I view geodesign as encompassing everything on, below, and above the surface of the Earth that supports life. The planet’s geo-scape.

September 8, 2017

When Bill Miller, one of the early advocates of geodesign, wanted to get his students attention, he would say, “Let’s talk about making love.”

He wasn’t referring to romantic love of course (leaving some of his students a bit disappointed) but to that nitty-gritty kind of love that makes a difference in people’s lives… the kind of love that facilitates life. It’s an attitude of wanting to work hard on something. You infuse something with skill and passion, and see it as a gift.

Making this kind of nitty-gritty love is the passion point in Miller’s philosophy of design.

Miller defines design as the “thought process comprising the creation of an entity.” He goes on to clarify that an entity can be anything: an object, an event, a concept or even a relationship. After discussing this with his students he asks the questions: “What’s missing?” and “How do we know if a design is good or bad?”

For Miller, the design ethic (how we know if a design is good or bad) comes not from the definition of design but rather from the purpose of design. In Miller’s mind, the purpose of design is always the same: “The purpose of design is to facilitate life.” This yields a simple ethos: If a design facilitates life it’s good. If it inhibits life it’s bad. If it does neither it’s neutral.

This simplicity, however, can be misleading as one considers such things as who’s life, what aspects of life, which species, over what time span, and so forth. Exploring the depth and breadth of these considerations can serve to morph the simplicity of this ethos into a complex array of values, leading Miller and his students into a lengthy discussion.

At the conclusion of this discussion, he presents his students with the questions, “Isn’t this purpose of design ‘to facilitate life’ also a good operational definition of love?” and “When you love someone, don’t you have a desire to facilitate their life?”

Therefore, if the purpose of design is to facilitate life, which is also a good operational definition of love, the designer is a love maker, and the love the designer makes is embodied in the entities they design.

Miller relates an incident when a large rock hit the windshield of his truck as he was speeding down a country road. Fortunately, the safety feature of his windshield contained the glass fragments and he was unharmed. After he caught his breath, he realized he had a lot of designers to thank. Thanks went to those who conceived of safety glass, those who researched and validated the idea, those who engineered and manufactured it, those who lobbied Congress, and those who made it law and mandated that it be placed in every vehicle in America. They had collectively saved his life. In other words, the nitty-gritty love they created got instantiated in the windshield of this truck and he quite literally experienced that love when the rock struck his windshield.

Miller goes on to say, that when a design is perfect the physical form of that design disappears and what the user gets is total facilitation.

“Facilitation occurs when the entity is designed to give attention to what the user wishes to accomplish,” says Miller. “As opposed to get attention and distract the user from what they wish to accomplish, which is often the case.”

Miller’s ideas about design do not come from scholarly research or even from the ideas of others but rather from his own experience as a designer. Miller has worked in many fields, including architecture, structural engineering, industrial design, environmental planning, geographic information systems, systems engineering, computer programming, research, and education.

The underlying thread connecting his experiences in each of these fields has been the realization that “design” is not a profession but rather a concept that underlies all aspects of life. It represents a way of thinking coupled with an understanding that, in some ways, we are all designers responsible for influencing the projects and people that move in and out of our lives.

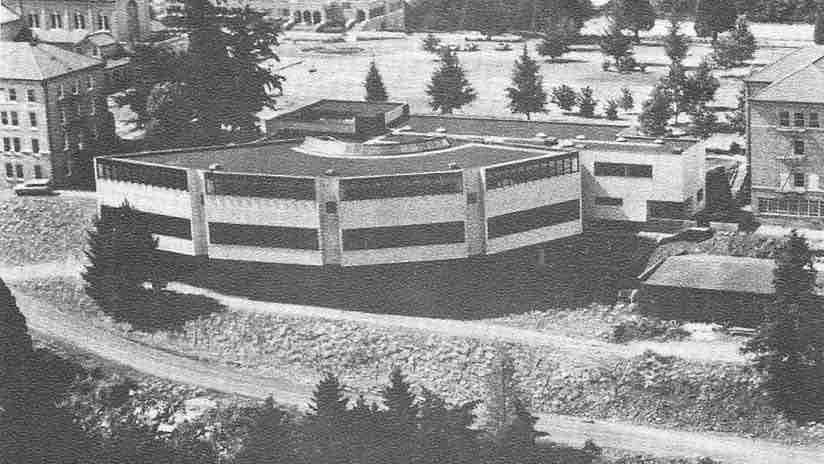

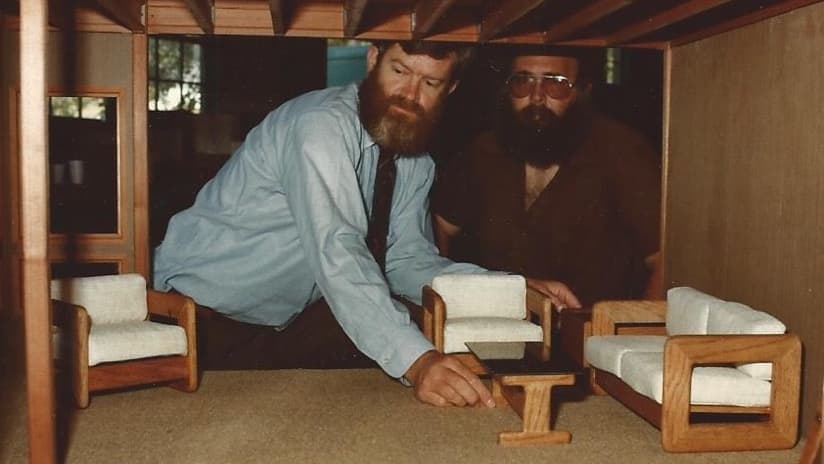

While working in London, Miller received a call from Jack Dangermond asking if he would be willing to take on the design of a housing system for Matsushita Industries in Japan. Dangermond had been working on planning projects for Matsushita and was asked if he could design a factory-built house for them. Dangermond accepted the offer and turned to Miller to lead the project.

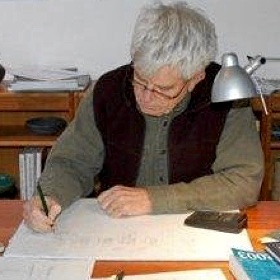

Miller took it on and ended up designing the first factory-built 2×4 house in Japan. The house was assembled on site in 7½ hours. He went on to found Shelter Research Institute (1979 to 1989) where he continued to work with Dangermond on a variety of projects, including the development of the first energy-producing house in Japan (1978), the Pana-wood housing system, and numerous technology assessment studies, including studies related to the development of electric cars and electronic work surfaces.

While leading Shelter Research, he designed housing systems for many clients. Homes designed for the Robert L. Propst Foundation used movable partitions for interior and exterior walls. Homes designed for General Electric – Plastics featured industrial-grade plastics. He also served as a design consultant to the Weyerhaeuser Corporation.

I view geodesign as encompassing everything on, below, and above the surface of the Earth that supports life. The planet’s geo-scape.

Dangermond asked Miller to join Esri in 1989. He served officially as the Director of Educational services for 15 years—re-engineering Esri’s training program, initiating Esri Press, and developing Esri’s virtual campus—while also leading several product development efforts.

Miller led development of ModelBuilder, a visual programming language for building geoprocessing models to automate and document spatial analysis and data management processes. He led the development of ArcSketch, and the subsequent formation of Esri’s geodesign agenda. As director of Esri’s Geodesign Group (2004 to 2015) he led the development of GeoPlanner, Esri’s web-based tool for doing collaborative geodesign. He was also instrumental in initiating the Geodesign Summit, Esri’s vehicle for spreading the word and ideas to the world.

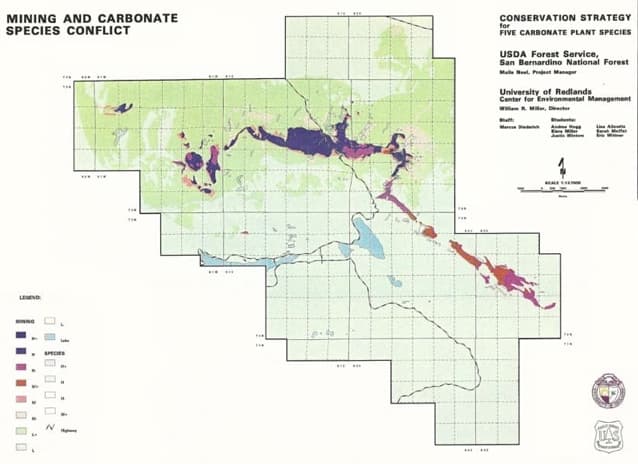

During this time, he also taught environmental planning at the University of Redlands and established the Center for Environmental Management, which became the Redlands Institute.

Miller, now retired (sort of), continues to push geodesign with the goal of increasing our understanding regarding the full potential of geodesign. He’s a strong believer in the holistic nature of geodesign and laments the fact that much of the geodesign agenda has been hijacked by regional planners.

“I’m not against the use of geodesign by regional planners but they do most of their work in two-dimensional space,” says Miller. “I view geodesign as encompassing everything on, below, and above the surface of the Earth that supports life. The planet’s geo-scape.”

The idea of geodesign applied within this broader context yields a much larger application domain, including the potential resolution of global problems, such as global warming, or even the resolution of geo-political conflict. It starts with a question about what the design hopes to improve. Next comes compiling geographic knowledge about a place down to the functions of the natural systems and the patterns of human interaction. Then a careful analysis of what might be altered and what difference the changes cause. Finally, it’s a close study of what should be changed, with careful planning of both how and when.

Miller challenges us to embrace this larger view of geodesign and encourages educators to go beyond the two-dimensional domain of regional planning. The broader application potential of geodesign exceeds the traditional boundaries of urban and regional planning.

“I always go back to Buckminster Fuller when I think of the role and responsibility of the geodesigner,” says Miller. “Fuller said, ‘we have but one spaceship-earth, we need to take care of it.’”

Keeping this view in mind is important for the geodesigner who must invent objects, events, concepts and relationships that facilitate life at all scales. This encompasses the life of individuals and communities, those residing beyond our borders, those belonging to future generations, as well as the very life of the planet.

During Miller’s last conversation with his father, just days before he died, he asked him if they should design and build a few more buildings. This was a somewhat playful question given that Miller is an architect and his father was a carpenter. His father, who could barely speak, replied, “No, we have enough buildings. What we need is more love.”

Read more about Bill Miller’s thoughts on Geodesign in, “Introducing Geodesign: The Concept.”

A gallery of Bill Miller’s designs

August 16, 2017 |

August 30, 2017 |

August 28, 2017 |