July 19, 2022 | Multiple Authors |

September 5, 2023

The thought of so-called forever chemicals coursing through bodies of water or across the earth’s surface paints an ominous picture. Substantial efforts are now underway to combat per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a notoriously pervasive class of contaminants. In Wisconsin, teams are mapping the prevalence of these dangerous chemicals in drinking water supplied by two of the world’s largest lakes.

“We all have PFAS in our blood at this point,” said Melanie Johnson, director of the Office of Emerging Contaminants at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (Wisconsin DNR). “We’re all kind of dealing with it.”

Since the 1940s, toxic chemicals have been used to create a multitude of industrial and consumer products, including firefighting foam and household cleaners. PFAS have traveled through water systems, poisoning wildlife, and people. Health care professionals have tied these chemicals to liver and immune system issues in both humans and animals. Researchers continue to study the damaging effects of long-term exposure.

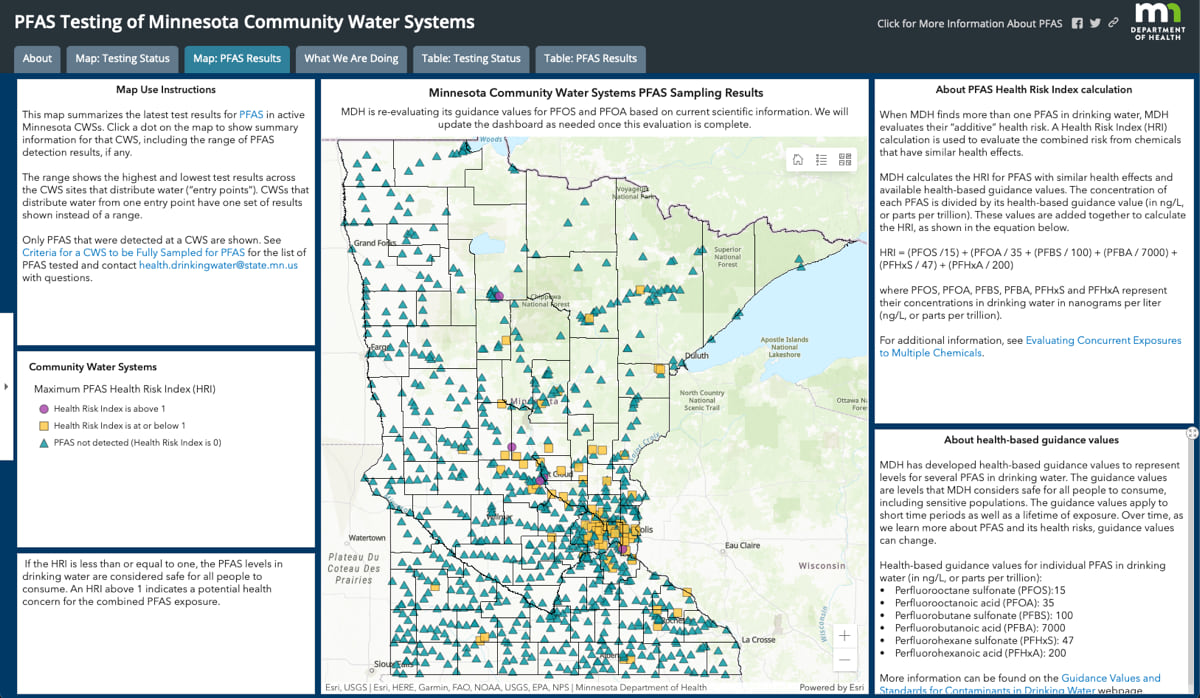

As the understanding of the risks associated with PFAS continues to grow, governments around the world are sampling water and mapping PFAS concentrations using geographic information system (GIS) technology. The maps provide target areas to address the presence of these enduring chemicals.

After Wisconsin DNR identified PFAS contamination levels that exceeded health recommendations in five communities, staff began implementing measures to address the problem.

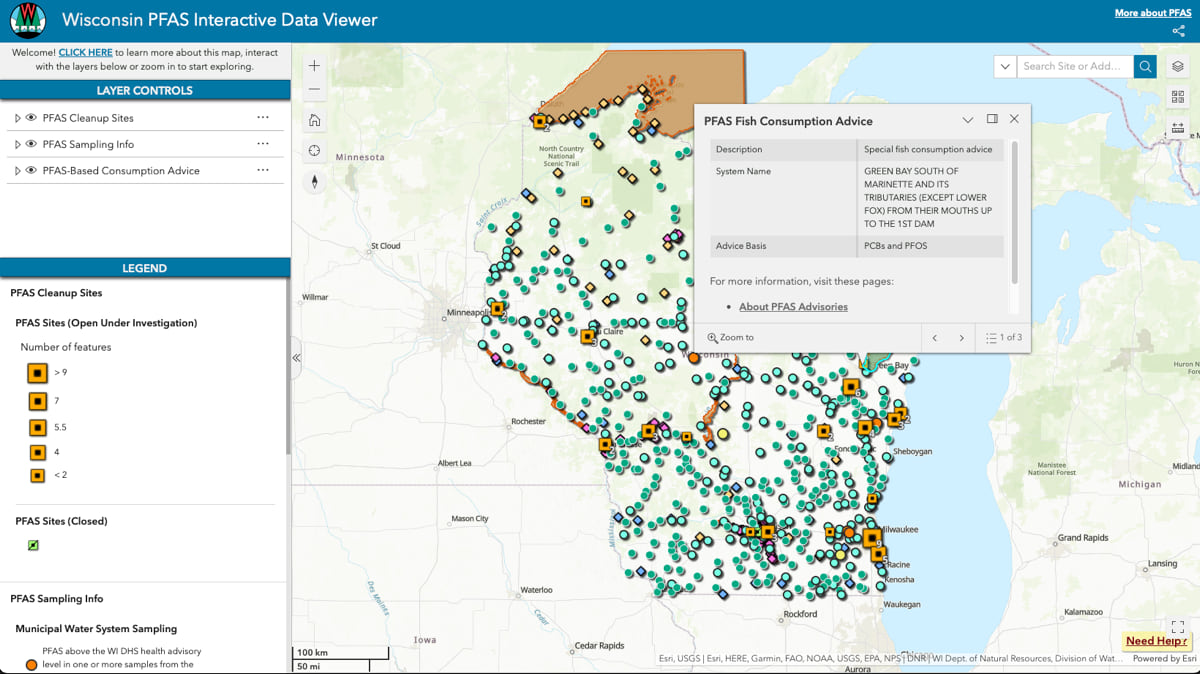

Spearheaded by Johnson and her colleague Jesse Papez, section supervisor for the GIS Data Analysis and Integration Section, Wisconsin DNR developed the Wisconsin PFAS Interactive Data Viewer to visualize the occurrence of PFAS across the state.

“PFAS have been around for almost 100 years,” Johnson said. “Two or three years ago, there were about 3,000 chemicals that we knew about, and now we’re at 10,000. We’re learning something new every day—learning how they behave in the environment, and how they impact our health. We’re starting to understand a lot more about the science behind them and what we can do to mitigate their impact.”

Companies that create and use PFAS are under intense scrutiny. They also face lawsuits for contributing to water pollution.

The European Union has proposed a ban on the production, use, and sale of about 10,000 of these substances. In Japan, the government focused on improving water quality after a group of residents in Okinawa had high levels of PFAS in their blood. Recently, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed the first-ever national drinking water standard for six PFAS. With the recent funding, the EPA plans to help communities on the front line of the fight against forever chemicals.

Wisconsin is one of several Great Lakes states that have made PFAS a priority to keep their residents and abundant water resources safe. They do this by increasing testing, setting clear standards, and openly sharing their progress.

Wisconsin is bordered by two of the world’s largest lakes, Lake Superior and Lake Michigan. With more than 1.6 million residents depending on these lakes for their drinking water, lowering PFAS levels has become a critical health priority.

For Johnson and her team, GIS provides a better view of PFAS pollution and the health of water systems that are contaminated and most in need of ongoing cleanup.

“I think there’s great value in visualizing it,” Johnson said. “One of the things we really wanted to visualize is the drinking water results.”

With the help of the PFAS data viewer, the Wisconsin DNR team can map contamination sites as well as locations where remediation efforts are underway. By visualizing and integrating this extensive location-based data, the team can effectively plan strategies, allocate resources, and share information.

Initially, Wisconsin DNR focused on remediation sites, while conducting statewide sampling of surface water and wastewater treatment plants. Staff aim to broaden their understanding of fish and wildlife contamination by sharing data and collaborating with neighboring states.

“If we’re studying a specific fish, we share that data with the other states and they share their data,” Johnson said.

Wisconsin DNR led the effort to study the smelt found in Lake Superior and issued a public advisory not to eat more than one meal of fish per month due to high levels of PFAS. That finding was confirmed by studies conducted in Michigan and Minnesota, and those states followed up with their own warnings.

One of Wisconsin DNR’s primary objectives is to ensure effective communication with the public. Through the Wisconsin PFAS Interactive Data Viewer, the team aims to provide a user-friendly interface for essential information. Anyone can navigate the PFAS data viewer to determine if there is any contamination within their area. Stakeholders, including those interested in detailed raw data or the history of a contaminated site, can delve deeper.

“We had a design goal of keeping it as intuitive as possible, yet as information rich as possible so the learning curve would be minimal,” Papez said, adding that the goal included “providing as much data as we could without it being overwhelming or requiring data science skills.”

Wisconsin DNR recently received funds from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to address emerging contaminants and ensure excellent water quality. Johnson and her team believe that tools like the Wisconsin PFAS Interactive Data Viewer will play a crucial role in gaining stakeholder support to tackle PFAS, not only at the state level but also nationally.

“This tool can be very helpful for legislators to understand if PFAS contamination has been detected in their districts and how it impacts their constituents,” Johnson said. “As more communities witness the impact of PFAS, it will become more of a unifying issue.”

Continued sampling will improve understanding the need to reduce PFAS contamination levels and break the cycle of forever contamination.

In the US, the Great Lakes states have been quick to act on PFAS, given their role as stewards of 95 percent of the fresh surface water in North America. More states are taking on this problem, starting with testing, and putting test results on a map. As PFAS contamination becomes more understood and strategies emerge, maps will be central to the worldwide cleanup effort.

Learn more about how GIS is used to monitor and manage water quality.

July 19, 2022 | Multiple Authors |

May 16, 2023 |

May 24, 2022 |