When Kendall Cotton walked into Montana legislative committee meetings in early 2023, he carried two zoning maps—side by side. One showed Missoula, Montana, a mountain city of 78,000 people known for outdoor recreation and its university. The other showed Los Angeles.

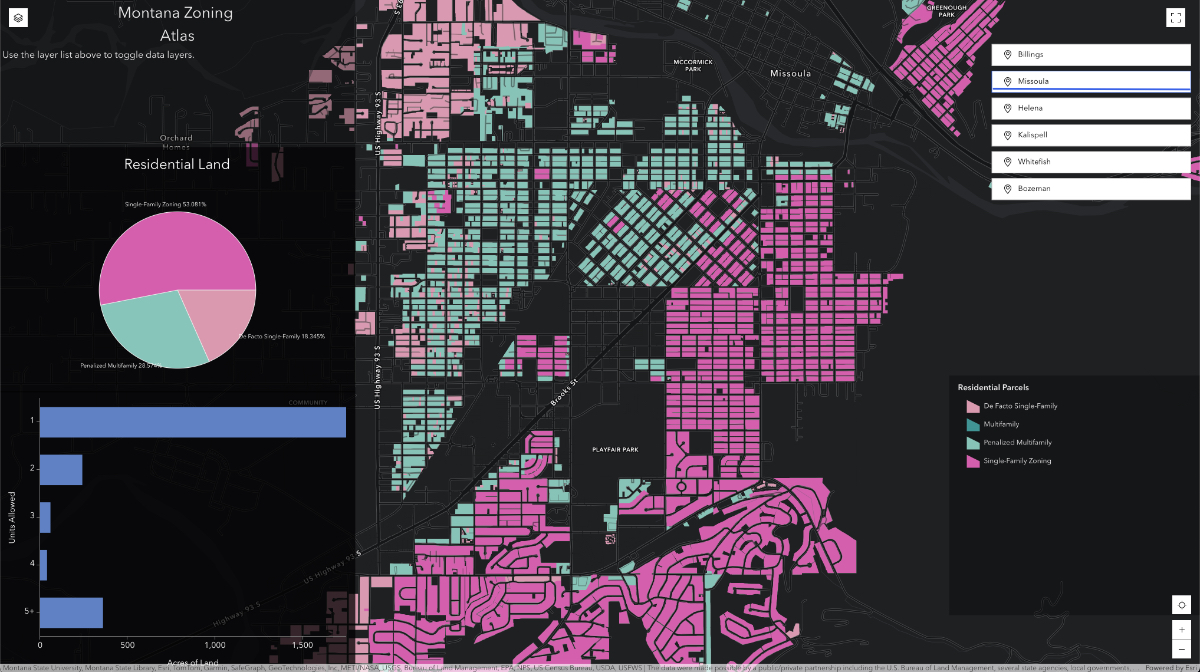

The maps were nearly identical. In both cities, roughly 75 percent of residential land was reserved exclusively for single-family homes, prohibiting the duplexes, triplexes, and “missing middle” housing that working families could afford.

For Montana legislators, the visual clarified a fear building since the pandemic: their small, fast-growing cities were following the same restrictive zoning patterns as major metros. “If this city is zoned like LA, it’s going to grow like LA,” Cotton told lawmakers. “I don’t think a single Montanan wants that.”

That comparison became a catalyst for what housing advocates call the Montana Miracle—bipartisan housing reforms that passed in 2023. The laws legalize duplexes, require cities to allow accessory dwelling units (ADUs), open commercial zones to mixed-use development, and restructure how housing gets approved statewide.

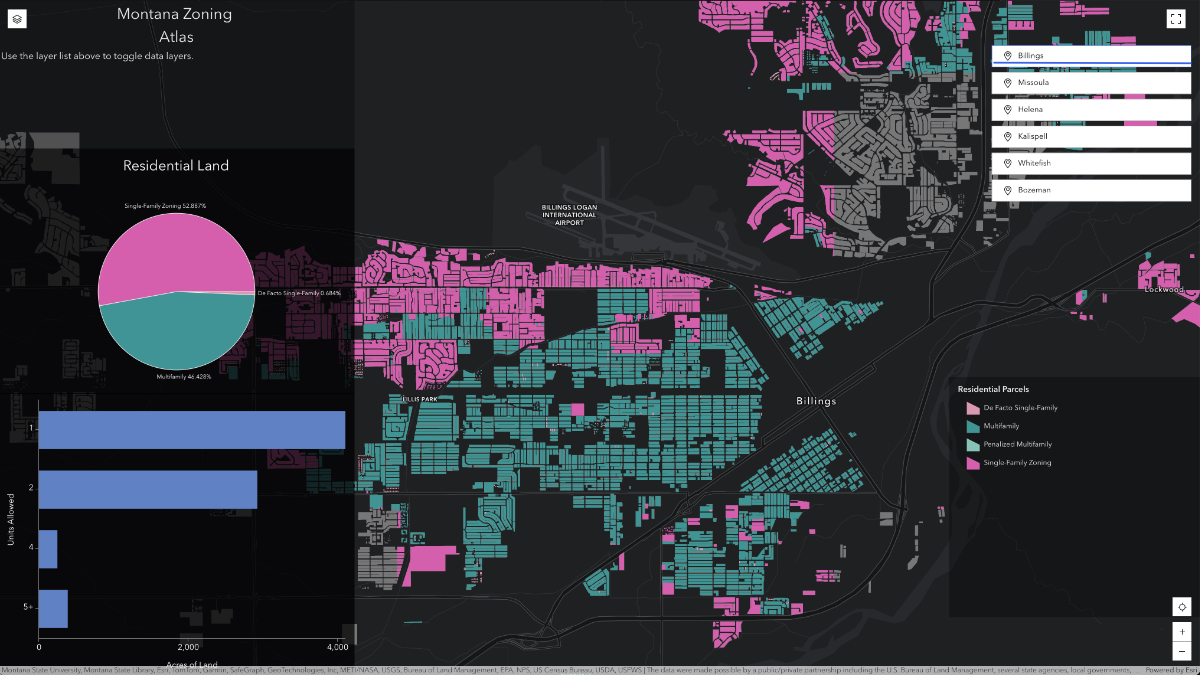

Cotton is president and CEO of the Frontier Institute, a free-market think tank in Helena. His team created the Montana Zoning Atlas to help officials and the public visualize the state’s housing data. Built with geographic information system (GIS) technology, the atlas transformed abstract zoning regulations into something anyone could immediately understand. And it helped fuel remarkable reforms.

Making the Invisible Visible

Montana had become one of the hottest housing markets in America. Remote workers discovered its snow-capped mountains and glistening rivers during the pandemic and relocated, creating unprecedented demand. Home prices in Bozeman hit a median of $900,000. Long-time residents were being priced out and forced to move farther from where they worked, creating the kind of sprawl that Montanans had always associated with places like California.

State and local leaders were spending money on subsidized housing programs, but the crisis kept getting worse. Cotton’s team suspected that local zoning regulations were a major culprit, but there wasn’t data to prove it. “There was a lot of skepticism around regulatory reform as a viable strategy,” he said.

Cotton had no formal training in GIS when his team started working on the atlas. But he knew lawmakers would respond better to maps than spreadsheets.

-

Governor Gianforte announces Montana's bipartisan housing reforms alongside an unlikely coalition—a developer, Kendall Cotton from the Frontier Institute, and city councilors from both parties.

The Power of Parcel-Level Mapping

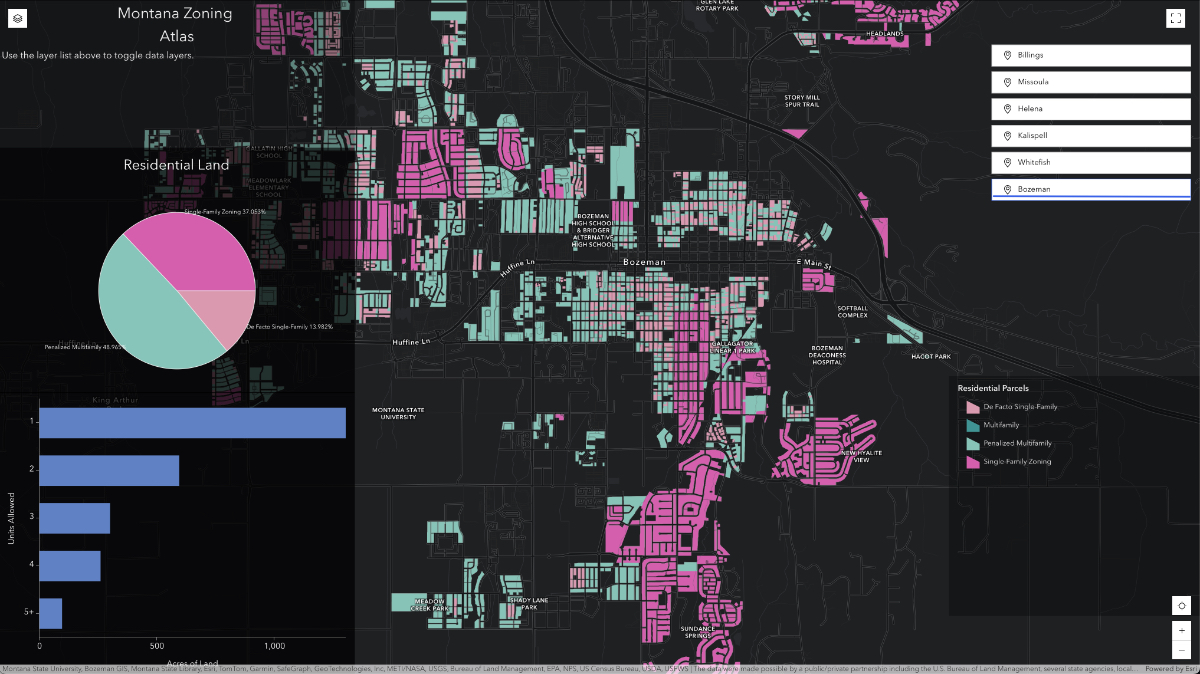

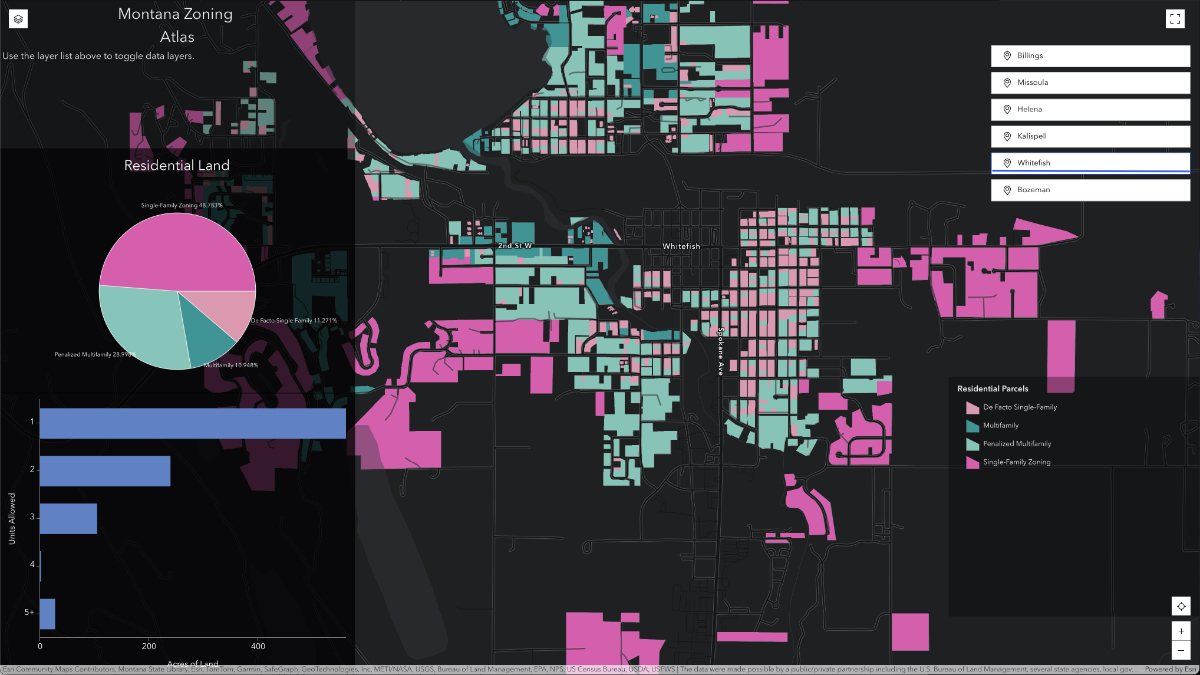

The Montana Zoning Atlas showed most Montanans something they’d never seen: a clear, color-coded picture of exactly where housing can and can’t be built in their communities. The interactive map allows anyone—legislators, developers, activists, or curious homeowners—to zoom in on their neighborhood and understand the regulations that shape it.

The atlas revealed patterns statistics alone couldn’t capture. Bozeman was hit hardest, where 55 percent of residents are renters—many spending over 30 percent of their monthly income on housing costs. The city appeared to allow duplexes and triplexes in certain zones, but parcel-level analysis told a different story. Factoring in minimum lot size requirements, the Frontier Institute found areas where lot size requirements exceeded the space that already exists.

The team coined a term for this: “de facto single-family zoning.” Even in zones technically allowing duplexes, the underlying regulations made them impossible to build.

City-specific profiles also enabled powerful comparisons. Helena, Montana’s capital, had voluntarily eliminated minimum lot sizes in 2019, and remained significantly more affordable than Bozeman and Missoula. These comparisons proved valuable for Montana’s part-time legislature of farmers and ranchers, many from counties without any zoning at all.

Within weeks of the atlas’s publication, Montana’s five youngest state lawmakers wrote an op-ed calling for reform. When Governor Greg Gianforte convened a housing task force, the group incorporated visualizations from the atlas into official reports, which formed the basis for the 2023 legislative reforms.

-

The Montana Zoning Atlas interface for Billings shows a more balanced zoning pattern, with roughly half of residential land allowing multifamily housing (teal) versus single-family (pink).

An Unlikely Coalition Spurs Unprecedented Progress

When Governor Gianforte held a press conference to promote the housing reforms, those standing beside him told a unique story: a developer, Cotton, and two city councilors from opposite sides of the political aisle.

The diversity was deliberate. When the Frontier Institute rolled out the atlas, they highlighted different perspectives—climate advocates concerned about sprawl, developers sharing their challenges, homeowners and renters, and the Frontier Institute’s own property rights message.

“There are a lot of different ways to address this issue, and we’re not saying any one is right or wrong,” Cotton said. “At least we can all agree that there’s a big problem here and we need to address it.”

The objective data gave disparate groups a common language. Transportation advocates, renter advocacy organizations, and free-market policy groups—people who typically don’t work together—found themselves united by what the maps revealed.

That coalition powered an extraordinary legislative session. In 2023, Montana passed four major housing reform bills with broad bipartisan support. Senate Bill 323 legalized duplexes in cities over 5,000, and prohibited penalizing duplex construction compared to single-family homes. Senate Bill 528 required cities to allow ADUs and eliminated barriers like owner-occupancy requirements and parking mandates. Senate Bill 245 restored property owners’ rights to build mixed-use and multifamily developments in commercial zones.

The most transformative legislation was Senate Bill 382, which restructured Montana’s land use planning process. The bill had been in development for years by planners and local governments. “Our zoning atlas pushed this conversation forward with lawmakers and actually crystallized the housing issue,” Cotton said.

Cities must now set specific targets for housing production for the next 20 years, and their zoning maps must accommodate that growth. Most significantly, the bill moves public hearings to the planning phase. Once growth plans and zoning maps are established, individual housing projects that receive administrative approval skip discretionary public hearings, resulting in faster construction.

The bill passed nearly unanimously.

The impact is already visible. Missoula, the city that Cotton had compared to Los Angeles, has updated its zoning map under the new process. Real estate listings now advertise land with the selling point that it can be developed with middle-density housing, not just single-family homes.

Cotton expects housing production to accelerate significantly once all cities finalize their new land use plans by May 2026.

-

Multi-story housing construction in Missoula represents the kind of middle-density development that Montana's 2023 reforms made easier to build after decades of restriction.

Setting an Example for Mapping Housing Data

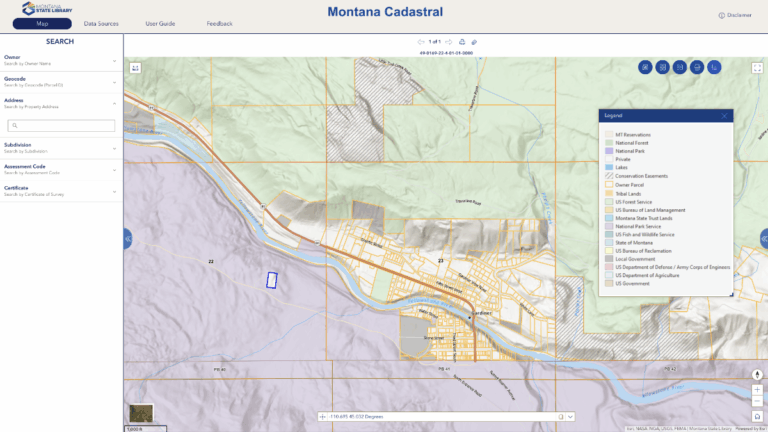

What surprised Cotton most throughout the project was the difficulty in accessing zoning data. He expected standardized information on city or county websites. Instead, he made phone calls and received faxed PDFs of zoning maps. Some cities didn’t have GIS files at all—the Frontier Institute had to create digital maps from paper maps for several municipalities.

For other communities considering similar projects, Cotton’s advice is straightforward: don’t reinvent the wheel. “Reach out to the National Zoning Atlas and lean on their methodology and resources,” he said. The standardized approach means even those without GIS backgrounds can contribute.

The Frontier Institute’s data is all open source. Spreadsheets of zoning regulations and shapefiles are available for download on their website. “We want to collaborate with anybody and everybody who wants to help expand this project,” Cotton said. He envisions researchers, or even state and local governments themselves, building on the foundation they created.

The Next Frontier

As Montana cities finalize new land use plans, Cotton sees a broader opportunity to make zoning atlases a permanent public service rather than one-time research projects.

“I’ve encouraged our state folks to consider having a state of Montana-hosted zoning atlas and curating that data,” he said. Such a resource would let developers quickly understand different jurisdictions and let residents verify rules for themselves rather than relying solely on local planners or officials.

The Frontier Institute is shifting its focus to a broader property rights conversation. “We’re starting to zoom out and look at where local land use regulation is preventing home-based businesses from being started in residential neighborhoods,” Cotton said.

Montana’s housing reforms stand as proof of what’s possible when complex regulations are made easily understandable. A small team with limited resources created maps that influenced laws, unlocked thousands of housing units; and demonstrated that when people can clearly see the problem, reform becomes inevitable.

Learn how to use GIS to develop an effective housing strategy.

Related articles

-

March 18, 2025 |

March 18, 2025 |Keith Cooke |Urban Planning -

July 10, 2025 |

July 10, 2025 |Patricia Cummens |Infrastructure Western Governors Map Ways Out of the Housing Crisis with GIS Technology

-

May 6, 2025 |

May 6, 2025 |Geoff Wade |Natural Resources RoyOMartin’s High-Tech Forestry Approach Poised to Meet America’s Housing Crisis