Luiz Marchiori stepped outside his apartment building in Porto Alegre one Sunday morning in May 2024, squinting into the bright sunshine. There was no sign of what was to come—of the fierce floods that would soon strike his Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul.

“I walked through the center of the city, and it was calm. But the water was rising,” said Marchiori, a meteorologist-turned-founder and CEO of Codex—a company specializing in the most advanced geographic information system (GIS) technology often used to prepare for and respond to this type of natural disaster.

Two hundred miles north in the highlands, a year’s worth of rain had fallen in just three days. Water was racing through every river and stream toward Marchiori’s city—the state capital and regional home to 2.3 million people—carrying with it a force that would challenge everything he thought he knew about extreme weather.

Marchiori’s mind was racing as he thought of how to help and the data that would be needed. He knew GIS dashboards could give responders real-time awareness of the locations and conditions of people and resources. He considered how GIS maps could become lifelines for residents who would need to find shelter and food. He anticipated that people and goods would need to be routed around broken roads and bridges. He expected calls from Codex’s government customers to help them see clearly amidst the chaos.

What he didn’t know was how many of his small team of technologists would be displaced. When they lost everything, his office and their GIS skills would sustain and distract them from the anguish, while giving them purpose in their darkest hour. They would work day and night, building real-time mapping apps to support rescue and response.

Statistically, such an event was supposed to occur once every 10,000 years. Even Marchiori, with his meteorological background, had never studied situations this extreme.

“There was never a scenario that could predict what happened,” he said. “Everyone who works with these scenarios needs to rethink everything.”

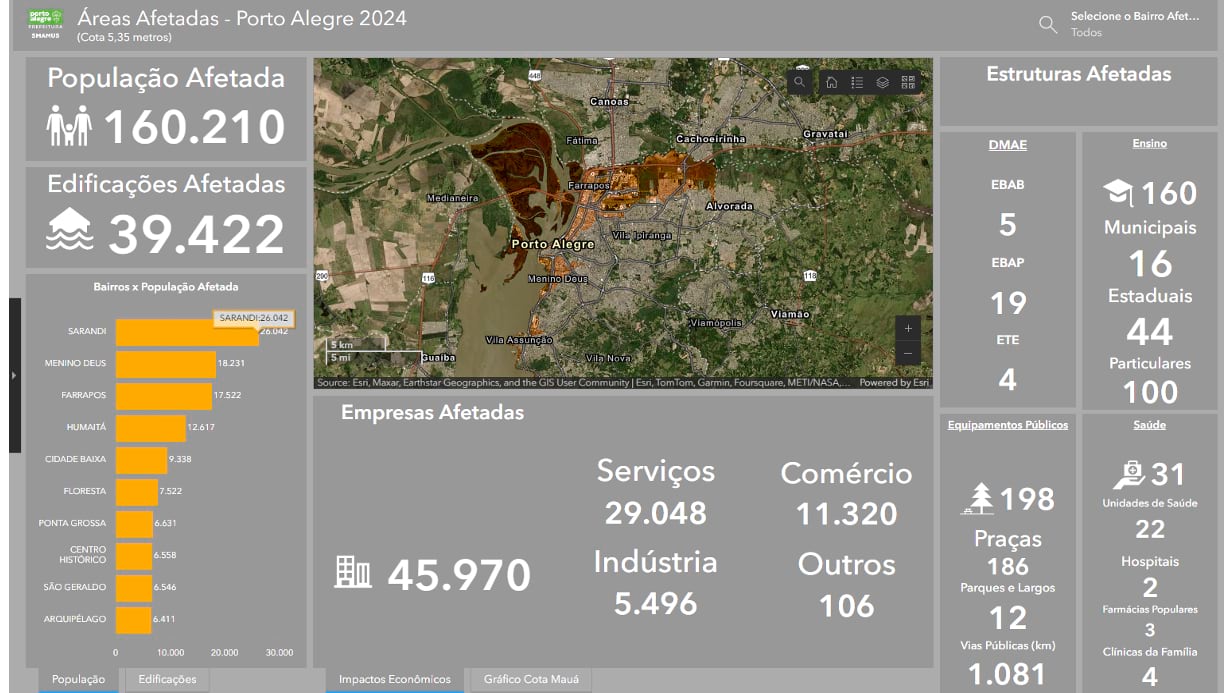

The geography of Rio Grande do Sul concentrated the power of the extreme rainfall. All the water from the highlands funneled toward the same place—the Porto Alegre region. Then, in a cruel twist of meteorology, south winds pushed brewing storm clouds against the highlands, bringing more rain as atmospheric pressure from the ongoing heatwave blocked the clouds’ natural path to the ocean. A floodwater volume of 1.5 billion cubic meters descended on the city, causing water levels to rise at unprecedented speed and displacing 600,000 people.

Within 48 hours, rushing waters overwhelmed the city’s Dutch-inspired pumping system—designed to manage water in a region that sits below sea level. The pumps that normally push excess water into the ocean were knocked offline by inundated electrical systems. Water levels in downtown Porto Alegre reached nearly seven feet. The airport, 70 percent under water, would remain closed for six months.

For Marchiori and Codex’s 70-person staff, the disaster was deeply personal. Four employees lost everything. Twelve had to evacuate their homes. Those who could make it to company headquarters brought mattresses and stayed for the duration of the event. The office never lost power or internet connection, so it became both an impromptu shelter for displaced staff and an emergency operation center to deal with the flooding event.

“When this kind of disaster happens in Brazil, it usually affects people with lower income, more vulnerable people,” Marchiori said. “But in this case, it happened to everyone. People with mansions, people with shacks—everyone was affected. It was a really democratic disaster.”

As the waters rose, traditional systems collapsed. The state’s entire data infrastructure, located in low-lying areas, completely flooded. Government officials found themselves unable to access maps, databases, or even basic information about water levels. Bank systems went down for three days. People couldn’t buy necessities because electronic payment systems had failed.

Codex received immediate aid from its business partner, Esri, through Esri’s disaster response program. Codex offered its services to Brazilian state and local governments free of charge. “We put ourselves in a position to help,” Marchiori said. “We just said, let us do what we can.”

Government officials set up emergency headquarters on higher ground and gave Codex a workspace. The team worked around the clock, often delivering applications within 24 hours of receiving requests.

“They would tell us what they needed for tomorrow, and we would work overnight to deliver it the next day,” Marchiori said. “They needed it for planning, for rescuing people, for knowing where they had to go.”

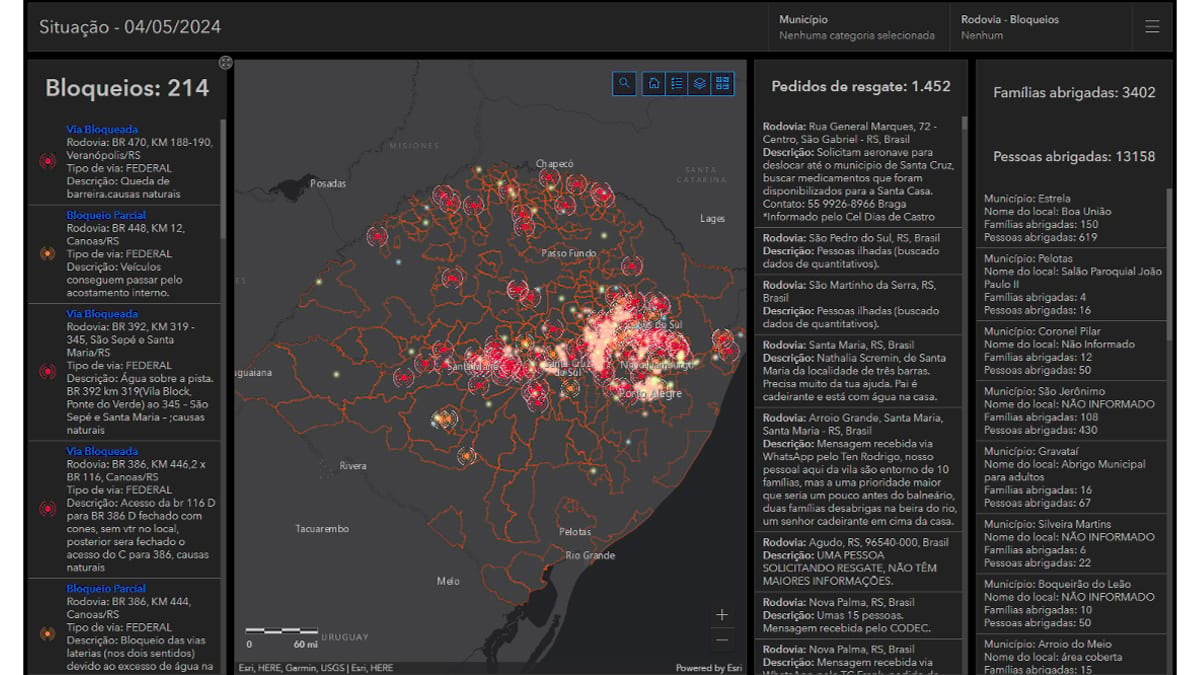

The Codex team ended up creating a suite of decision-support tools that could convey the full scope of the disaster. In 30 days, solution engineers made 17 different applications, each addressing critical needs that emergency planners in the city, the region, and in the country had never anticipated.

The first application mapped road blockages in real time. Civil defense teams in the field sent coordinates via mobile phones, and within hours, Codex updated maps showing which routes remained passable for rescue operations. Red dots scattered across digital maps became the difference between dead ends and quick routes for emergency responders.

Another application identified vulnerable populations—people with mobility impairments, including residents who are blind and elderly people who needed assistance to evacuate. “They needed to know where the people who needed help were located to get them out of their homes,” Marchiori said.

Drawing on Marchiori’s meteorological expertise, Codex developed a flood forecasting tool that showed what would happen as water levels continued to rise. The application allowed officials to model different scenarios—if water rose another half meter, which schools would be affected? Which buildings designated as shelters would be flooded?

“We could see that the water was still rising, and it was still raining in the highlands,” Marchiori said. “No one knew what the next morning would bring.”

Browsing Esri’s Disaster Response Program solutions, the Codex team adapted a flood simulation tool. Within hours, they had contacted an Esri solution engineer, obtained the code, and adapted it with local elevation data. Within two days, they had delivered a working application that could show exactly which areas would flood at different water levels.

“You can play with the water level,” Marchiori said. “If it’s going to rise another half meter the next day, you can see which areas are going to be affected. That was really helpful because it guided local authorities not to put a shelter in a place that was going to be flooded in the next two days.”

The team also created detailed 3D models of flooded areas, damage assessment dashboards, and economic impact calculators. State officials needed to quantify losses to receive federal disaster funding. The GIS applications showed how many businesses would lose 50 percent of revenue if water reached one meter or face total loss if it went higher.

Codex found another way to help beyond the frenetic building of apps. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) needed space to coordinate aid for displaced immigrants who had been living in low-lying neighborhoods. Codex offered them a room in their headquarters. The office became an impromptu humanitarian hub, with UNHCR officials working alongside GIS technicians to coordinate relief efforts.

When disaster response shifted to recovery efforts, Codex developed a platform that empowered private companies to adopt damaged infrastructure directly—schools, hospitals, parks—and offer funds and services to rebuild them.

One beverage company adopted the city’s largest damaged school, completely rebuilding it with new equipment, furniture, and technology. “Private companies managed all the spending,” Marchiori said. “It was much faster and more effective than traditional approaches.”

The platform became a model for bypassing bureaucratic delays while ensuring accountability through transparency and corporate responsibility.

Cleanup work revealed the disaster’s staggering scope. Mountains of debris—eclipsing the size of a football stadium—accumulated throughout the city. Every piece of wooden furniture touched by floodwater was ruined. The city estimated that three years would be needed to process all the debris through recycling programs.

Marchiori also hopes to clear away outdated assumptions about meteorology and disaster preparedness. “Extreme weather is accelerating,” he said. “All the studies, especially of risk areas, must be revisited and expanded.”

Now, one year after the flood, some infrastructure improvements have been made, including raising electrical panels for the pump stations. A new meteorological monitoring system is planned but is still in the bidding process. There is hope that this event will change how the country prepares for future events.

“Brazil has been a reactive country,” Marchiori said. “We only do things after the disaster strikes.”

Today, Codex continues negotiations with other Brazilian states, knowing that similar disasters are inevitable. Parts of the team’s flood response toolkit developed for the Rio Grande do Sul floods have been used in smaller emergencies, but the comprehensive system awaits the next major crisis.

“It’s probably going to happen again,” Marchiori predicts with the matter-of-fact certainty of a meteorologist. “And at that point, they’re going to call us for an emergency contract, and everything will need to be ready for the next day.”

Codex’s response to the Rio Grande do Sul floods demonstrates how much people need clarity when traditional systems fail. When infrastructure collapsed and institutions stumbled, GIS maps provided a clear vision of the crisis to guide effective response. When extraordinary events defied all planning, GIS proved its worth—not just as a technology, but as a means to empower human resilience. The small team of technologists at Codex showed how maps can become lifelines.

The Rio Grande do Sul floods of May 2024 may have been a once-in-ten-thousand-year event for Brazil, but on our changing planet, the lessons learned along with the solutions developed will likely be needed somewhere else tomorrow.

Learn more about real-time solutions to modernize emergency management operations.