As California’s insurance commissioner from 2011 to 2019, Dave Jones had a front-row view of the changing nature of risk. Businesses and homeowners faced more frequent and intense hazards, while residential and commercial insurance costs rose significantly.

The pressure has increased since Jones left office. CFOs have seen margins trimmed by insurance costs and disaster recovery expenses. COOs and other decision-makers are struggling to maintain business continuity as fires, floods, and storms knock operations offline.

Then as now, Jones is focused on solutions. As director of the Climate Risk Initiative at UC Berkeley School of Law, he rallies industry players around mitigation practices that bring down risks and costs on all sides.

In this conversation, Jones offers a candid view of the hazards businesses face, along with steps they can take toward using geographic awareness to lessen risk and cost. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Among today’s business leaders, what is the outlook on climate risk?

Globally and in the United States, there’s increased awareness and attention to both the physical impacts as well as the transition impacts of global temperature trends. They’re beginning to land—particularly the physical impacts. If you look at insured natural catastrophe losses globally, some portion of which is driven by business losses, last year the insured NatCat losses were about $147 billion, and that exceeds the rolling 10-year average by 20 percent.

So, the risk and size of losses continues to rise. That means that companies that are exposed to physical loss as well as those that are exposed to transition risk—which is the potential financial consequences of a transition away from certain high-emitting sectors as markets and technologies and regulations and policy make changes to try to address global temperature trends—also are increasingly paying attention to it as well.

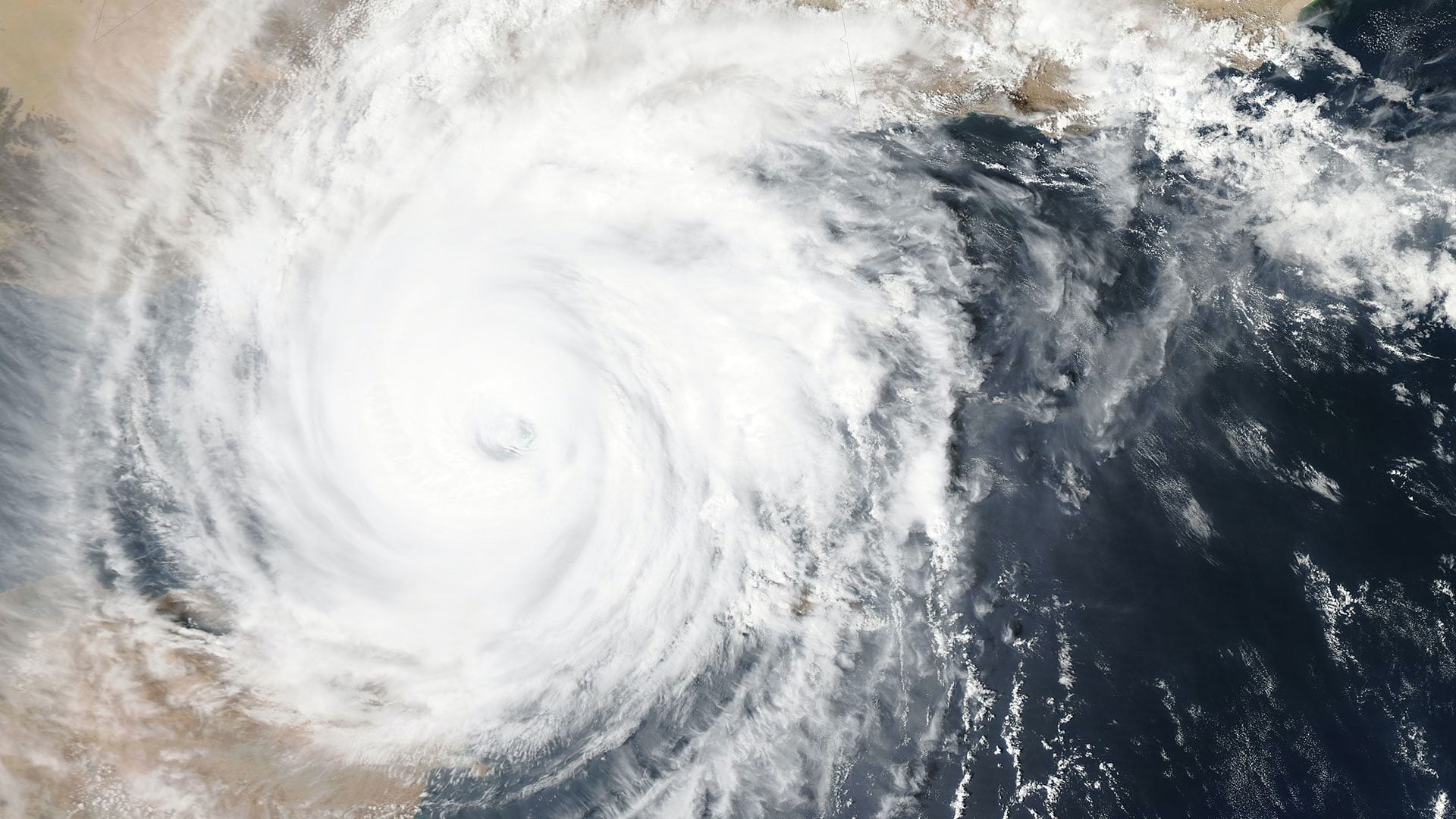

As if that were not bad enough, the climate scientists tell us that global temperature rise is projected to continue because we’re not doing enough, fast enough, to reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases. Last year we exceeded the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold above preindustrial levels. And the projections are that we’re going to hit that 2 degrees Celsius measure in short order and then go above that. That has cascading effects in terms of more severe and extreme weather-related events and more physical losses and physical damage.

How are the physical risks to a business changing?

Global temperature trends are not only making worse wildfires, hurricanes, extreme heat, drought, tornadoes, and other hazards, it is also effectively creating new hazards that cause substantial losses. If you had asked an insurance professional 20 years ago, “Are you concerned about severe convective storms?” they would have looked at you blankly. Forty percent of the insured natural catastrophe losses globally last year were from severe convective storms, and roughly the same percentage in the United States.

What are severe convective storms? Well, global temperatures are rising. The atmosphere holds more moisture in the form of water vapor. Climate patterns are changing. So, these atmospheric rivers sit on top of geographies and let down rain—heavy rain, sometimes it’s hail—but also for sustained periods of time.

That’s causing damage to business properties and homes and is increasing insurers’ losses.

Those storms are landing in the Midwest. They’re landing in the interior South. They’re landing in the West. They’re landing in New England. In 2023, four insurers actually closed shop in Iowa because of the losses they were having from severe convective storms and wind.

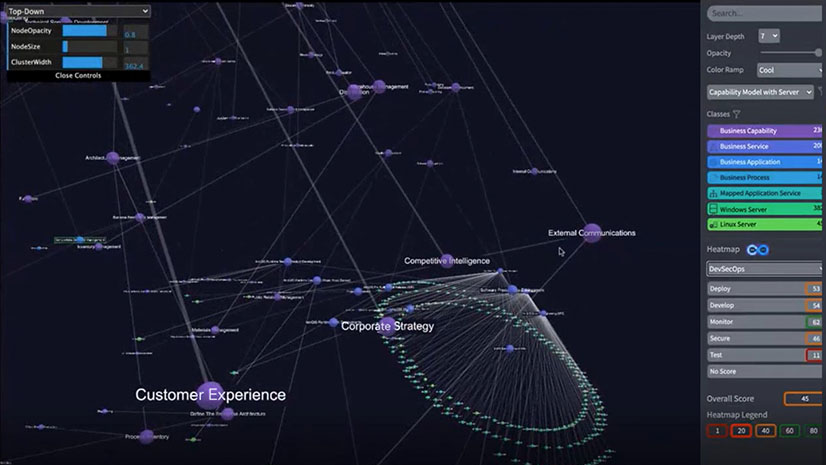

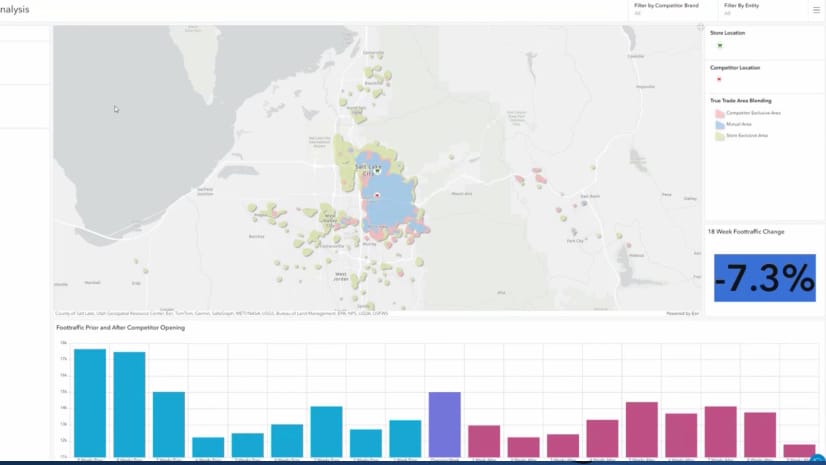

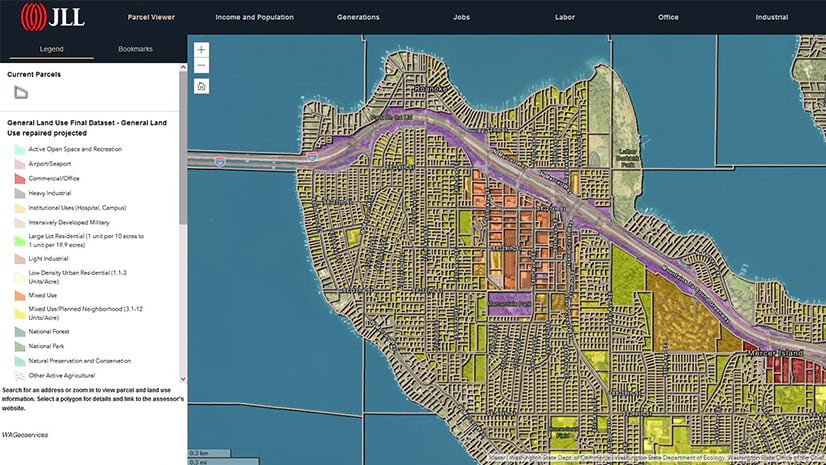

The ability to map where these perils are landing, where they are projected to land, and where nature-based solutions are being applied that demonstrably reduce risk is very useful—to policymakers, land use planners, cities, counties, states, hopefully the federal government, and the insurance industry, to name but a few. [It’s also useful] to private businesses to understand, ”Where is my business property and what is it proximate to?” and ”What are the natural catastrophe risks that my business faces in the geography where it is located?” and “What are the risks that my supply chain faces and that my distribution channel faces?”

Mapping is incredibly, incredibly important.

Enterprise Risk Management—How Companies Can Manage Threats

What steps are companies taking to mitigate exposure?

Larger commercial enterprises have enterprise risk management components that are looking at ways to try to reduce their exposure. Smaller and medium-sized businesses—they have less capacity.

But part of that, for all of them, is a dialogue with their commercial insurance company. For larger commercial firms facing hazards to property that they own in various geographies, they’re better positioned to have a conversation with their insurance company and get the insurance company to consider steps that the large commercial enterprise is taking to try to improve, adapt, or increase the resilience of its property. For medium-sized and smaller businesses, they’re trying to have those conversations, but oftentimes without as much success. [See sidebar, “Speaking with a Stronger Voice.”]

Have you seen those conversations bear fruit?

A partnership that I led through my center at Berkeley with Willis Towers Watson, which is a global insurance broker and risk advisory firm, and with The Nature Conservancy—we were able to design, structure, price, and place the first insurance policy in the United States which takes into account landscape-scale forest management. Which is an adaptation and resilience measure in western forests and in other US forests where you reduce the volume of fuel in the forest using prescribed fire and thinning, not clear-cutting. That demonstrably reduces the severity of wildfire and reduces the projected average annual losses that an insurer might face in insuring properties facing wildfire risk.

We showed insurers that forest management actually reduces risk. [The insurer] took that into account and provided for a 39 percent reduction in premium and an 84 percent reduction in deductible. And more importantly, they wrote the insurance, and they wrote it for a large homeowners’ association with 6,500 unit in the middle of the forest in northern California where other insurers are declining to write or renew insurance because they are not taking forest management into account in their underwriting and pricing models.

That’s an example that could be applied in the commercial context as well. Large commercial property owners that are in or adjacent to a forest or chaparral lands that are facing a higher risk of fire, if they’re treating those lands with thinning and prescribed fire or if they are adjacent to public-owned lands that are being treated, insurance can and should recognize the risk reduction benefit of those approaches. We’ve demonstrated it’s doable. Our hope is that other insurers will take it up.

Finding Data to Understand Risk

How does an enterprise risk management team stay informed about mitigation work that might affect them?

We’re encouraging business property owners to educate themselves about where the forest management projects are occurring, what’s the proximity to their property, and then talk to their insurance company about it.

The good news is that there’s still data available from public sources, at the state level collected and made public by state agencies. And there are private vendors collecting data as well.

For example, CAL FIRE, the California Department of Forestry and Fire [Protection], maintains an online database, which has GIS shapefiles that indicate where the forest management projects are occurring in California. [See “Resources” sidebar for details.]

Fire is front of mind for many businesses, but it’s one of many risks. Have you worked on other physical threats to businesses?

Yes, there are nature-based approaches to reducing the risk of loss from other perils which can be accounted for in insurance modeling. We looked at a nature-based solution to river flooding—in particular, a levee setback project on the Missouri River. That’s good for nature because the river can meander more—good for fish, good for plants, good for animals, good for birds. But it also reduces the risk of flooding for properties on the other side of the levee on that stretch of the Missouri, both upstream and downstream.

We took the modeling the [US Army] Corps [of Engineers] had done with regard to the flood risk reduction benefit of that nature-based levee setback project, and we demonstrated how it could be moved into insurance flood modeling and demonstrated, as we did with the wildfire approach, how this nature-based approach to river flooding reduces insured average annual losses and can be accounted for in insurance modeling.

I’m working with a team now in the Midwest to see if we can place an insurance product that is taking into account the risk reduction benefit of various nature-based approaches to flooding for tributaries of the Missouri River.

It’s important to continue to be empirical, to be science-based, to draw on the best data available, present the results, and be transparent.

The Role of Geography in Risk

Can you talk about the role of geography in a company’s physical risk?

There’s no question that the nature of climate-driven perils varies based on geography. In the Gulf and Atlantic states, the primary peril is wind. But now severe convective storms are giving wind a run for its money. In the West, it’s wildfire. In the Midwest, historically it’s been tornado, but now, increasingly, severe convective storms. And then due to temperature rise, we’re seeing an increased incidence of wildfire or severity of wildfire in places like Massachusetts or Minnesota or the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where this was never really a major issue.

So yes, geography matters. Topography and the natural environment matters. I’ll give you an example of that. After Superstorm Sandy, The Nature Conservancy and UC Santa Cruz and the US Geological Survey, USGS, did a study that looked at the losses along the Atlantic coast associated with Superstorm Sandy. And what they found was that those communities that had intact salt marshes in front of them suffered about $600 million less in economic losses than those that didn’t have intact salt marshes. The natural artifact in that geography matters, and makes a difference in terms of risk of loss.

Meeting the Moment, Making the Transition

As physical risks increase, what do you see as key elements of a transition plan for manufacturers, retailers, and other private businesses?

There are some terrific frameworks that I would direct your readers to. There’s a transition planning framework that’s been developed the Transition Plan Taskforce, now overseen by the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation. They have sector-specific transition planning frameworks and guidance that are very useful for small, medium, and large businesses—basically a checklist of things that they should be thinking about and incorporating into a transition plan.

Transition planning has two broad elements. One is understanding the risks to your enterprise and what you should be doing about those. The other is, what are you contributing in terms of increasing the risk to others and yourself? Transition plans also, importantly, are a method and a process for a business to think about the risks it faces and to think in a deliberate way: What are the steps it can take to try to reduce those risks?

They’re also an important process to think about, How is my business contributing to the underlying drivers of these climatic events? And that is looking at scope 1, scope 2, and scope 3 emissions, and what the enterprise is contributing, and what can the enterprise do to try to reduce those emissions over time as well?

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

November 18, 2025 |

July 25, 2023 |

September 23, 2025 |

January 6, 2026 |

November 24, 2025 | Multiple Authors |