We work to figure out specific challenges that each place is experiencing, and then how we can help the government of Afghanistan meet these challenges.

April 13, 2020

A rough road has repercussions. It can cut off a village from markets, education, jobs, health care, and social networks. In Afghanistan, the World Bank administers the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund, which is investing in transportation and infrastructure improvements in support of economic well-being and mobility. But to prioritize road paving and infrastructure projects, the World Bank must gather data to map the region’s existing roads, villages, and infrastructure.

In Afghanistan, there are many barriers to traditional on-the-ground data collection. It is a rugged country with tall mountain ranges, arid deserts, and untamed rivers, and the security situation is dangerous and unpredictable.

“Afghanistan is what the World Bank calls a fragile, conflict- or violence-affected state,” said Walker Kosmidou-Bradley, a geographer in the Poverty and Equity Global Practice at World Bank. “It’s very difficult for the World Bank staff and our ministerial counterparts to move around the country and actually see the projects and get a feel for things.”

So World Bank staff and in-country volunteers took a modern approach to mapping, one that involves high-resolution satellite imagery and desktop tools to create geospatial data while working remotely. They also gathered data, such as the location of health facilities, from the country’s government agencies.

The effort to map regions and pave roads is already proving beneficial to people who live in Afghanistan.

“I used to drive on the unpaved road on my motorbike taxi truck,” said Zarkarim, a taxi driver in the Mir Bacha Kot district, as told to a World Bank videographer. “It would bounce along the road and get damaged due to the rough road conditions. Now I drive on the road happily, and I cheer all the way. I can transport goods four to five times a day; while in the past, I could make just one trip.”

The impact on Zarkarim’s village from a recent road paving project is a perfect example of the World Bank’s goal with every project. Staff work across the sectors of transportation, energy, water, agriculture, education, health, and public administration to help eliminate extreme poverty and increase shared prosperity.

To map and analyze geospatial data—which details the who and what of a country in the context of place—the World Bank relies on geographic information system (GIS) technology. GIS helps answer such questions as, Who has physical access to education? What is the carrying capacity of a region’s roads? What is the water quality and state of water/wastewater infrastructure? Who has electricity, and what is the energy capacity? What areas are at risk of disasters?

“We use a lot of geospatial data generated by various World Bank sector teams and the Afghan ministries to understand first what a country has,” said Kosmidou-Bradley. “We combine data and analyze it to get a more complete picture—to see gaps and how to fill those gaps.”

Most of the poorest people in Afghanistan live in remote, rural communities that are largely unmapped, and many of the roads have become impassable due to decades of conflict. As the World Bank expanded its operations into studying and alleviating patterns of poverty in Afghanistan, staff found they needed better data. They also needed to be able to load that data onto an accurate basemap.

“There’s a spatial context to poverty,” Kosmidou-Bradley said. “Some of the questions that we answer are not just what makes people poor but what makes people poor in different places. Sometimes there are commonalities across regions or a particular challenge to one.”

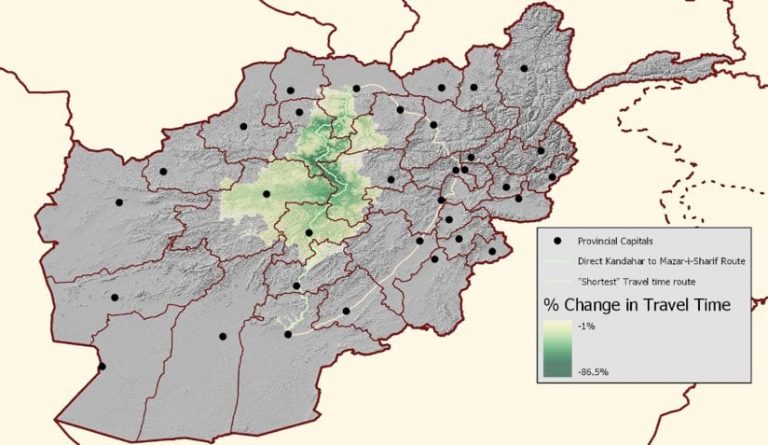

Since 2017, the World Bank and the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund have been working with Afghanistan’s Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development and the Ministry of Public Works to build more than 2,200 kilometers of new roads and upgrade and maintain more than 6,000 kilometers of existing roads. For this effort, the teams desperately needed updated road data because many of the small roads that connect each village were unmapped and unknown to those outside the local community.

To tackle this massive mapping project, Kosmidou-Bradley gathered imagery, reached out to ministries for data, and recruited a volunteer force of Afghans and interested mappers from around the world. The volunteers were trained on OpenStreetMap and were shown how to digitize features from the images, adding roads, land use (e.g., commercial, residential, agriculture, industrial), and the location of villages, mosques, schools, health clinics, and markets.

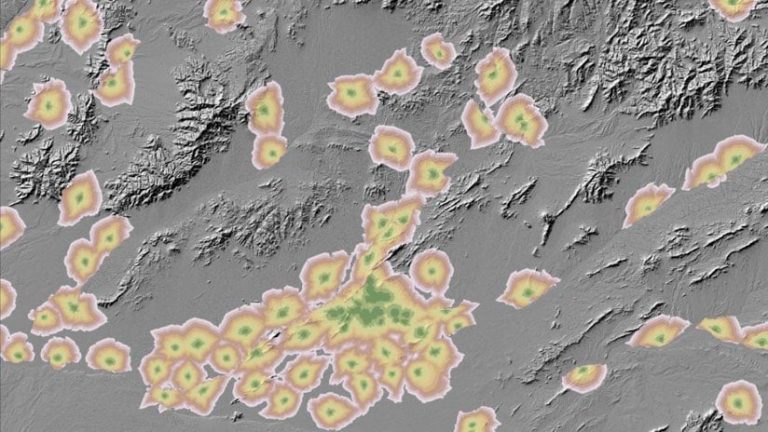

A key function of these activities was to trace roads and link them to the existing network. The volunteers also captured important details, such as whether the roads are paved, gravel, or bare earth, to help calculate transit times based on road conditions. The data-gathering effort helps prioritize maintenance and upgrade activities.

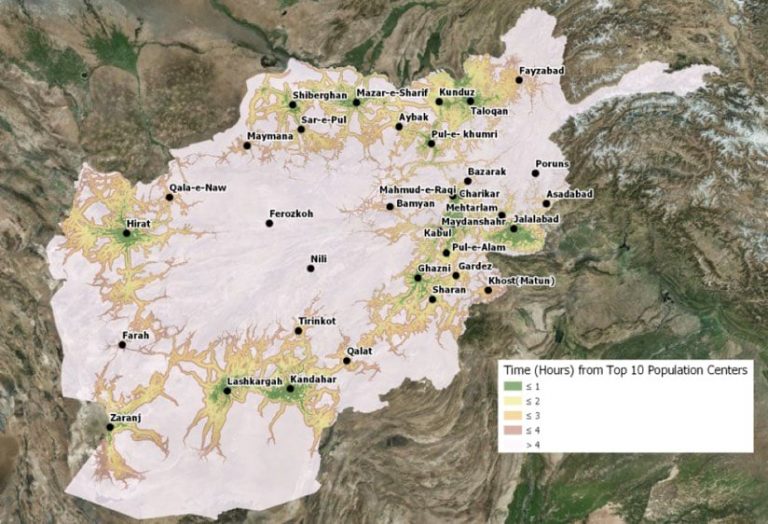

“Historically, we forecast road improvement impacts with point-to-point reduction in travel time,” Kosmidou-Bradley said. “Now, we’re looking at spillover effects such as the number of villages that have a reduced travel time to a major economic hub. Those connections have ramifications for improved returns from agriculture—turning surplus crops into money for households—and other livelihoods.”

We work to figure out specific challenges that each place is experiencing, and then how we can help the government of Afghanistan meet these challenges.

The data-driven engagement that comes from this enhanced mapping provides Afghan ministries and those within the World Bank’s sectors with the ability to conduct more in-depth analysis to structure further interventions.

The fact that this effort first centered on transportation networks speaks to the importance of roads. The World Bank team views connectivity as essential for the effective delivery of all services. To address gaps in road networks for all villages, staff knew the team needed accurate maps.

“We developed a cross-country mobility model to assess accessibility for such things as health care,” Kosmidou-Bradley said. “It can be run for people who are walking or driving, and it factors in barriers—you could be 200 meters from a health clinic, but if there’s a river between you and the clinic, you can’t get there.”

Now that World Bank staff have a more accurate road network for Afghanistan, they can run their mobility model against a large number of accessibility questions. The other side of the equation is capacity—not just how accessible a clinic or school is, for example, but how many people can be served there. This analysis helps determine whether, and where, more facilities are needed. And again, with spatial analysis, World Bank staff can help determine where best to site these new facilities.

“We work to figure out the specific challenges facing each place and then leverage different resources to help the government of Afghanistan meet those challenges,” Kosmidou-Bradley said. “Transitioning from ‘What is the data environment?’ to ‘What is the data telling us?’ speeds up the decision-making cycle and impacts action.”

Each spatial analysis effort aims to improve the impact of every project; and with each project, the war-torn country gets knitted back together.

Learn more about spatial development for Afghanistan and how GIS aids sustainable development.

September 10, 2019 |

September 24, 2019 |

September 27, 2017 |