June 9, 2020 |

October 12, 2021

Jean Yang, a senior associate at the Los Angeles design firm Studio-MLA, is a self-described recovering “metrics-aholic.” Educated in economics, Yang learned to trust hard numbers, but through experience working with communities, she realized that we need to look beyond quantitative metrics to understand how to reflect community input into public space design. As Studio-MLA’s project manager for the Upper Los Angeles River and Tributaries plan, Yang is helping apply both qualitative and quantitative insights to ensure infrastructure equity in a massive revitalization plan.

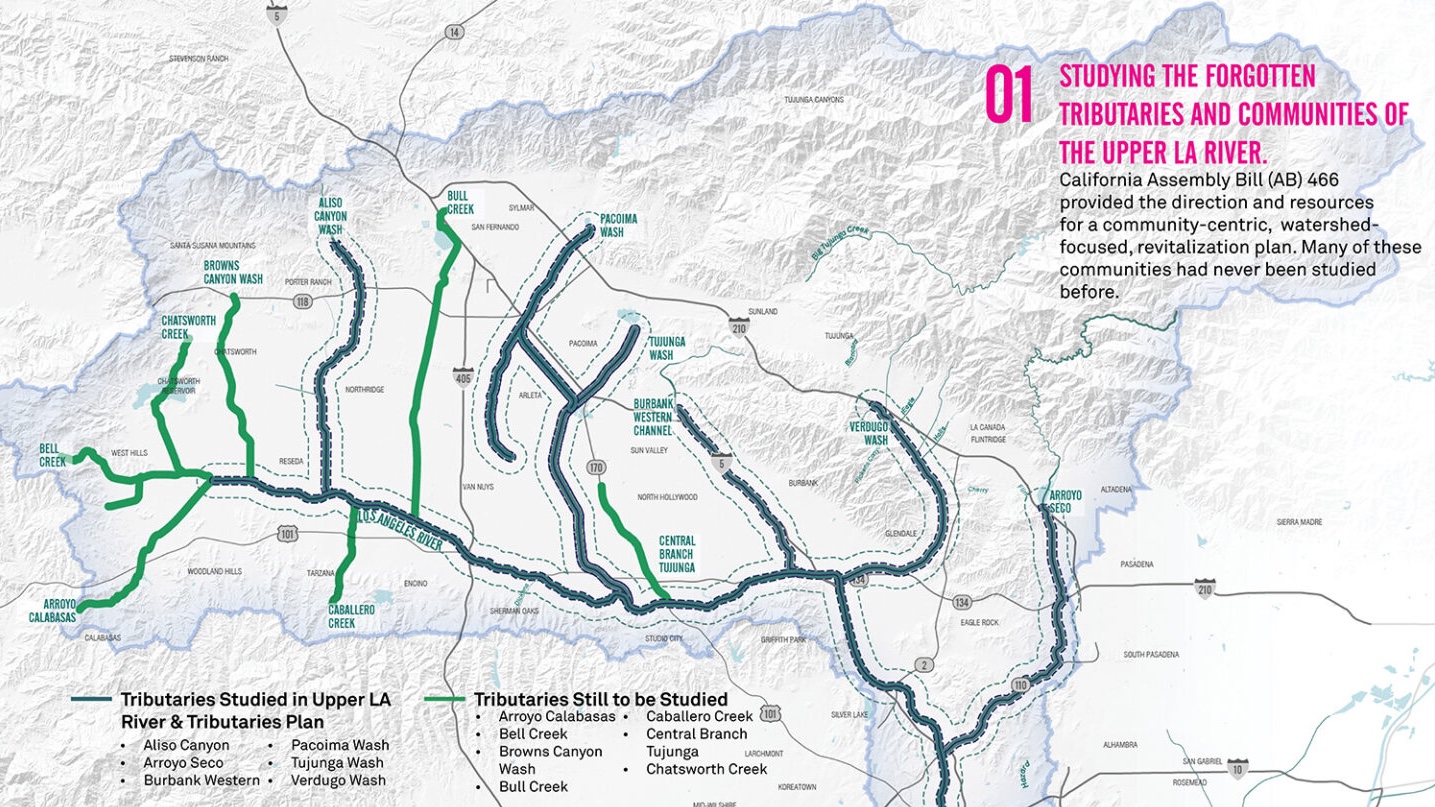

“The LA River is 52 miles long and links a variety of communities, income levels, and histories,” Yang said. “We need to understand it as a connective tissue that not only links us, but also highlights what’s special and unique about each place.”

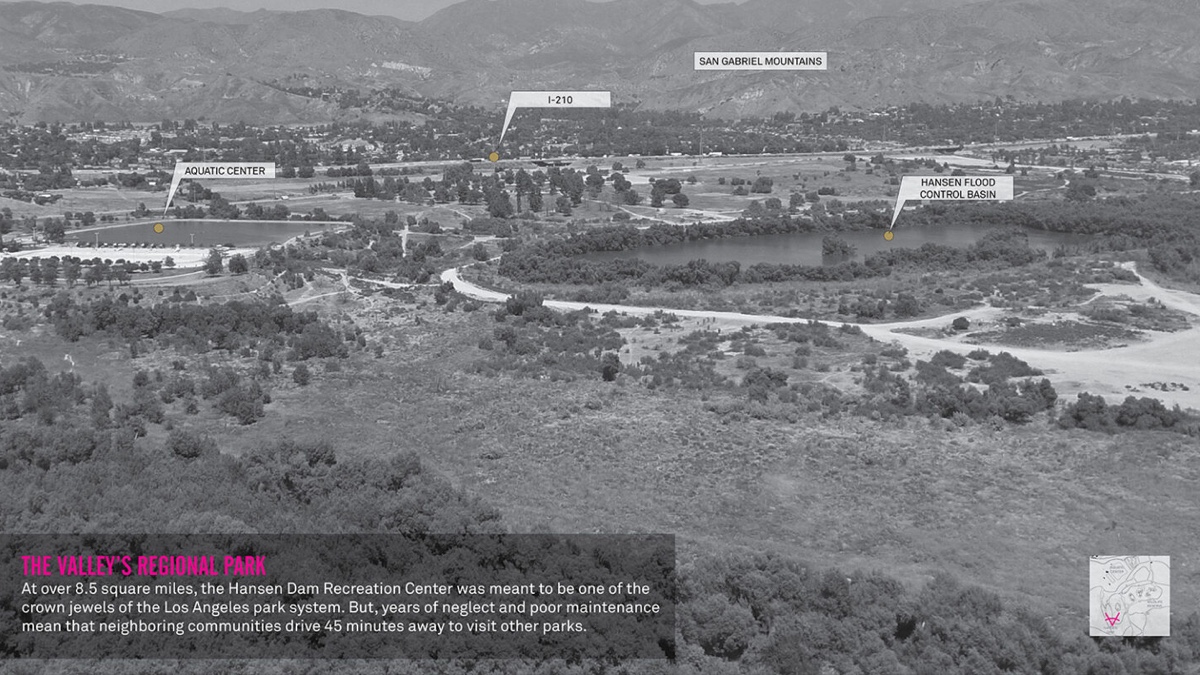

The Upper Los Angeles River and Tributaries revitalization plan identifies more than 300 recreation and conservation projects and could bring open-space amenities to more than 625,000 residents. To achieve amenities for everyone, she uses a geodesign framework supported by geographic information system (GIS) technology.

Yang’s parents immigrated to the US from China and raised her with great respect for careers in math and sciences. Though her father wanted to be a writer, he became a doctor instead, believing the medical field to be more reliable. Following her father’s advice, and having watched her family struggle with finances, Yang decided to pursue a bachelor’s degree in economics and government at Cornell University.

But another experience was influencing Yang’s career path. She recalled visiting malls in Hong Kong, which served as community gathering places with office spaces and high-end retail stores. At the time, Yang noticed how these spaces were reserved for a select portion of the population. Inspired by the idea of equitable public spaces, she went on to earn a master’s degree in urban planning from the University of California, Los Angeles, and a second master’s degree in landscape architecture from the University of Southern California.

After graduation, an internship with Kounkuey Design Initiative (KDI) took Yang to Kibera, Kenya. “Nobody actually owned [the land],” she said. Her work involved KDI’s first public space project, which cleaned up a vacant plot of land and built a playground, community space, and community office. “An open space in a private development is not going to be as equitable and accessible to multiple people as one that is freely accessible and has a playground and places where kids can be kids.”

Building on her education and experiences, Yang developed a deep understanding of how land use affects a community. From her training in economics and her skill in decoding metrics, she knew that numbers were difficult to argue against. She saw how quantitative data is used in decision-making for public spaces. But through her internship in Kenya, Yang learned that qualitative data was also, if not equally, important.

Years later, working on the LA River revitalization plan, Yang applies that sensibility and the GIS technology that supports it. She practices geodesign using GIS to capture proposals, including those from the community. Plans are displayed on smart maps so all stakeholders can view them in the context of their geographic location, give feedback, then make iterations and decisions.

Yang considers mapping visualizations to be “human-centric and understandable,” which is especially important for community engagement. “With mapping, I feel like once community members understand it . . . this new layer of interest automatically comes up because it is based on things that they’re inherently interested in, which is their community,” she said.

Members of the Upper Los Angeles River and Tributaries Working Group recognize the value of waterways and the importance of protecting the river’s watershed resources while prioritizing the needs of disadvantaged communities. Yang is using this opportunity to design spaces focused on the needs of the surrounding community, relying on qualitative and quantitative information.

To help determine which areas are good candidates for accessible and equitable recreation spaces, the work group uses the LA County Parks and Recreation equity index. “We’re layering all of this qualitative data on top of the quantitative park needs assessment, household income, what the schools are like, and what the crime rates are like to get a more well-rounded picture of where parks should be going in these areas,” Yang said.

Though Yang still admits she’s never met a metric she didn’t like, she realizes that numbers alone are not enough. To build equitable neighborhoods and create accessible public spaces, designers and planners need to understand the people in their communities. She’s seeing the impact of this approach in the LA River revitalization effort. “In a less-metric way, they are seeing themselves as community—gathering in places where you get to know each other and create this community network.”

Learn more about how geodesign helps create built places that more closely integrate with natural places. Every year, geodesign practitioners gather for the Esri Geodesign Summit to share and discover best practices, learn new tools, and see how peers are confronting design challenges head on. We invite you to join this exciting group of experts and apply geodesign your own community.

June 9, 2020 |

August 31, 2021 |

July 2, 2020 |