GIS is a tool of discovery and imagination. Students go into data to tell a story, document history, and also reimagine what the community could look like from a more liberatory perspective.

February 15, 2024

We last spoke to Nick Okafor in 2021, about the successful Mapping Justice summer program for high school students taught through the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Introduction to Technology, Engineering, and Science (MITES) program. Okafor founded trubel&co to expand the program, taking it to southwest Florida via Florida Gulf Coast University and branching it into Michigan and Missouri. Okafor was recently named a National Geographic Explorer for this work.

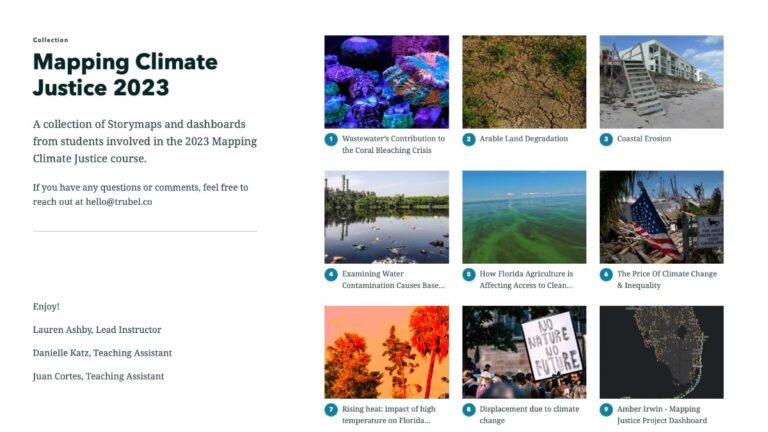

The Mapping Justice curriculum applies project-based learning and GIS technology for social change. Students have focused on issues that impact them, such as food deserts, the digital divide, gentrification, and disparities in city services.

Okafor provided an update on this work and spoke of overcoming new challenges in his quest to create good trouble, a term used by civil rights icon John Lewis to mean standing up for what you believe in.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Okafor: Mapping Justice acts as a gauge of what students in a region care about. It reflects the cares of the community in the problems the students want to solve. They make really incredible intersections and discoveries that, honestly, still blow my mind.

I am thinking about students from my first class back in 2020. One was interested in politics. One was interested in LGBT rights. We paired them together, and they researched transgender voter discrimination. They measured how many people this affects and were able to see that, in a lot of swing states, the amount of people disenfranchised—who couldn’t vote because of discriminatory voting policies—could have changed 2016 election outcomes. They showed real impacts to policy.

The students are solving with GIS and there are a lot of cool “uncoveries” they’re making. And the more we travel, the more good trouble we can spark in these communities. I’m really excited about the documenting and innovating that’s going to happen.

GIS is a tool of discovery and imagination. Students go into data to tell a story, document history, and also reimagine what the community could look like from a more liberatory perspective.

Okafor: It’s been an interesting place for a pilot project. I guess if we can make it work in Florida, we can make it work anywhere.

The opportunity came from the Esri Education Summit at Esri UC in 2022, where I gave a talk about how abolitionist principles could help GIS users create innovation around liberation. It connected with someone at Florida Gulf Coast University who wanted the course there.

It was a place to be! People had just gone through a hurricane, so the ability to focus on environmental justice was immediately relevant. They’re still rebuilding, and they continue to experience climate emergencies. It’s also a place where you’re not allowed to explore identity nor inequality through traditional education systems.

There’s a lot of need in Florida to have culturally responsive work that’s not just creating the space for civic discourse, but that melds technical upskilling in a way that’s inviting for women, people of color, people from different classes. GIS is an incredibly intuitive tool for young folks to explore their community while building data literacy.

Okafor: I’m at Stanford University pursuing a doctorate in management science and engineering. It’s a mix of business, technology, and sociology. I’m looking at the practice and pedagogy of what I’m labeling liberatory innovation—using data, design, and tech to advance ethics, equity, and justice. It builds on what I learned at Sidewalk Labs to use technology and services to make urban environments more affordable and sustainable.

I think education is going through a shift. We’re training new engineers, new computer scientists, new innovators. I want to make sure there’s a commitment to liberation that’s present from the moment they first learn how to code.

I want anyone who’s in this field of innovation—so that could be people making digital products, people creating new resources, people creating new strategies—to think through the impact of the work on society. And so, it’s twofold. One, are you aware of the potential to create good and do you know how all these cool tools you’re learning could be applied to help communities, to promote liberation? And two, are you aware of the ways these tools have created harm; the history of technological bias, of unethical data practices, of the ways that AI can actually target disadvantaged communities?

Okafor: It’s something that has continued since the abolition of slavery. A lot of ways it enters our work is in relation to the prison-industrial complex. We think about abolition in terms of taking down the systems that are entrapping people in carceral systems. A lot of great scholars are using liberation and abolition frameworks to advance what’s possible.

The beauty about abolition is the creative potential and how it is so aligned to the ways we innovate. Mariame Kaba describes abolition as an analysis of the drivers of oppression, a political vision, and a practical organizing strategy. Put simply, you’re looking at the past to see what harm has been caused. You’re thinking forward to the future to see what good we can create. Then you’re acknowledging and repairing that harm and working toward a liberatory future.

Our job within Mapping Justice is that organizing strategy. We say that you can use data, design, and technology to document that past and reimagine your future. Let’s put it on a map. Let’s really engage and start to problem-solve in real time.

Okafor: Nat Geo was a key part of my childhood, giving me a window to explore stories of the world. With this funding, I’m honored to be bringing the power of geospatial storytelling—backed by liberatory innovation—to Saint Louis, the community that first shaped my own views of good trouble.

Learn more about governments, nonprofit organizations, and businesses apply GIS to advance racial equity; social justice; and sustainable, inclusive development.

September 19, 2023 |

December 21, 2021 | Multiple Authors |

August 16, 2017 |