October 1, 2019 |

January 15, 2020

The region of Bangladesh near the Bay of Bengal known as Cox’s Bazar poses an unlikely candidate for a spontaneous metropolis. The country has the second-highest rate of disasters in Asia and the Pacific with conditions that include heavy monsoon rains, flooding, and landslides. Because of its coastal location, Cox’s Bazar also endures cyclones.

Yet, since 1991 Cox’s Bazar has been a refuge for the Rohingya people fleeing neighboring Myanmar. As a Muslim minority group in a predominantly Buddhist country, the Rohingya have endured decades of ethnic and religious persecution.

In August 2017, Burmese security forces launched massive attacks on predominantly Rohingya areas of Myanmar. In one of the largest forced migrations in modern history, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya left their homes on foot and crossed the border to Bangladesh. Many made their way to the Kutupalong Balukhali camp.

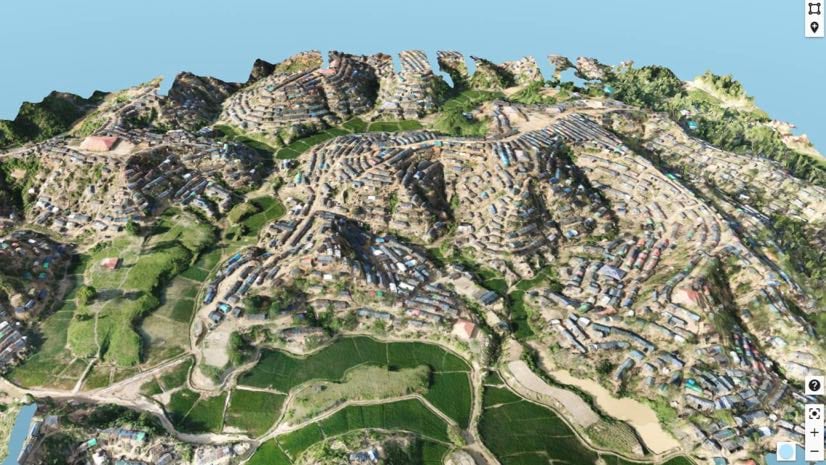

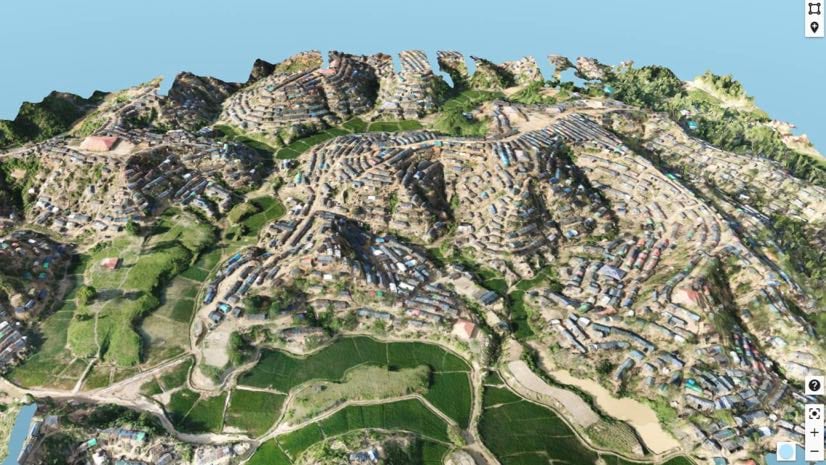

Prior to the influx, Kutupalong Balukhali and camps in Teknaf housed around 200,000 people. Within weeks, the population ballooned to 500,000. It quickly became one of the world’s most densely packed refugee camps in a resource-scarce country that already has some of the world’s densest living conditions.

The population increase created enormous logistical challenges for the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which works with the Bangladeshi government and UNHCR to administer the camps. In particular, IOM staff are challenged in the region’s rainy season that spans the months of June through September. Nearly one-third of the camp—including one-quarter of its latrines and nearly half of its hand pumps for water—is at risk for flooding and landslides. Heavier rainfall also correlates with increased health risks.

Using Drones to Map the Unmappable

The overarching need for workers at IOM and in the Bangladeshi government was to visualize the camp’s extent. Getting a sense of how—and how many—people were transforming Kutuapalong could help answer questions about how to accommodate them. City planners require maps with detailed information about land, population, and infrastructure. The new Kutupalong Balukhali was a cartographic blank slate.

“When I was deployed in September, there was no clear visual representation of the extent of the camp,” said Sebastian Ancavil, international mission and geographic information system officer at IOM. “We were in the dark, because even a month after the exodus, nobody had good information about the situation. That’s why we requested to have a drone fly over it.”

Unmanned aerial vehicles—commonly known as drones—are used for many situations that require aerial surveilling, from forest fires to power lines. For the Kutupalong Balukhali project, a drone alone proved insufficient. Doing the job right would require additional technology.

Ancavil’s professional specialty is geographic information systems (GIS) software that organizes geographically-specific data onto digital maps. For Ancavil and his team, a drone with GIS capabilities provided the first comprehensive view of Kutupalong Balukhali’s ongoing transformation.

Before drones became a viable option, Ancavil employed GIS for similar purposes. After a devastating earthquake hit Haiti in 2010, he used satellite imagery to monitor rebuilding efforts in Port-au-Prince. The accelerated pace of this rebuilding meant that the imagery was often outdated before it became available.

Although GIS technology was more limited at that time, Port-au-Prince was an established urban area with preexisting maps that provided a baseline of information to assess earthquake damage. Kutupalong Balukhali presented the opposite challenge as no maps existed of the quickly created community. Haiti provided the laboratory to create the drone mapping approach. “In Haiti, we went from nothing to something,” Ancavil said of the technological innovations to create up-to-date maps. “For Bangladesh, the technology and methodology were there, but there were no existing maps.”

Making Drones Smart

Mapping Kutupalong Balukhali involved a third technology, artificial intelligence (AI), to augment GIS data. The addition of AI gives today’s GIS the ability to automatically and quickly process complex imagery. The drone imagery—combined with map data from OpenStreetMap and other partners—could be programmed to recognize and categorize geographic features, including buildings, human-made objects, vegetation, and soil. (To alleviate privacy concerns, the drone is flown at an altitude too high to capture recognizable images of individuals.)

These rich images give Kutupalong Balukhali camp administrators a comprehensive view of the area’s ad hoc structure. Kutupalong Balukhali is subdivided into 23 smaller camps, each containing around 1,500 blocks, with around 100 families per block. Every block has a community leader who represents the block and communicates its needs, including food, education, and security.

This information becomes part of the GIS database, along with a community leader’s rough population count, which lets relief workers visualize the density of a block. “We draw small polygons on the map so that it’s easier for a community leader to give information that helps our field team assess the block,” Ancavil said.

Capturing a Changing Landscape

The combination of drone imagery, GIS, and AI also helps workers understand the land the camp occupies. An influx this large involves massive environmental upheaval. Thousands who fled with nearly nothing were forced to grab bamboo and other materials for shelter, causing deforestation that exacerbates existing environmental challenges. The camp expansion even impacted elephant migration routes, yet another danger camp residents face.

“We can remove all the human construction from the map,” Ancavil explained. “Then you’re left with just the ground surface, which lets us provide a digital terrain model to partners who calculate landslide risk and flood modeling.”

Besides mapping the camp and helping site planning and development, the use of GIS for Kutupalong Balukhali provides a platform for a broad range of data about people and place pertaining to the camp. With mobile devices, relief workers from UNICEF and other agencies, can access various cloud-based datasets. “We are a data provider,” Ancavil explained. “We share the information with our partners, through the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) platform for example, and they can take whatever they need to do their work.”

The estimated population of Kutupalong Balukhali and satellite camps that have formed around, including those in Teknaf, now hovers around 900,000. As ongoing drone flights provide bird’s-eye-views of the camp, the new data provides ground-level context. The result is a living document that evolves with the camp.

The drone also had the unexpected effect of providing an outlet for childhood fascination. “I had a group of kids follow me on the first mission,” Ancavil said. “I didn’t understand them, and they didn’t understand me, but they stayed with me all day.”

Learn more about how location intelligence focuses and prioritizes relief missions.

View the story map below from UNHCR for more details and context about the Rohingya refugee camps.

October 1, 2019 |

August 6, 2019 |

September 27, 2017 |