August 28, 2025

Fire Chief Scott Olsen can’t stop thinking about Hurricane Katrina. In 2005, as a planning section chief on FEMA’s Urban Search and Rescue Incident Support Team, he found himself in a Sam’s Club parking lot in Jefferson Parish, right next to New Orleans where nearly everything was flooded, searching for maps of the city’s streets. “We ended up getting a bunch of spiral bound New Orleans street guides and tore them all apart and taped them up—that’s how we created our division assignments,” he said.

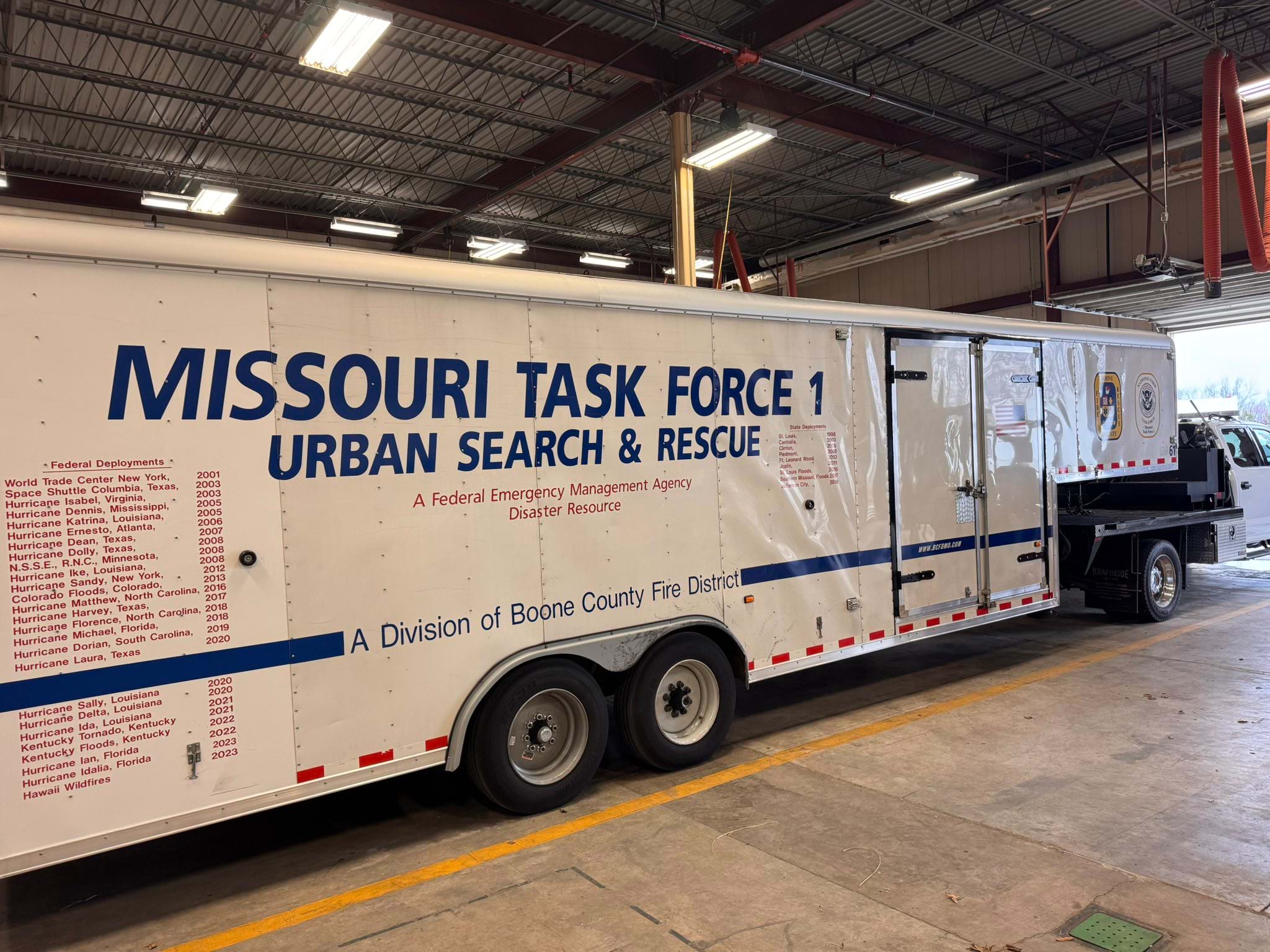

It was chaos. Teams searched the same flooded neighborhoods multiple times while missing others. People were later rescued in areas responders thought they had cleared. That experience made Olsen, now leading the Boone County Fire Protection District and Missouri Task Force 1, passionate about maps, drones, and other situational awareness tools to guide rescue teams.

Twenty years after Katrina, Olsen’s Missouri Task Force 1 is testing revolutionary approaches to disaster response. They work inside Guardian Centers—an 830-acre training facility in Georgia that looks like a disaster movie set. Built by first responders for first responders, the facility provides realistic post-disaster environments (see sidebar) where teams can test technology, build coordination skills, and learn from past failures.

This year, they tested drones and the latest version of the Search and Rescue Common Operating Platform (SARCOP) that is built on geographic information system (GIS) technology with funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Department of Homeland Security, Science and Technology Directorate. The exercise wasn’t about brute force—breaking through walls or removing rubble. It was about precision mapping and a level of situational awareness that turns chaos into coordinated action.

While many first responders still debate whether to add drones to their operations, the Boone County Fire Protection District and Missouri Task Force 1 make drones central to their strategy.

“The most difficult things for us to determine is what’s the scope of the disaster,” Olsen said. “The drones are able to give us a very quick visual.”

Jason Warzinik, IT/GIS division director for the Boone County Fire Protection District, leads the Disaster Situational Assessment and Reconnaissance (DSAR) team—a specialized unit that puts drones in the air as one of the first steps of any disaster response.

The DSAR team operates with certified drone pilots, GIS specialists, data analysts, and communications experts. They deploy incident command vehicles equipped with ruggedized tablet computers, satellite internet connectivity, and large-format printers. Their drones help conduct reconnaissance missions—including looking for survivors—to direct ground crews to where they’re needed most.

During this year’s Guardian Centers exercise, the DSAR team used drones to quickly perform tasks too dangerous for humans. They flew aircraft through collapsed buildings filled with simulated hazardous materials.

“We can send a drone in and at least know what hazards we might encounter and how many people we’re dealing with inside that need to be rescued,” Warzinik said.

Thermal cameras affixed to the drones help locate victims through debris while specialized sensors detect dangerous gases. Live video streams let incident command assess conditions and supervise as teams on the ground navigate treacherous terrain.

The difference between twenty years ago and today is striking. During Katrina, rescue operations relied on paper maps, with teams marking progress by hand and often following haphazard search patterns. This evolved to the use of GPS units to document search progress until as recently as 2018, however, this was still a relatively inefficient process and did not provide real-time situational awareness.

Now, SARCOP creates a shared map showing exactly where every team has searched, what they have found, and which areas still need attention. Used nationwide at the local, state, and federal levels, the software is developed and maintained by the National Alliance for Public Safety GIS (NAPSG) Foundation, in close coordination with FEMA.

During Hurricanes Helene and Milton in fall 2024, over 100 response teams coordinated through SARCOP, documenting 246,756 damage observations and 18,274 resident interactions across six states.

The real power comes from integration. Drone imagery, aerial photos, and incident situational awareness information flows directly into SARCOP, in real time. When a drone spots a potential survivor in need of assistance, the location appears instantly on every rescuer’s map. When structural specialists identify dangerous areas, those hazards get marked for all teams to see.

Jared Doke, director at NAPSG Foundation, explained how drones have changed the way teams make critical decisions. “For example, you’re taking a boat down a river for a water rescue, and you get to a flooded area where there’s a fork in the river. Do you go left, or do you go right? You can pop a drone up and send it ahead to know if you can get below a bridge or if there’s a blockage.”

In Georgia this year, teams tested SARCOP version 10, which introduces a new concept called “work sites”—areas requiring sustained attention from multiple specialist teams. These are locations where, as Doke explained, “they’ll send a drone team in first, then they bring in structures specialists to assess the safety of the building, then a rescue squad may shore it up, and then once it’s shored, they bring a canine team in to search for people.”

This sequential approach ensures the most impacted locations get the most thorough attention, with each team building on the work of those who came before.

Training at Guardian Centers extends to the next generation of emergency responders. DSAR small unmanned aerial system (sUAS) pilot and GIS specialist Chad Sperry, director of the Western Illinois University GIS Center, brought students there. “The opportunities that they get are just phenomenal,” Sperry said about the hands-on experience. For Sperry, this isn’t about technical training—it’s about sharing the camaraderie of the responder community and preparing students for the fast pace and accuracy required when lives are at stake.

Using SARCOP, teams do more than coordinate current disaster operations—they build knowledge for the future. Archived data helps them understand search patterns and improve response times. “We can look at our resources we had in past incidents, how long it took us, and then use those metrics for the next hurricane,” Doke said. This direct feedback also helps NAPSG Foundation to improve future versions of SARCOP, based on real-world experiences and lessons learned.

This evidence-based approach helps answer critical questions: How quickly can teams search disaster-damaged neighborhoods? How many buildings can they check per hour? What resources will the next disaster require?

The most promising developments combine and integrate a variety of tools and perspectives.

As Warzinik noted, “We’re using ArcGIS Survey123 forms for safety checklists, ArcGIS Field Maps, SARCOP, and a lot of GIS technology for managing drone data and these valuable images and videos.”

The integration of leading technologies creates new capabilities. Teams share a common operating platform that transforms disaster zones from chaotic scenes into mapped, measured environments where real data informs every decision.

The result? Faster, more effective responses. Safer operations. More thorough searches. And ultimately, more lives saved.

In a world where disasters seem increasingly common, this coordinated approach offers something invaluable. It gives responders the accuracy and shared awareness they need. That’s a far cry from tearing apart gazetteers in a parking lot in New Orleans surrounded by flood waters.

Learn more about how emergency managers use GIS to better prepare for and respond to disasters, and how Esri’s Disaster Response Program offers assistance to communities.