September 19, 2023 |

November 1, 2023

The garden-inspired settings of many US burial grounds are marked by unique architecture, sculptures, landscaping, and parting sentiments inscribed on tombstones. Few Black cemeteries have received similar adornment. From the start of slavery in 1619 until just after emancipation in 1863, plantation owners typically set aside marginal plots for burial sites of enslaved people. Black families also faced restrictions on burial locations for roughly a century after the Civil War because local laws supported racial segregation.

Now, communities across the US are rediscovering forgotten and lost Black cemeteries and documenting their history, using technology to map above and below ground. In late 2022, Congress passed the African American Burial Grounds Preservation Act, that will provide resources to locate, document, and preserve these often unmarked or abandoned sites through 2027.

Remote sensing and geographic information system (GIS) technology are aiding efforts to document remnants of burial sites after decades of neglect and often misuse. Drone imagery helps researchers see patterns from above, and ground-penetrating radar detects the location of what is beneath the soil. The data produced by these technologies is layered on GIS maps to show clear evidence of hallowed grounds even when the land is overgrown.

The national pattern of disregard for Black burial grounds left most uncounted, unprotected, and rarely documented on maps. As land ownership changed over the centuries, many Black burial sites were lost to development or neglect. Illegal dumping worsened conditions at many sites. Today, flooding and high winds that are intensifying because of climate change further threaten these fragile sites.

Families and preservation groups have more hope for rediscovering and protecting lost gravesites with the passage of the African American Burial Grounds Preservation Act. The work will give tens of thousands of families a tangible connection to their ancestors, many of whom made contributions that shaped their community’s history and culture.

“Graveyards, burial grounds, and cemeteries not only honor our ancestors; they’re also an important resource for historians and genealogists who want to tell our history,” said US Representative Alma Adams from North Carolina, an advocate for the preservation of Black cemeteries, in a press release.

The application of advanced technologies means burial sites will remain undisturbed as research teams more sharply define their features. GIS maps provide accurate positioning and documentation, enriched by layers of data from current research and historical records. In this way, the map becomes a collaboration tool for teams restoring neglected sites.

GIS maps are also being used as resources for visitors. At Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, visitors can use the Flora Mount Auburn app to take themed tours of the 175-acre grounds. African American heritage is one of the tour themes. The maps and app help visitors find their way around the property and learn about its horticulture and history, which dates back to 1831.

At C. Leon King High School in Tampa, Florida, officials announced in 2019 that a search using radar had located 145 coffins in an unmarked gravesite on campus. The tally suggested that even more remains were yet to be found in an area once known as Ridgewood Cemetery.

The New York Times reported that Ridgewood was the burial place for as many as 250 Black residents in the 1940s and 1950s. Investigators tracked land sales to determine how local agencies acquired the cemetery before building the school.

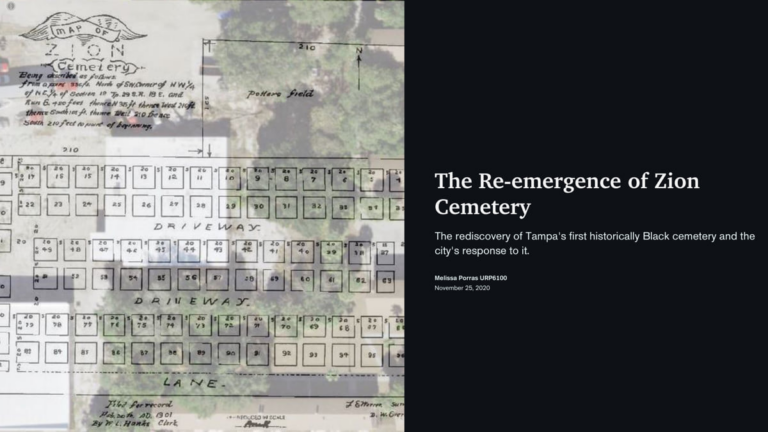

A few months earlier, radar also helped investigators in Tampa locate Zion Cemetery and hundreds more unmarked graves. Zion was the city’s first Black cemetery, and nearly 800 Black residents were buried there during segregation, according to a report by the Tampa Bay Times.

Although construction workers dug up three caskets on the site as development of the Robles Park public housing complex began in 1951, the project continued. More recently, researchers overlayed images of the burial plots onto a map of the Robles Park property. This showed that graves were still in place a few steps outside doorways and underneath lawns of housing units. A local restaurant’s warehouse operated on another section of the cemetery.

As investigations continued in Tampa, researchers located eight other Black cemeteries. Similar work began to examine suspected burial sites at Tampa’s MacDill Air Force Base and other sites across the state and the nation.

In Tulsa, Oklahoma, an invoice paid by the city confirmed that at least 18 unnamed victims of the city’s 1921 race massacre were buried at Oaklawn Cemetery, the mayor announced in April 2023. Radar and digital maps helped investigators locate the unmarked graves.

Efforts continue to find the remains of other victims of a mob’s two-day attack in the city’s segregated but prosperous Greenwood neighborhood. An estimated 300 Black people died there. News accounts suggest that some victims may have been buried in mass graves at several locations, including along the railroad tracks and in the Arkansas River.

While the state of Virginia paid for the care of Confederate cemeteries, it withheld the same benefits for burial sites of the formerly enslaved until 2017, according to an article published in the International Journal of Historical Archaeology. Access to family genealogy and local Black history was more limited there as a result.

One of the largest preservation efforts for Black burial sites focuses on two cemeteries in and adjoining the city of Richmond. Tens of thousands of now mostly unmarked graves are scattered across more than 76 acres at East End and Evergreen Cemeteries.

Two neighboring Black burial places that also suffered from neglect—the 30-acre Oakwood Cemetery (1917) and the four-acre Colored Paupers Cemetery (1896)—added to the urgency of preservation work.

A research team used GIS technology with drones to find burial sites at the 16-acre East End Cemetery and the Colored Paupers Cemetery. East End Cemetery is considered one of the area’s most significant memorial gardens because its opening in 1897 gave Black mourners a dignified place to grieve and remember those who died. Among those interred were doctors, ministers, and bankers. Many were born enslaved.

When researchers processed the drone-captured images of East End Cemetery using GIS technology, they detected oblong depressions in the soil. With this analysis, they were able to document and map 8,000 graves. Volunteers separately located 3,300 marked graves. A map now identifies the location of each.

By recording the dates on grave markers, researchers offered evidence of the chronological development of East End Cemetery section by section. The team followed the same processes to confirm gravesites in the Colored Paupers Cemetery.

As the preservation of Black burial grounds progresses across the US, crucial pieces of the puzzle are emerging to further our understanding of the nation’s history. Advances in technology are making the work more successful and efficient.

Learn more about how GIS is used for cemetery management and record keeping.

September 19, 2023 |

October 3, 2023 |

April 27, 2023 |