As a store detective in the early days of his career, Read Hayes never would have guessed that he’d someday gather executives around digital maps to study patterns of retail theft. Back then, he placed metal pins in paper maps, hoping to understand whether merchandise was disappearing from certain store departments more than others.

After several years in loss prevention, Hayes earned a PhD in criminology and founded the Loss Prevention Research Council in 2000 with 10 major retailers. Today, the group numbers almost 70, and Hayes has left the paper maps far behind. The council uses modern geographic information system (GIS) technology to detect patterns in retail crime and give retailers the operational awareness they need to keep products, employees, and customers safe.

“It’s a way for everybody to gather around the table with that kind of mapping to . . . think about these [events],” Hayes explains. “Why are they happening here and not here?”

Evolving Criminal Trends, from Retail Theft through the Supply Chain

Retail theft has been in the spotlight during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pharmacy chain CVS says in-store theft has soared 300 percent since 2020. That’s just one chain, and shoplifting is only one piece of the puzzle.

Organized, sometimes violent retail crime is also expanding in scope and scale. Prominent, upscale retail brands are increasingly falling victim to coordinated smash-and-grab attacks. Thieves are netting tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of high-end products in minutes, and 86 percent of leading retailers say criminals have threatened store associates. Online platforms and marketplaces provide nearly frictionless ways to liquidate stolen goods.

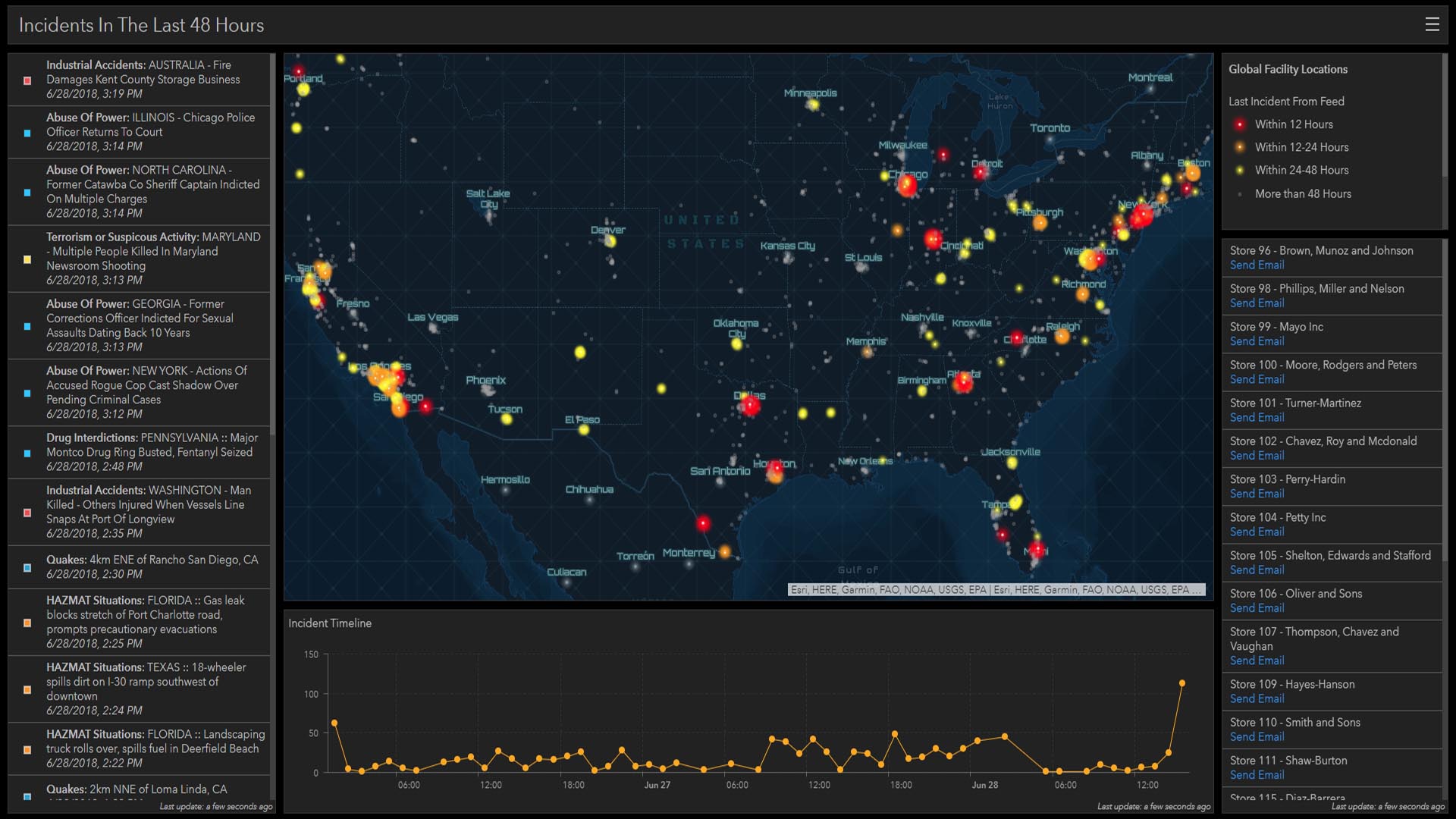

On their own, incidents of retail crime might appear random. But GIS technology is helping to reveal patterns. Indeed, the go-to technology for market analysis and store selection for prominent retailers is now providing operational awareness on retail crime.

“Being able to visualize and identify where clusters of issues are occurring, possible patterns, or how things might be evolving—or if there is some temporal-spatial movement [like] they’re moving from east to west, for example—those are going to be very important,” Hayes says. “That’s where we’re headed right now with mapping.”

As retailers gain operational awareness in and around their stores, other supply chain players are asking a new question: How can we use location intelligence to ensure that products make it to store shelves in the first place?

Using Location Intelligence to Secure the Supply Chain

Although media coverage often focuses on retail theft, securing goods is a challenge at every stage of the supply chain, from manufacturing and distribution to point of sale. Counterfeit goods now account for some 2.5 percent of global trade—more than $450 billion—while cargo theft erases $15 billion to $35 billion from the legitimate supply every year, according to the National Insurance Crime Bureau.

By applying location technology to these issues, organizations can detect patterns and uncover better ways to secure the supply chain.

In one example, manufacturers using RFID tags can log each scan along the supply chain in a geoblockchain. When viewed on GIS maps, a geoblockchain shows an audit trail of a product’s journey from factory to store shelf.

That operational awareness can help manufacturers, shippers, and retailers spot where legitimate products have disappeared from the supply chain and where counterfeit products may have been introduced, pinpointing vulnerabilities in the network.

If a map of recent shipments shows a pattern of goods arriving at their destination port but failing to show up at a particular distribution center, the merchandise team might learn where containers are being diverted. Likewise, if the geoblockchain shows a cargo container leaving its port of origin but not reaching its destination port, that could indicate that goods were lost to inclement weather while on the ocean.

One key to creating this supply chain awareness is embracing technology adept at detecting patterns. For Hayes—who is also a research scientist at the University of Florida’s Wertheim College of Engineering—that means getting closer to the emerging tech that fuels today’s loss prevention work.

He’s now using GIS technology—itself powered by machine learning—in combination with sophisticated AI models, natural language processing, and even robotics to map out and address the retail industry’s challenges.

Maps tend to have a unifying effect. When decision-makers from various business lines visualize supply chain patterns together, they often see where their priorities intersect and how they can address shared issues.

Preparing for Nontraditional Threats, Now and in the Future

Because retailers, manufacturers, and logistics providers have long used GIS software to analyze markets, plan facilities, and create efficient routes, many already have access to a key technology for identifying supply chain vulnerabilities.

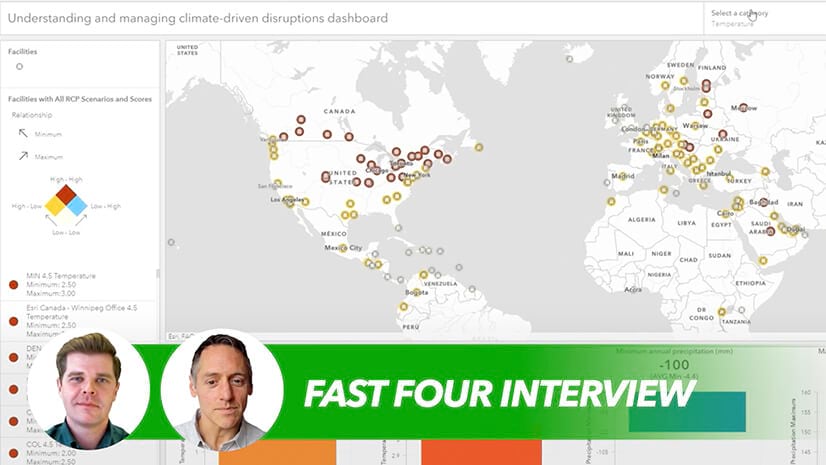

Some are using location technology to prepare for nontraditional threats as well—one of which is climate change. As wildfires, extreme flooding, high heat, and drought increasingly threaten supply chain continuity, some companies are using GIS and predictive models to gauge when and where these factors could disrupt goods in transit years from now.

In today’s supply chain, one innovative combination of GIS technology and smart IoT sensors is creating unprecedented levels of operational awareness. Smart shipping containers—engineered to detect everything from security breaches to elevated levels of CO2—aim to restore confidence to manufacturers, shippers, and retailers by deterring would-be bad actors.

Back at the council, Hayes and team are studying location-based loss prevention techniques in the lab and in real-world retail environments, determined to create a safer environment for goods and people.

Retailers have “physical issues coming at them 24/7 year-round,” Hayes says. “The mapping is going to help us better understand problems, better design and assess the effectiveness of what we do . . . We’re just getting started.”