Last year, Minneapolis-based Xcel Energy became the first major US utility to commit to being carbon-free by 2050. Shortly afterward, Xcel competitor Platte River Power Authority, located in Colorado, announced it would end carbon emissions by 2030. In the wake of these moves, a wave of smaller utilities followed with plans to decarbonize on even shorter timelines.

It was a sign that for many operators, clean energy is no longer just an environmental or political prerogative; the incentive to decarbonize has increasingly become an economic one. The market is reaching a tipping point where wind and sun power are becoming cheaper than fossil fuels, and decentralization, demographic changes, and digitization are accelerating the transition.

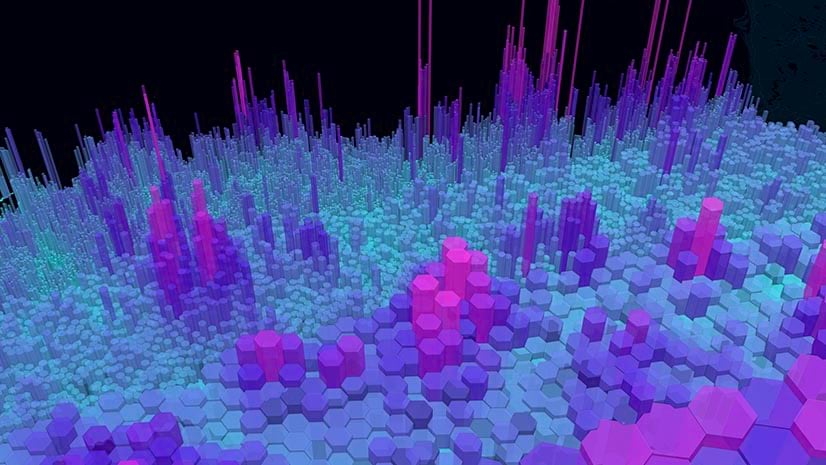

Meanwhile, utilities are in the midst of a paradigm shift toward a more customer-centric model, built on rich data about where demand is and where it will be in the future. This calls for agile technologies that can provide real-time, highly detailed consumer updates. Increasingly, utilities are turning to a GIS, or geographic information system, to guide location-based decisions about everything from managing load on the grid to siting renewable energy infrastructure such as wind turbines and solar panels.

Another relevant application of GIS has been its ability to provide deeply nuanced portraits of customers based on neighborhood, profession, age, income, and other demographic variables. It’s a perspective that recognizes the powerful new centrality of consumer choice, as well as the increasing diversity of energy consumers.

A New, Customer-Focused Model of Energy

Utilities once viewed customers as more or less anonymous ratepayers, broadly classified as residential, commercial, or industrial. Today, utility executives require a far sharper understanding of consumers, addressing questions about who is most likely to buy an electric vehicle (EV) or install solar panels, what neighborhoods will need charging stations, and where to offer incentive programs to manage load.

GIS-powered mapping applications can model customers and their usage habits with geographic accuracy to help answer these questions. Fast-growing groups like environmentally concerned Millennials and “prosumers” (adapters of green energy who themselves supply power), as well as other demographic trends, make incorporating GIS-based location intelligence into a business strategy even more advantageous.

With growing demand from the public for access to clean energy, as well as studies that project long-term savings from sun and wind power, many utilities have moved beyond deciding whether or not to prioritize a switch to clean energy. They are now gauging how quickly and smartly the transition can be made.

Clean Energy’s Economic Tipping Point

As the costs of green energy drop while its effectiveness increases, the economic argument for decarbonization has become difficult to ignore. According to one estimate, the total capacity of solar and wind generation in the US grew from 9.5 gigawatts in 2005 to 113 in 2017.

A study by renewables analysis firm Energy Innovation found that around three-quarters of US coal production is costlier than wind and solar energy in supplying households with electricity. When you account for subsidies, the megawatt-hour cost of electricity from wind power can fall as low as $14, according to investment firm Lazard’s analysis. By comparison, running existing coal plants costs an average of $36 per megawatt-hour, while the cost of creating and operating new coal plants can be as high as $143.

Consumer choices reflect the new reality of green energy. In 2017, 3.1 million electric vehicles were in use worldwide—a 54 percent jump from the year before—according to the International Energy Agency’s Global Electric Vehicle Outlook 2018.

Utilities’ Road Map to Innovation

In the midst of these changes, utilities occupy a paradoxical position. As highly regulated, vertically integrated monopolies, they tend to be risk-averse and slow-moving. At the same time, they are extremely attuned to future trends.

“Most people think utilities aren’t very forward thinking,” said Kevin Prouty, group VP of energy and manufacturing insights at IDC, in a recent podcast interview. In fact, Prouty says, “they are probably the most forward-thinking industry in the world. They’re looking 20, 30 years out.” They can see the changes to the industry coming, even if they can’t react as fast as private companies might.

Another factor that gives utilities an edge is that they are magnets for data, hoovering it up often faster than they can process or analyze it. Imagine a typical large utility with 2 million meters, Prouty suggests. If they’re collecting data every 15 minutes, that’s 8 million data points every hour for 24 hours a day.

Utilities need to make sense of all this data in a way that yields insight, ideas for best practices, and forecasts that align with long-term strategy. That’s where GIS comes into play.

“I think everything a utility does is around location,” Prouty says. “That’s why, if you look at the utility space, every utility has some form of a geospatial system. They have to.”

Austin Energy Drives EV Revolution

Lindsey McDougall, an electric vehicle program manager at Austin Energy in Austin, Texas, can remember a time when she had visited every single EV charging station in the city. “I can’t do that anymore,” she says. “There’s just too many.”

Since 2013, McDougall has overseen operations for electric vehicle adoption, with a focus on incentive programs that offer rebates to EV drivers as they use charging stations around town. Six years after these programs were put into place, Austin Energy is experiencing growing pains as adoption levels for electric vehicles multiply. “They’re coming on our network so fast,” she says.

To help deal with the tide of customers and prepare for a future focused less on incentives and more on demand response, McDougall relies on GIS and the location intelligence it supplies about customers and their habits. “GIS really provides that knowledge for me to understand what’s going on with our customers and prepare for the future.”

In particular, McDougall uses GIS-driven demographic analysis to drill down into the specifics of where demand is coming from and where it might increase in the future. By classifying neighborhoods into dozens of consumer segments organized by ZIP code and socioeconomic data, GIS can provide utilities with insight into residents’ lifestyle choices that relate to EVs as well as other forms of green energy.

By comparing the profiles of existing EV drivers to the entire customer base, Austin Energy can use targeted marketing to reach out to prospective customers about the electric vehicle programs in ways that will be most enticing.

“We can really classify them by address,” McDougall says. “Through the [demographic] data, we see how they prefer to be reached out to, via mail or email or phone.”

GIS has also had broader applications for Austin Energy in how it cooperates with the city’s political leaders to meet transportation and sustainability goals. When the Austin City Council recently revisited its Imagine Austin road map for sustainability, McDougall used smart maps to explore ways to incentivize deployment of charging station infrastructure that will create a more connected city.

When Austin Energy’s project leader presented to company executives on the deployment of DC charging stations, they did so with one of McDougall’s maps in hand. That map emphasized the wide geographic distribution of the DC stations—an important feature in Austin where council members want to ensure that all communities, especially underserved ones, are being addressed.

“GIS is used for a lot of visualizations to help us really understand what’s going on,” McDougall says. “We have to see it visualized.”

Green Energy Changes in Denmark

The shift toward renewable energy sources, and the need for agile map-based technology to help utilities accommodate it, is playing out at an accelerated rate across the Atlantic. Ørsted, based in Denmark, has become one of the world’s largest offshore wind energy developers—a remarkable turnaround for what was just years ago a foundering energy company focused on coal-based power plants and petroleum.

Under chief executive Henrik Poulson, who came on in 2012, Ørsted sold off its oil and gas holdings and put its chips in offshore wind, an aggressive bid that has rocketed the organization to the global forefront of green energy. Today the Denmark company finds itself competing with prominent multinational companies for huge international markets, with its wind farms already established throughout northern Europe. In June, Ørsted announced an offshore wind energy project in New Jersey that will power half a million homes.

Making this shift has put Ørsted in the position of managing a broad base of customers and facilities. Jakob Mortensen, head of energy analytics and geo services at Ørsted, has been at the center of some of these changes. While Ørsted was an early adopter of GIS, employing the technology as far back as two decades ago, Mortensen says the demand for location intelligence has only grown, leading the company to require newer, richer, more detailed levels of data.

“We have to look at our customers in a completely new way compared to only a few years ago,” Mortensen says. “Usually people had to buy all their electricity from one company, but now they have an option to choose their own vendor. At the same time, we also see a huge increase in the amount of solar panels on private households. We expect to see a huge increase in privately owned and company-owned batteries.”

Mortensen relies on GIS as a tool to illuminate demographic change, to predict where solar panels will become more popular, and to determine how to apply the current potential of grid capacity.

In Denmark, there are limits on the level of detail utilities can acquire about individual consumers. But even by paying attention to location intelligence on a regional level, they can identify and forecast trends. Areas with dense concentrations of academics with high incomes, for example, signal a demographic that is more likely to purchase electric vehicles.

The other major area where GIS has proven essential for Ørsted is in guiding the placement of wind farm turbines—what is now “by far the largest business area in Ørsted,” Mortensen says. Sister industries like Internet service providers are similarly relying on GIS to branch out into new regions. As Ørsted seeks to find good locations for offshore wind farms and where to lay down cables, location intelligence can also collate data relating to bird flight migration patterns, shipping lanes, and even unexploded bombs from World War II to aid placement. As Ørsted’s presence expands internationally, reliance on GIS will likely come into even greater play.

For Mortensen, the central argument for using GIS comes down to a financial one. He recalls a quote that came up at an industry conference a few years back: “Why spend billions in copper when you can use millions in software?”

Having data with a geographic awareness at your fingertips means greater efficiency, less waste, and a more confident path into the future. “We can save a lot of money by knowing more about how our grid is configured and how it’s loaded,” Mortensen says. “It’s all about knowing how to utilize your grid more efficiently.”

Putting Consumer Choice First

Utilities may be relatively slow-moving, but they can be agents of innovation. As some of the most consequential players in the shift to clean energy, they are poised like few others to employ location intelligence to prepare the grid for the future.

The relevance of GIS to new infrastructure is clear, but how GIS can connect utilities to customers may prove even more essential in the long run. In a world where consumers have more choices in their energy sources, a deeper understanding of who the customer is and what they want will be a utility’s defining competitive edge.