August 30, 2017 |

January 11, 2018

Community Converts Vacant Properties into Revenue Opportunities

What does a city do when it discovers the largest owner of its blighted properties is… the city itself?

The city of New Bern, North Carolina sits on the coast at the confluence of the Trent and Neuse rivers, a prime spot that made it the state’s second colonial settlement in 1710. The area thrived on lumber trade until the 1920s. Manufacturing of appliances and plumbing fixtures now provide the bulk of employment for the city’s 30,000 citizens, but the sector has contracted.

In 2014, the city received a grant from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development to plan the revitalization of a blighted low-income area. The planning process that followed helped the city uncover a disturbing pattern. When highlighted on a color-coded map of public and private land owners, the overwhelming majority of abandoned parcels jumped out as being city or county owned. The city, it turned out, was the “bad landlord” responsible for the blight weighing down this low-income community.

The city hadn’t purchased the land. It had come onto the books from tax defaults, foreclosures, donations, refused estate transfers, and other forms of home and land abandonment. In all, the city held a portfolio of more than 200 properties. An audit revealed that each year, the city was spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on maintenance and missing out on $2.4 million in potential property tax revenue.

Taking Stock

The city hadn’t created the disagreeable conditions of the properties, but it had become the legal caretaker. As expenses mounted, New Bern decided to put the homes and vacant lots on the market.

“The city’s not in the real estate business, and it’s not a developer,” Alice Wilson, GIS coordinator for New Bern Development Services, said. “We’re in the business of guiding development and trying to help this area rebound.”

The city focused their efforts on a strategic plan to achieve the three stated goals of revitalization of the Choice Neighborhoods Implementation grant it received from HUD:

In this entire process, the city expanded the use of their geographic information system (GIS) from a system of record to a system of insight, and ultimately to a system of engagement. The city’s GIS held the property records central to this planning effort. It helped the city and its citizens understand the interconnected nature of housing, poverty, and neighborhood decline through insights uncovered by an analytical process known as spatial analysis. GIS also provided the means to take action through citizen engagement in the planning process, populating an interactive map for the sale of properties, and communicating progress on the turnaround.

Taking Charge

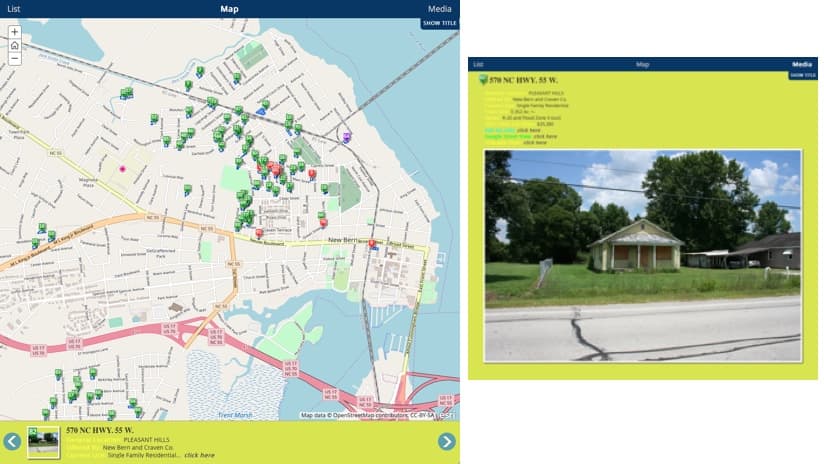

The city took photographs of each property, gathered information about each home and parcel, linked each record to the online portal of historic tax records, and created a GIS-based Story Map to present the properties to the public.

Not all of the 200 properties went on sale. The city analyzed land use and set aside land best suited for utilities or municipal projects. Habitat for Humanity was given eight of the parcels to develop new homes. Additional parcels were dedicated for community gardens built by local veterans. And small lots that were unsuitable for construction were earmarked for charitable causes.

Of the 150 properties that the city intended to sell, it began slowly, putting 20 properties on the market to see if they would sell. The local newspaper ran an article on the plan. Immediately, the city received a bevy of calls asking for a list of all available properties. During those early days of the sale, the property website received 100 daily views. That has grown to more than 500 today, as the city continues to draw down its inventory and prospective buyers hover, waiting for new properties to be released.

“We learned some valuable lessons when we first put the properties out there,” Wilson said. “We had some people offer us just a dollar. So, we had to set some rules and regulations on how we would sell the property.”

While individual parcel sales don’t yield the city much in the way of immediate revenue—often under $10,000 per transaction—their cumulative impact is significant.

Since late 2015, New Bern has achieved more than 45 abandoned-parcel sales. The city has awarded 17 permits for new homes, with eight homes built and occupied to date. While not a large figure, it equates to a significant reduction in derelict property inventory, $1.1 million in propery sales and permit proceeds, and increasing tax revenues thanks to new ownership and the increasing value of neighboring properties.

Revitalizing a Community

The benefits of New Bern’s vacant land sales have expanded beyond the revenue they generate. In line with HUD’s goals, the city has advanced the quality of housing, addressed educational outcomes, and created conditions for further investments in the neighborhood.

In the search for a job training site in the area, the city took another look at an old electric generation plant and warehouse that had been vacant for some years. The city secured a US Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration grant for renovation, and partnered with the local community college to stand up a regional workforce development and training center. The center will host classes, offer hands-on training, and trade certificates. The curriculum includes small engine repair, construction trades, manufacturing, and food service.

Another example of community redevelopment stemmed directly from the city’s distressed-property sale. A local businessman purchased one of the first properties New Bern put on the market, a commercial building that he’s working to convert into rental apartments. With a homeless shelter just a block away, he hopes to provide low-cost housing near both the shelter and the training center to provide a bridge for homeless people to help themselves get back on their feet.

In addition, the city worked with a local church and veterans group to create two community gardens to be maintained by handicapped veterans. The veterans will grow, sell, and give vegetables to the surrounding neighborhood, providing fresh produce in an area commonly referred to as a food desert, where no grocery stores exist.

The initiative to sell city-held lots has also triggered a resurgence of communal pride, breathing life into the city’s historic residential core. The city developed a program called Paint Your Heart Out, hiring college students in the summer months to help paint, fix up, and repair houses whose residents couldn’t handle the upkeep—physically or financially.

“The majority of the repair requests have been close to the properties that we’re selling,” Wilson said. “The correlation between rebuilding efforts and people taking better care of their properties is clear to see.”

New Bern’s community revitalization effort earned acknowledgment from the Urban and Regional Information Systems Association (URISA), a nonprofit association of professionals using GIS to solve government challenges. URISA recognized the city’s abandoned property sale system as a Distinguished Single Process System in their 2017 Exemplary Systems in Government Awards. URISA commended New Bern for its creative application of information system technology to automate vacant parcel sales, resulting in improved government services.

“The use of story maps for the property sales project was a lot easier than I thought,” Wilson said. “The success has given me encouragement and a desire to do more, and to share and help other departments fully utilize GIS.”

Learn how the power of location intelligence helps create smart communities. A collection of maps and apps help cities understand current property conditions, return blighted properties to productive use, and engage the public in conversations that stabilize neighborhoods.

August 30, 2017 |

August 28, 2017 |

October 31, 2017 |