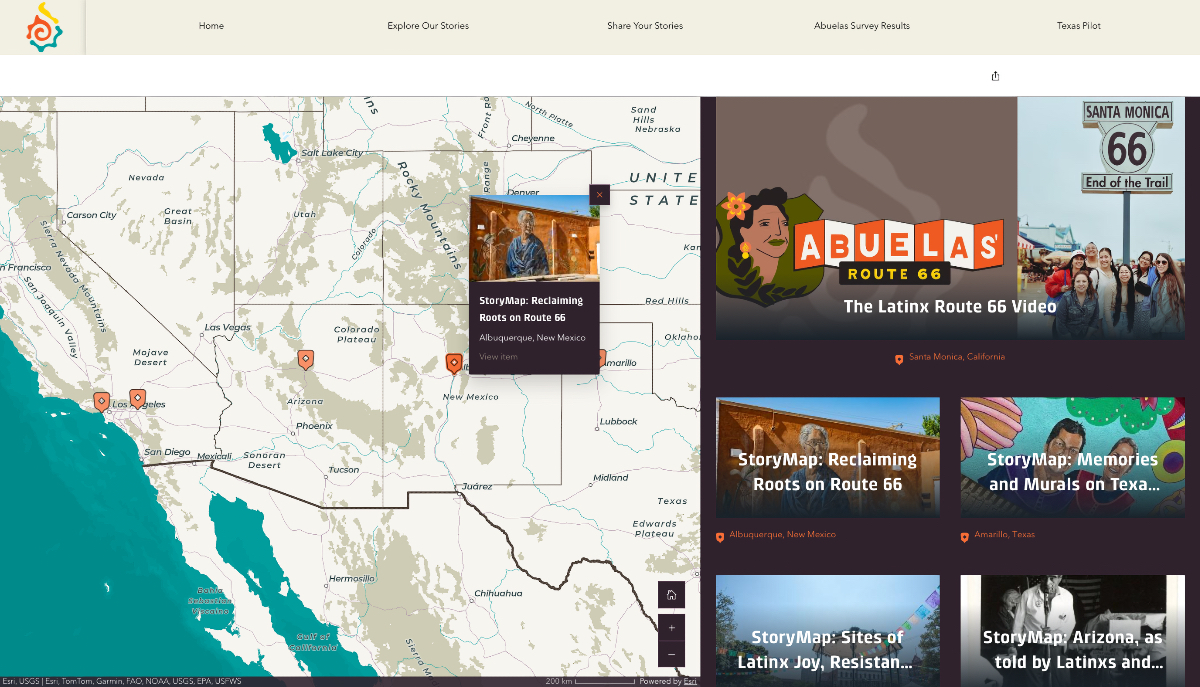

Drawing from this rich collection, the LHC team created multiple digital stories combining interactive maps, multimedia, and narrative text. More than 100 hours of research goes into developing every digital story, weaving together personal accounts and historical context.

Beginning in Texas, mapping experts and a team of student fellows called the Semilla Scholars (see sidebar), built a pilot map that captured places of profound meaning: from Mexican cemeteries and museums to beloved community landmarks. Visitors can hover over locations and learn more information about sites like Puerto de Baluartes, a Catholic mission predating the United States. They can see the West End Park and Dance Hall, home to weddings, quinceañeras, and packed concerts with stars like Lydia Mendoza.

From the start, LHC wanted technology that felt welcoming—something intuitive, web-based, and easy to navigate. It wanted to make storytelling tools simple for every user.

Accessibility guided each decision in this first map. High-contrast colors make the site easier to read, even for visitors with color vision deficiency. Elders on the board review language to ensure clarity, while younger contributors keep the platform fresh with embedded videos, interview recordings, and interactive features that hold attention.

“I always think about it being something my mother can use,” Casper said.

The archive feels like a multistory library: boxes of photos and maps in the “basement,” along with digital stories and audio on the “first floor,” with each level inviting exploration for users of all ages and skill levels.

The digital storytelling tool, ArcGIS StoryMaps, allowed the team to blend multimedia documents with maps powered by geographic information system (GIS) technology.

For nonprofits considering similar projects, Casper offers this advice: “You don’t have to be an expert in GIS. You just need the passion and cultural knowledge to stay true to your mission. The first try doesn’t have to be perfect—it’s an evolving process.”

The project’s reliance on crowdsourced stories and materials has highlighted lesser-known, but no less important, locations of historical significance. For example, one contributor shared that San Antonio was the first municipality in the US to host its own dance program, founded by Berta Almaguer in 1934. The San Antonio Parks and Recreation dance program has produced some of the city’s best dancers over the decades. The user contributed photos of news clippings and dance event posters, adding visual context to the city’s vibrant dance legacy.

One story collection, “Tejanos y más,” explores the lives and legacy of Mexican residents in Texas, including the story of Heriberto Cortéz who talks about his life as a bracero, one of millions of guest workers who came to the US. He was born in San Isidro, Oaxaca, Mexico, and worked on farms across Texas, Arkansas, and Missouri. In the digital story, he shares photographs alongside memories of his time in the US, from the joy he felt purchasing his first car to the difficulty of being the target of discrimination.

In another collection of stories focusing on Route 66, traveling west from Texas to California, the project’s map reveals places where communities were split or displaced to make way for the highway. It weaves together stories from untraditional landmarks along the iconic route, like the Red Ball Café in Albuquerque. The Latinx business welcomed travelers with the classic “Wimpy Burger” until 2024, serving generations of Route 66 explorers through changing owners and times.

Arizona claims nearly 350 miles of Route 66, and thanks to residents like Angel Delgadillo, it’s home to the longest stretch of the original road. The map traces how Delgadillo and 15 others sparked a grassroots movement, leading to the creation of the Historic Route 66 Association of Arizona. For 34 years, the association has worked to preserve, amplify, and protect this stretch for future generations to explore.

Following the route west into California, the digital story highlights San Bernardino’s Agua Mansa Pioneer Cemetery and how, after a devastating flood left many graves unreadable, community members and San Bernardino County Museum staff worked together to restore the cemetery. Using ground-penetrating radar technology, they cataloged and located lost graves, helping families reconnect with ancestors and keep these stories alive.

The Abuelas Project team will soon launch new digital collections. One will spotlight the Borderlands—communities along the US Southwest that share a border with Mexico. The second will showcase endangered Latinx landmarks across the US. These efforts help find, document, and protect sites at risk.

The project’s impact is felt in moments both big and small. Casper noted that contributors often begin their interviews by saying, “My story isn’t important.” But as they see their words and photos woven into the archive, they realize how much each story matters.

“There is so much power in being seen and being heard,” Casper said. “When a story is captured outside the family for the first time, it’s a big moment and an honor to be part of that.”

Esri supports a network of nonprofit organizations that are using GIS to create a more just, healthy, and prosperous world where everyone can thrive.