Nearly a decade after the global financial crisis, as banks continue to adjust to a raft of new regulations, some are prioritizing going above and beyond the call for compliance and focusing on a new bottom line that incorporates doing well by doing good.

One of these is Regions Bank, a Fortune 500 company with 1,527 banking offices in 15 states, total assets of $126 billion (2016), and more than 22,000 employees. “Shared value”—doing business in a way that benefits the customer, the company, and the community—represents a core tenet of the bank’s mission and its business strategy and is viewed as the best path to a sustainable business model. After all, as the bank notes in a statement about its culture, “The company will only be as strong as the communities we serve.”

But stating that “Regions makes life better” and putting that slogan into action are two different things. For Regions—as for a growing number of banks and businesses—the finely tuned geographic and demographic information that can be accessed through location analytics technology has become a key tool for making sure the actions match the mission.

The Speed of Digital Transformation

Regions’ growing reliance on location analytics began five years ago as the banking sector was emerging from the 2008 crash. The bank beefed up its risk management department by creating its first Spatial Intelligence and Location Analytics group—a unit that used geographic information system (GIS) technology to help track branch locations.

At the time, most banks were stapling paper maps to a wall and marking them up with Sharpie pens to make sure that prospective branch locations met federal requirements to serve low-income communities, while also weighing the other factors that drive location decisions (land price, neighborhood demographics, available talent pool, competition, etc.).

Without the technology and without the science to back things up, you become dependent on essentially gut feelings, right? I think everybody's comfortable saying that gut feelings got a lot of people in trouble seven, eight years ago.

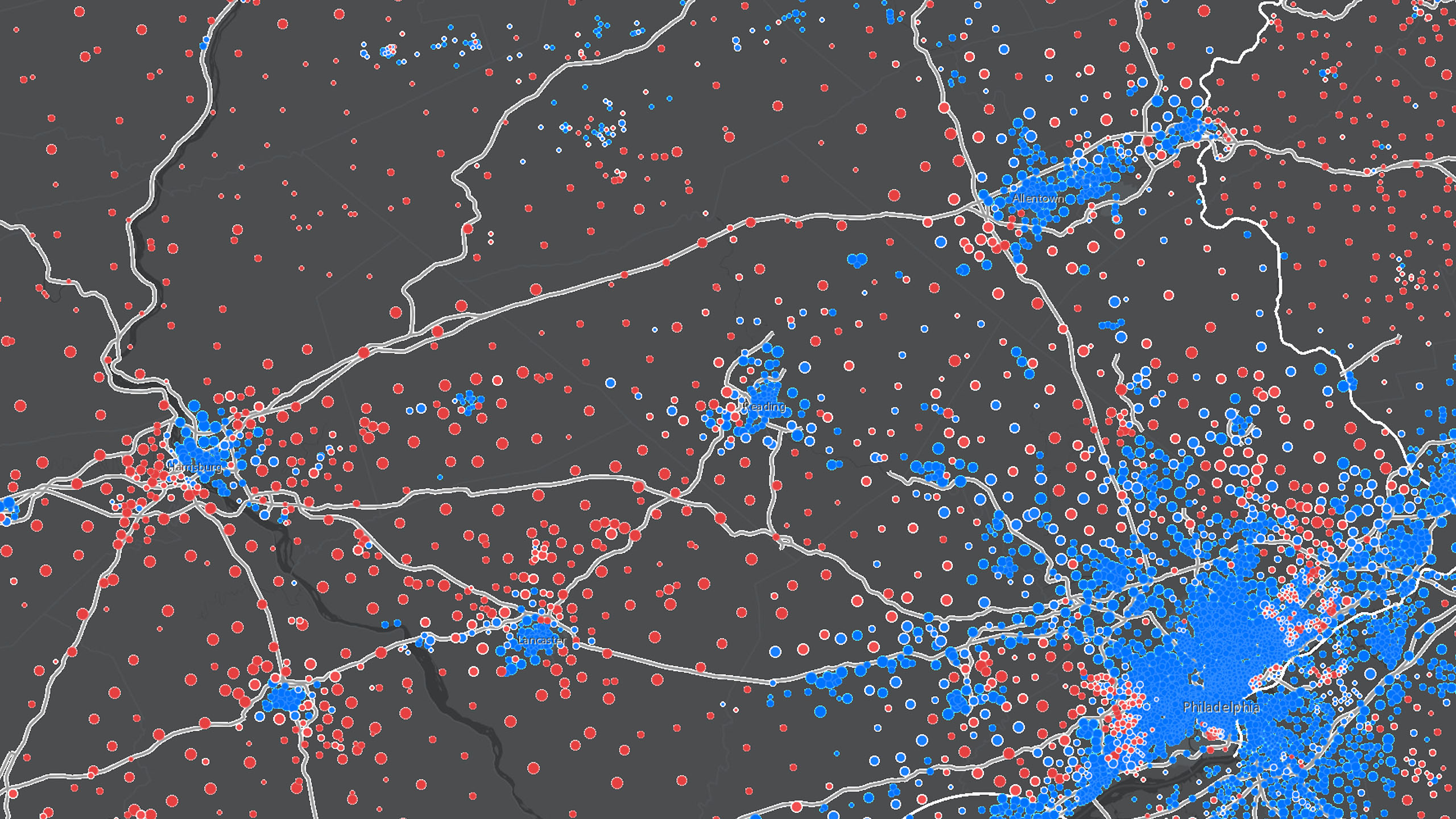

The introduction of GIS—a technology that has existed for decades but is gaining a following in new industries—changed all that. Now, as American Banker noted recently, banks are scrambling to hire tech-savvy professionals who can create and analyze digital maps with multiple layers of data—loan rates, levels of homeownership, spending habits, and more.

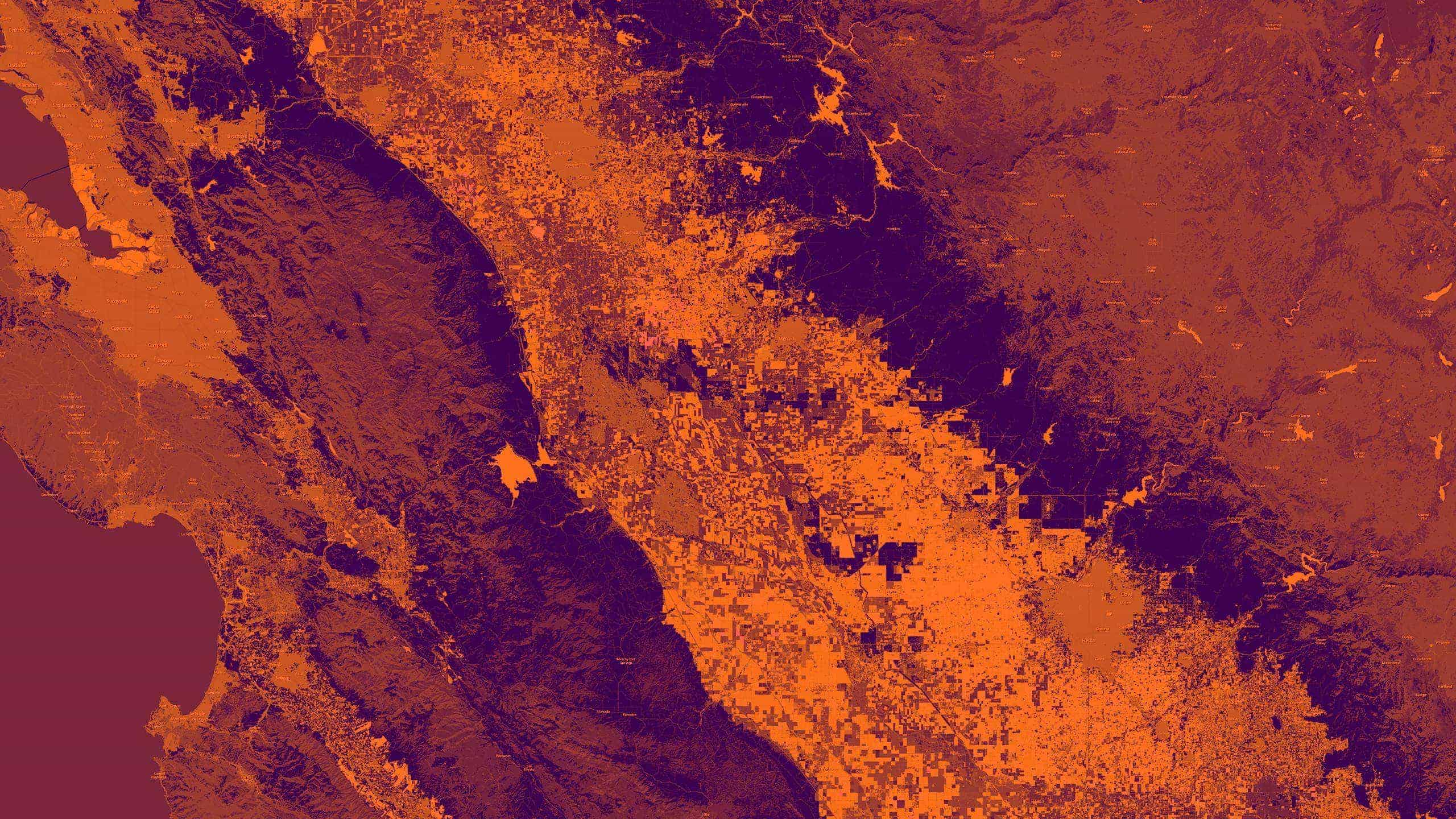

At Regions, location analytics technology allows the branch-siting team to ensure that the bank is serving underbanked communities, while keeping an eye on internal performance and external competition. The team uses digital maps layered with low- and moderate-income census tracts and other key data to run scenarios that measure the impact of opening or closing a branch. The scenarios quickly reveal whether a change would reduce service in needy neighborhoods.

“In the past, you had to dedicate a person to doing a three-week process to get a map, or a two-week process to do analytics,” says Grant Mullins, who leads the Spatial Intelligence team at Regions. “Now we are able to automate and streamline so much; you don’t necessarily have to have a big team to do big team analytics.”

Analytics Illuminates a New Path

Although the Spatial Intelligence team was created to focus on risk management, the potential of GIS to help Regions reach the unbanked and underbanked quickly became apparent. Soon after Mullins joined the company, its headquarters, in Birmingham, Alabama, hosted a meeting of Regions’ mortgage loan officers (MLOs) and management staff from across the country. The goal was to strategize how the bank could be a better neighbor: providing services to more of the underbanked, marketing a wider variety of mortgage products, and making the right loans in the right places.

At the time, Regions’ MLOs might spend a full day researching 20 prospective mortgagees—painstakingly combing through five or six websites and data sources to create a profile of each potential customer and then finding financial products that matched their needs and qualifications. The Spatial Intelligence team built a digital map layered with all the necessary data points, so MLOs could simply drag a spreadsheet of 20 addresses onto the digital map and instantly get a report on the whole batch.

It turned out that one of the best ways to do good in the community and do well on the bottom line was to simply speed up the process. MLOs can now quickly match affordable financial products to customers who qualify while also providing higher-income customers with a faster response.

The maps remove a lot of guesswork and provide concrete measures of shared value.

Originally formed to support risk management, Regions’ Spatial Intelligence and Location Analytics group now delivers location intelligence to support decision making across the company.

“Without the technology and without the science to back things up, you become dependent on essentially gut feelings, right?” Mullins notes. “I think everybody’s comfortable saying that gut feelings got a lot of people in trouble seven, eight years ago.”

Regions is not the only bank that sees the business benefits of being a good neighbor. Peter Scher, head of corporate responsibility for JPMorgan Chase, recently told Fortune that community investment certainly feels good (and helps retain top talent), but it isn’t charity—it’s good for the bottom line. For example, since 2014, JPMorgan Chase—with help from a location-based database to drive decision-making—has invested more than $50 million in community development-focused financial institutions in Detroit. The bank’s Invested in Detroit initiative has created or preserved nearly 1,700 jobs, financed about 100 new businesses, and reached some 15,000 people through training programs, Scher’s team said. And it also has delivered financially for the bank, with $8.9 million to date repaid and not a single default.

Ensuring Compliance

At Regions, Mullins and his team were originally hired to monitor risk, and that continues to be a big part of what they do. All banks must comply with the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), which was passed by Congress in 1977 in part to combat redlining, “a practice in which a mortgage lender denies loans or an insurance provider restricts services to certain areas of a community, often because of the racial characteristics of the applicant’s neighbourhood.”1

As American Banker noted recently, banks are scrambling to hire tech-savvy professionals who can create digital maps with multiple layers of data—loan rates, levels of homeownership, spending habits, and more.

Noncompliance can tarnish a bank’s reputation—and bring business growth to a standstill. When a bank falls out of compliance, the federal government freezes all acquisitions and expansions, which is what happened to Regions in late 2015. Regions discovered that it had erroneously charged $49 million in overdraft fees. On its own, Regions reimbursed customers and reported the issue, but nonetheless, its CRA rating was lowered to Needs to Improve. Expansion plans for 2016 were paused for three quarters until the rating could be raised.

Perhaps partly because Regions self-reported the issue and partly because of the bank’s commitment to serving its communities well, in 2016 Regions had the best overall reputation among top US banks and the best reputation among customers for the second year running, according to a survey from advisory firm Reputation Institute and American Banker. And this year, Regions was named a Gallup Great Workplace Award winner for the third year in a row.

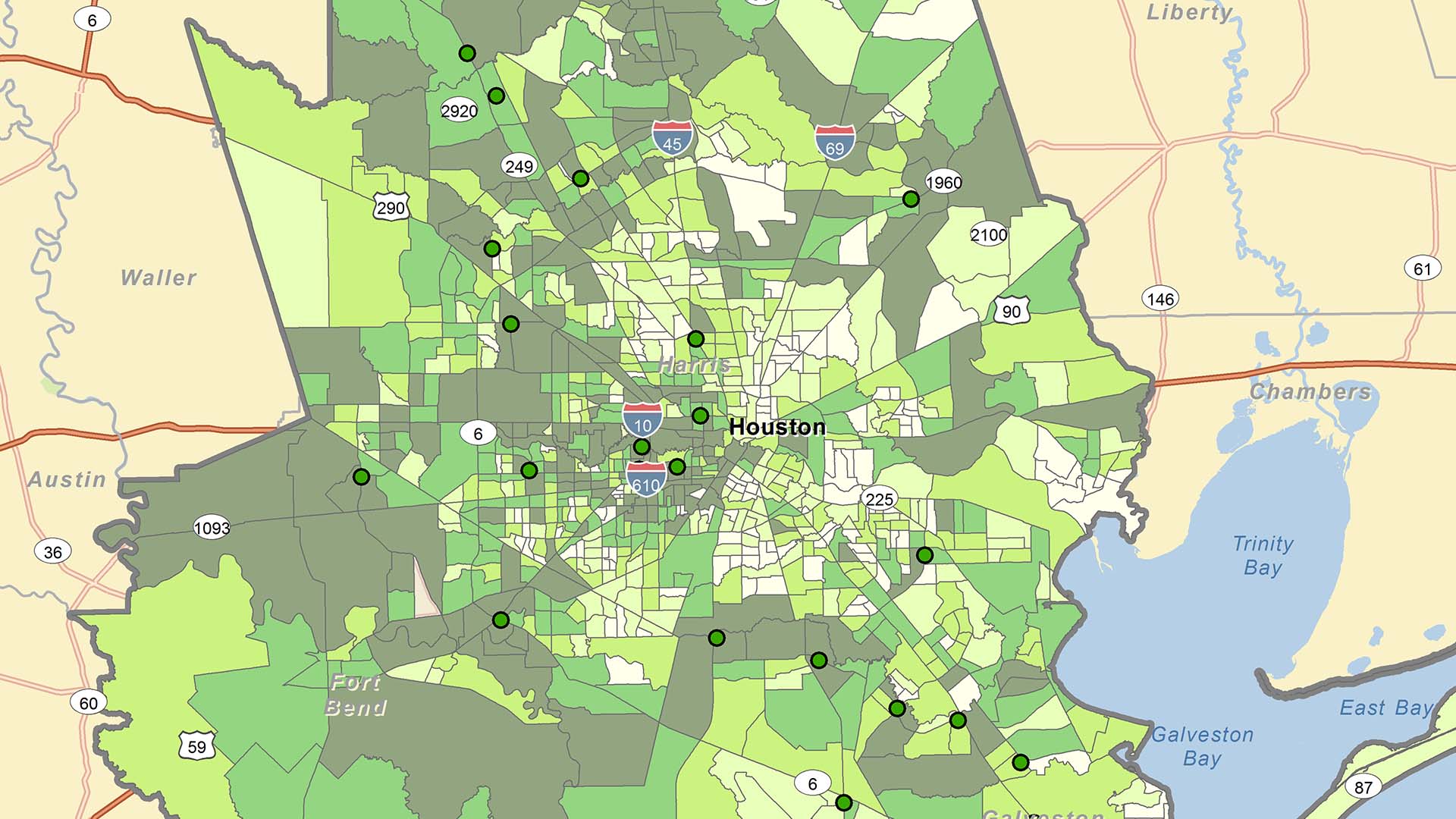

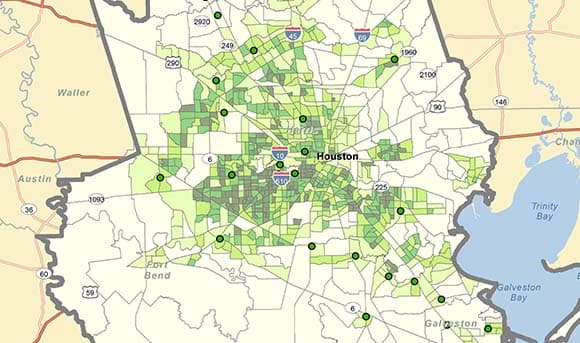

In 2014, the bank had dealt with a different kind of compliance issue—and an erroneous one at that—but its use of location analytics brought clarity, precision, and a fast resolution. A CRA complaint was filed accusing the bank of redlining in a low-income area of Houston. Regions plugged the location information into its GIS software and discovered that the complainant was correct: no residential loans had been made in the tract in question. The reason? The location consisted of polluted brownfields, not homes. (See map at right.)

“It was apparent really quick that that was industrial wasteland. There was no one there to loan to at all,” says Lamar Jeffries, Regions’ CRA administrator. Responding to the complaint was quick work as well. “A map and a short write-up of your slide and, boom, you’re done,” he says.

‘We Can Do Both’

More often, however, Regions and other banks are using the capabilities of location analytics to quickly match lower-income customers with affordable products and ensure that bank branches serve neighborhoods that might once have been ignored. Digital transformation may, in fact, be helping the industry become more consumer centric by personalizing financial offerings for both low- and high-income customers.

“I think if you harness the technology to really understand your customer, understand where you’re operating, understand what makes your business good, I think you can do both. I think we can do what’s right for the underbanked and stay in areas that don’t have a lot of options and still grow our business,” Mullins says. “I think Regions as a bank has proven that.”

References

- Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/redlining