This is the second of a two-part story about assessing damages from the devastating tornadoes in Lee County, Alabama. The first installment focuses on quantifying the damage to receive federal assistance dollars.

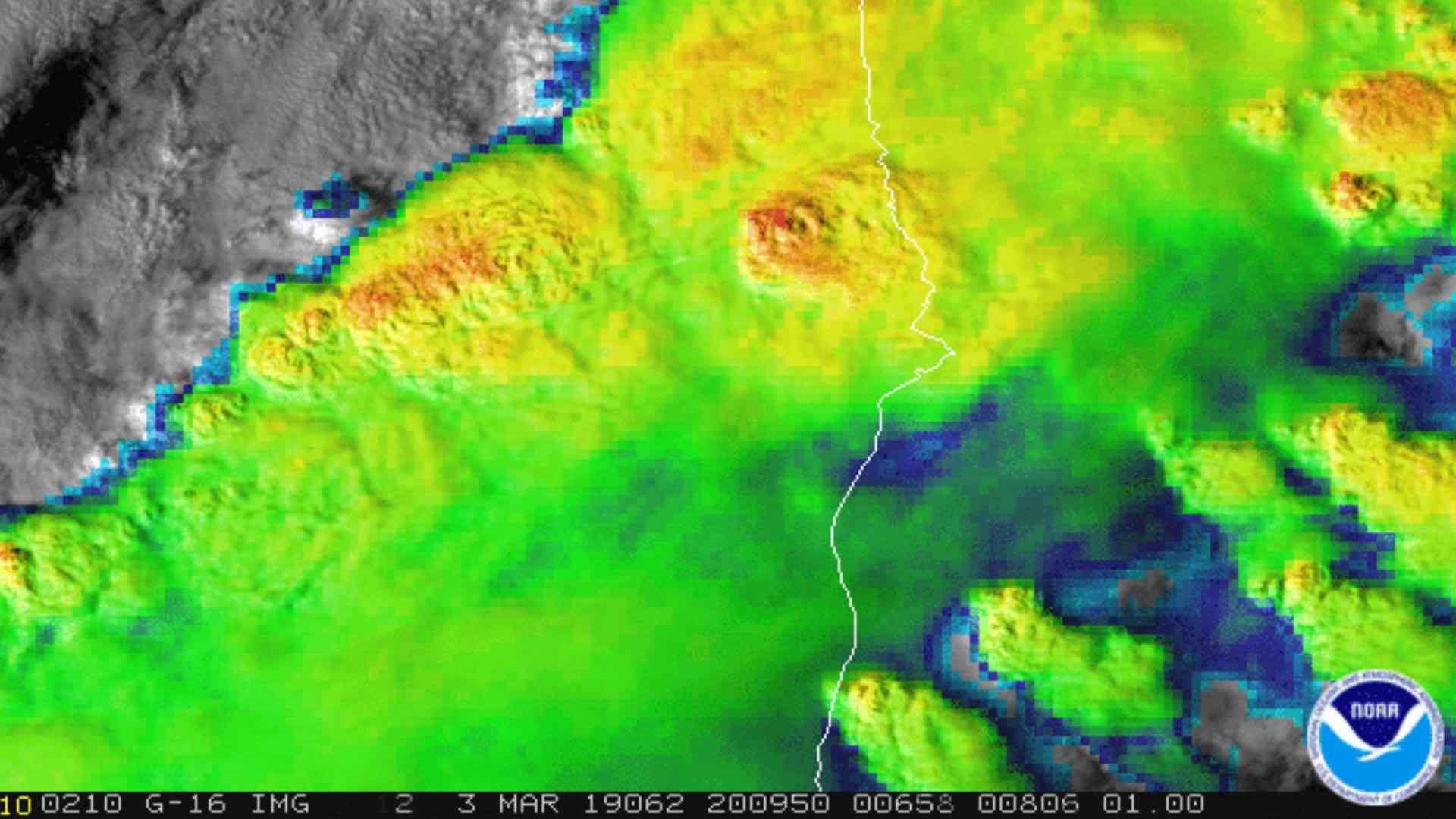

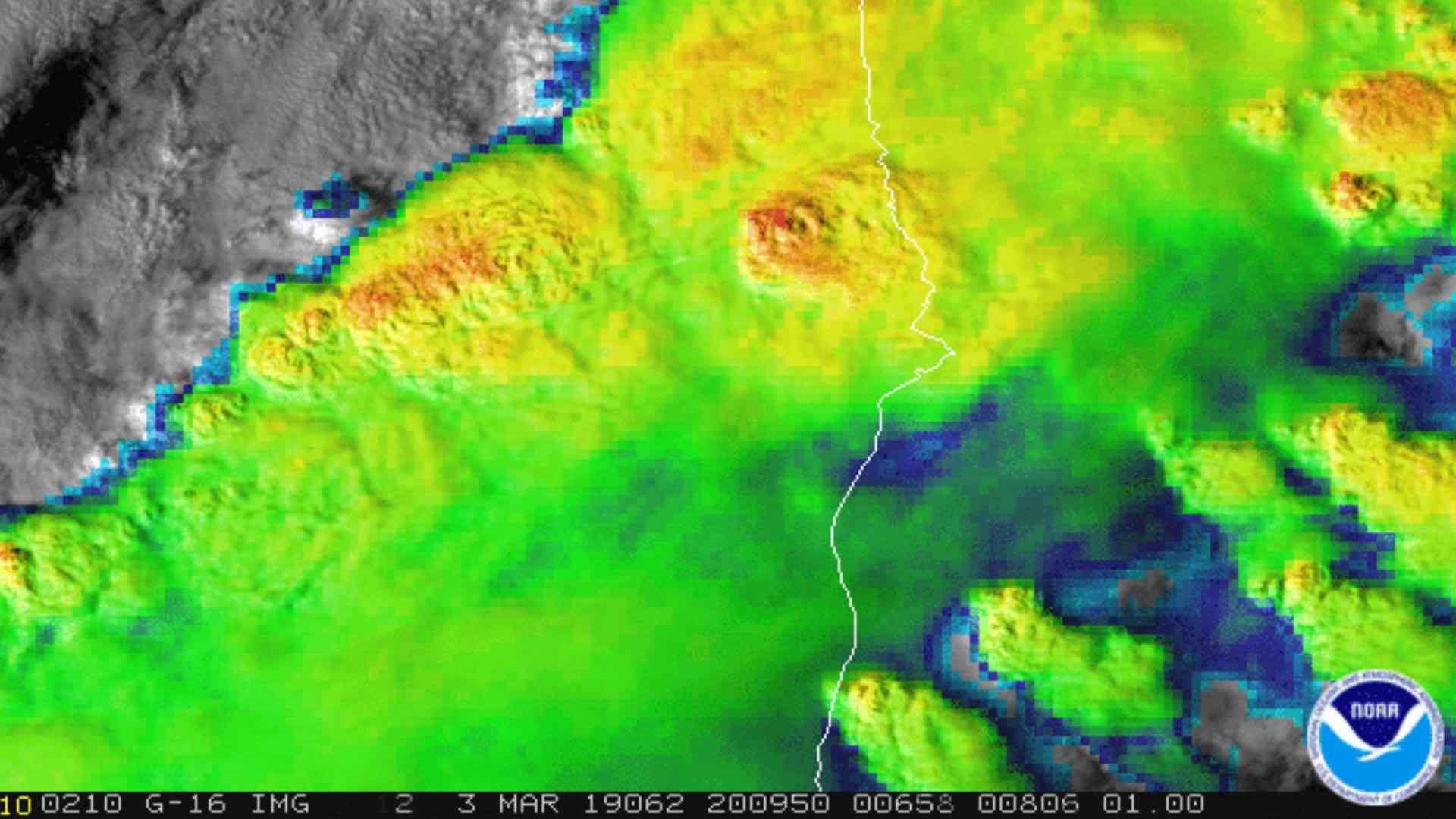

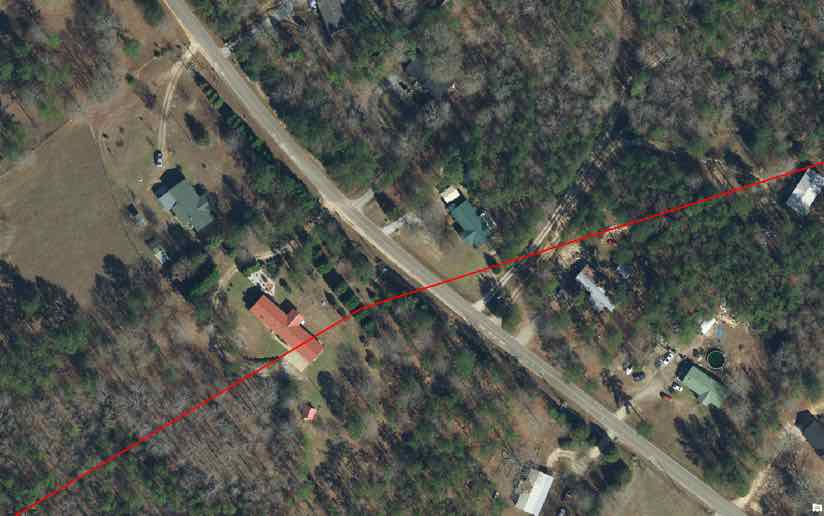

The scale and scope of two tornadoes that hit Lee County, Alabama in early March 2019 surprised many experts. Winds in the first tornado exceeded 170 miles-per-hour and left a trail of destruction nearly a mile wide and 24 miles long. The second tornado, though less severe, struck along nearly the same path as the first.

“This was the worst damage that I’ve seen from a tornado,” said David Thornburg, Section Chief, Alabama Fire College. “I saw 24-inch diameter pine trees snapped 20 feet in the air as well as at the ground, total destruction of mobile homes where the frame rails were left but nothing else was recognizable as a house part, and a house that was picked up and moved 30 to 40 feet onto a road.”

Personnel and students from the Alabama Fire College assisted Lee County’s Emergency Management Agency to assess damage and address survivor needs.

Ken Busby, the GIS Coordinator with Lee County, has first-hand experience understanding the plight of tornado victims.

“I have family who live in Sylvania, Alabama, and their house was completely destroyed [from the tornado that hit Tuscaloosa, Alabama on April 27, 2011],” Busby said. However, the Lee County event was the worst storm Busby has encountered as a mapping professional.

“My job is to try and get help out to those people, to make sense of the damage, and to support first responders with information and data they need to make decisions,” Busby said.

A modern combination of field apps and web-based dashboards from Esri aided the county’s efforts.

“It put the information in front of the people who needed it and gave them an understanding in great detail of what’s happening in the field without having to go out there,” Busby said. “They see from the office the full picture of the damage—where it is and where to send people.”

Finding Those in Need

Because of Lee County’s rural location, the recent storm impacted fewer lives than the Tuscaloosa tornado. But, where the tornadoes hit, they hit hard.

“You can see the power of this type of storm,” Busby said. “It’s like the hand of God came down and just wiped everything off the face of the earth.”

Busby equipped firefighters with a survey-based needs assessment app for recording and documenting survivor needs from the community. He routed data coming from the app onto a live dashboard in the Emergency Operations Center (EOC).

“We had a volunteer dedicated to monitoring that information, prioritizing what was immediately needed, and keeping track of less urgent needs like debris cleanup.”

Firefighters divided the area on the map into a grid, assigned the work to three divisions, and fanned out with five teams of two people per division.

“Rural folks are used to doing things on their own and often aren’t aware of the resources that are available,” said Matt Russell, Executive Director of the Alabama Fire College. “We went door to door to each of the 201 households that were impacted, identifying if they needed volunteers to help clear trees, or if they needed food, water, medicines or personal hygiene items.”

In one instance, firefighters came across a diabetic survivor who needed medicine immediately. Having the real-time link from the field to the EOC meant they could quickly route that request to the Medical Needs section to fill the prescription and get it out to that address quickly.

Sharing Perspectives on the Damage

An app-based approach also empowers first responders to gather reliable information to share with those impacted, giving them a big-picture understanding of the scale and scope of the event.

“These people are still trying to wrap their head around the fact that they’ve lost everything,” Busby said. “We need to get the information to the people so they can react and get the help they need.”

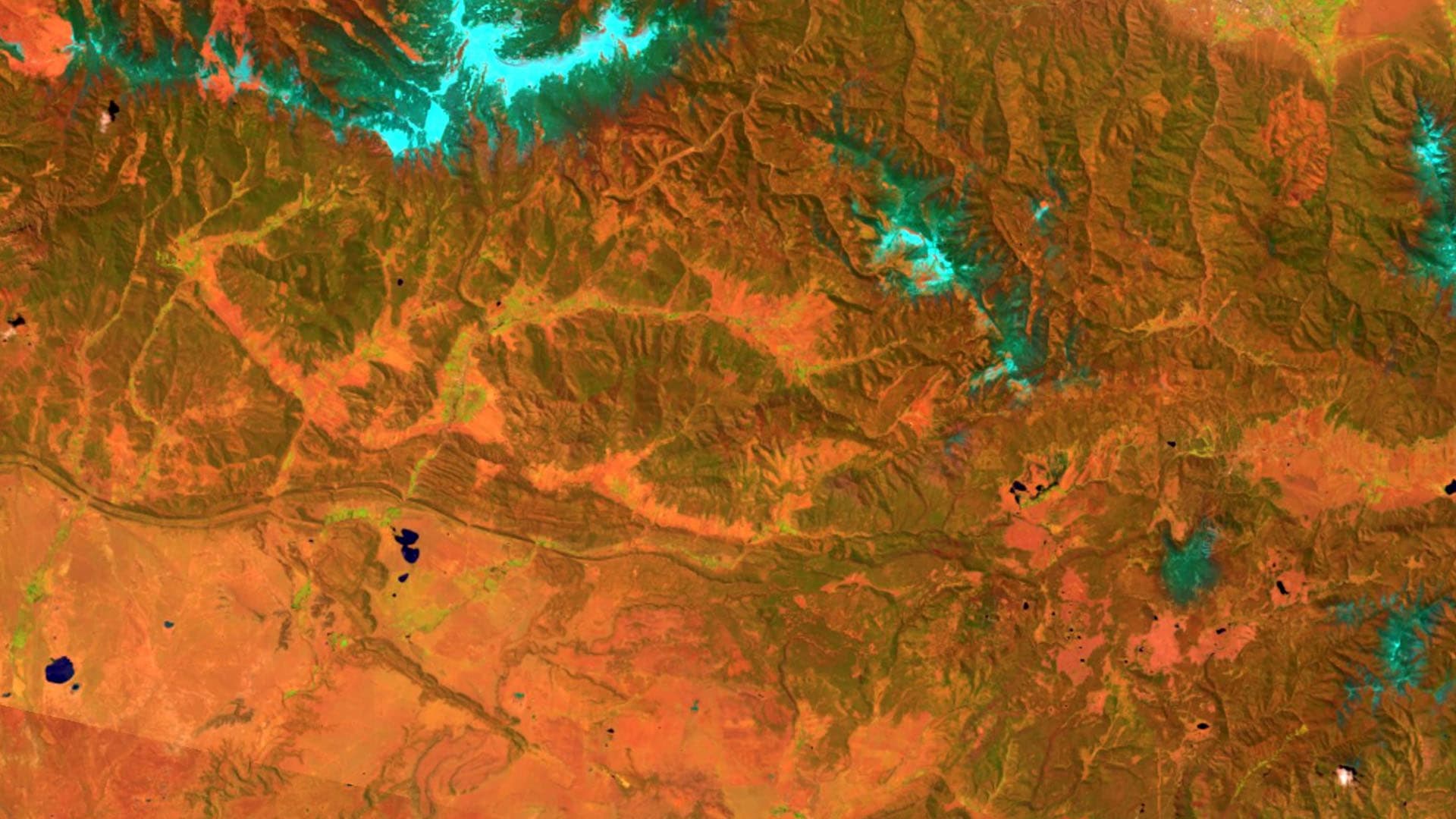

Aerial imagery from airplanes and drones provided a good deal of this information. Lee County had flown aerial imagery for the whole region within the past year. Along with after-tornado imagery, the before photos provided a good side-by-side comparison of the extent of damage. The National Insurance Crime Bureau’s Geospatial Intelligence Center(GIC) collected the first after-tornado aerial imagery in the wake of the event, and made that imagery available to first responders.

“The imagery of where the debris scattered helped us guide rescuers where to look,” Busby said.

The EOC uses field apps and the dashboard to help manage and coordinate field crews working on the response. From the first responders’ perspective, apps fill an information gap and help dispersed teams achieve more together.

“I happen to be on the Alabama Mutual Aid System Advisory Committee and I’m going to recommend this real-time capability as a primary objective of our search-and-rescue teams,” Russell said. “The more information we have upfront, the more efficient and effective we can be in the utilization of our resources.”

Though added efficiency is important, speed is not the primary objective.

“We have to make sure we allocate enough time to listen to the people,” Russell said. “We need to balance our interests of gathering information versus the mental health needs of victims who want to tell how they survived.”

Busby and his team focused on creating a conduit of details for those affected.

“I wanted to be sure I was answering any question I had the power to provide,” he said. “That stemmed from my aunts and uncles not having any details at their fingertips when they needed it.”

Once the response is over, the long path of recovery and rebuilding begins.

“Recovery is the longest lasting and most intensive activity, including mapping,” Busby said. “There’s now time to do more analysis and data mining in order to make informed decisions with all the right information in front of us.”

Esri’s Disaster Response Program provides software, data coordination, technical support, and other GIS assistance. Learn more about the Disaster Response Program or contact us in times of emergency.

All damage photos courtesy of Lee County.