It happened at remarkable speed, and often with the help of location technology. The COVID-19 pandemic forced companies to adopt novel workflows—some that were already in their infancy prior to the pandemic, and many that will become standard once it subsides.

In one cutting-edge example, a combination of remotely sensed data, AI, and location technology has helped companies maintain customer commitments without putting employees in harm’s way.

In this Think Tank, director of Esri Professional Services Brian Cross talks to colleagues Andrew Leason, head of the imagery practice, and Ed Murphy, insurance practice lead, about what companies are seeing from the skies above—and how they’re using that data to their advantage.

Brian Cross: Andrew, Ed, thanks for joining me for our latest conversation. Clearly, the world has been adapting on many fronts during this pandemic, and those adaptations have triggered some notable innovations. I’d like to explore the changes you’re seeing in remote sensing and imagery.

To get started, let’s talk about the field of remote sensing and how the technology around it is evolving.

Andrew Leason: Remote sensing is a well-established field with a lot of new wrinkles. In its early days, it involved mostly satellite imagery and photography from planes, but now it also includes drones and sensors that measure everything from soil composition to electromagnetic fields, infrared light, and greenhouse gases.

The new frontier combines remote sensing with machine learning, automated image identification, and other AI techniques to help companies see what they might not otherwise be able to see.

Cross: In the context of this pandemic, can you share some examples where a business might have done something in person in the past, and now, by using remote sensing, they can continue operations without putting people in harm’s way?

Ed Murphy: The example that comes to mind is an insurance claims inspector. If a tree falls on a roof, inspecting the damage has always been inherently dangerous. Now you add a pandemic, and the motivation for doing that remotely has grown even more.

We see innovative companies using drones, satellites, or airplanes with high resolution imagery, along with location technology, to do some of that work from afar. And they’re at an advantage because they don’t need to put people in the field, and they can still respond to clients’ needs.

Lockdowns and the need to minimize human movement and interaction inspired the use of technology to maintain business continuity and serve customers in new ways.

A Growing Role for Artificial Intelligence

Cross: For companies and emergency responders who want to assess situations without putting boots on the ground, can you give us a glimpse into the technology making that possible?

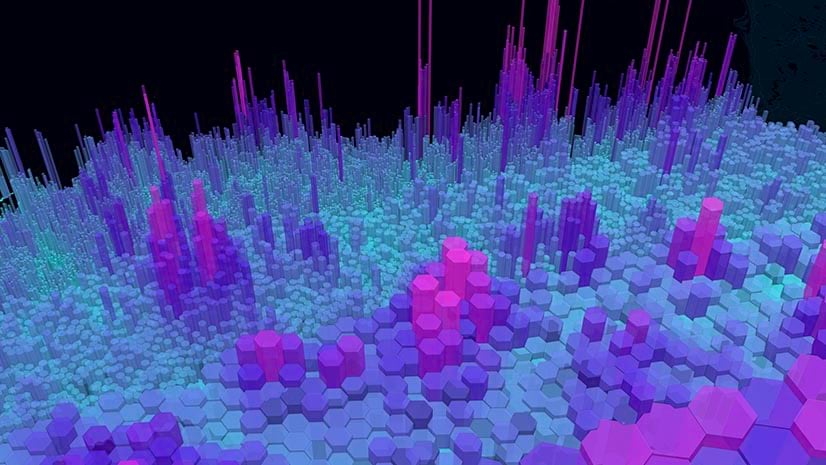

Leason: With the new generation of small satellites, aerial flights, and drones, there’s a deluge of remotely sensed data available. That volume of information can’t be handled by a person looking at a screen. AI models are helping analyze that information and extract meaningful insight quickly—like being able to assess damage to a home so the company can deliver a payment to the customer even before the customer is allowed back in their home.

Cross: What does this workflow look like? Are people not involved at all?

Leason: These systems are not infallible, so people are involved. But instead of an analyst flipping through images one by one, the AI system basically analyzes the images upfront and queues them for the analyst to verify. That means a person can go from processing a small area to processing a very large area in less time.

Murphy: That certainly applies to field operations and response, but we’re also seeing companies use remote sensing earlier in the customer life cycle. If we stay with the insurance example for a minute, AI models are learning to distinguish between trampolines and pools to help insurers assess the risk of underwriting a property. Behind the scenes, a geographic information system [GIS] connects the imagery to a specific location or street address. Geography is the foundation that ties it all together.

Innovation in Energy, Engineering, Construction

Cross: Outside of insurance, where are you seeing innovation in remote sensing?

Leason: Oil and gas companies have gone through some financial upheaval recently, so they’re looking for additional ways to improve efficiency. Some are diversifying their portfolios to include renewable power sources, and they’re using remotely sensed data to review potential sites for wind and solar energy projects and transmission corridors to distribute the energy they generate.

Companies that transport commodities like oil, gas, water, power, even freight—they’re required to monitor what’s happening along those corridors. Most don’t have the staff to scan hundreds of miles for things like leaks, vegetation encroachment, or faulty equipment. We’ve worked with companies to fly a drone or aircraft along a large section of the easement, then deliver the results to a cloud-based AI system to help operations managers spot issues. Train companies are doing similar work using lidar sensors attached to train cars.

We’re also seeing innovation on infrastructure projects—companies using drones to map a construction site and track daily progress, for example. When you collect images regularly, you create a kind of temporal digital twin that allows you to see how operations and projects have changed over time.

COVID-19’s Accelerating Effect

Cross: This technology and these approaches existed before COVID, and more progressive organizations were already starting to use them. But it seems that COVID became a forcing function, and many organizations sort of made it over the edge because of that.

Murphy: When the pandemic hit and the rules of employee safety changed for most companies, executives had to think differently about how to operate responsibly and efficiently. The pressure from COVID drove this combination of technologies into the mainstream quickly.

Leason: Neural networks have been around for nearly 30 years, but today, the power of computing, the use of the cloud, technologies like Kubernetes—they’re all advancing rapidly. At the same time, the amount of remotely sensed data is exploding—coming from thousands of sources including satellites, aerial systems, drones, lidar sensors, and more.

Those tech advances are coincidental to COVID, but they’re coming at a good time for companies that want to have eyes on the ground without putting boots on the ground.

The combination of AI, remote sensing, and location intelligence enables operational awareness, helps managers cover large areas without workers on the ground, and delivers insight on key business decisions.

The Lens Expands—AI and Location Intelligence Enlarge the Scope of Awareness

Cross: Andrew, you’ve been working on a project applying artificial intelligence to remotely sensed data, but at a scale that was unheard of just a few years ago. Could you share what that involves?

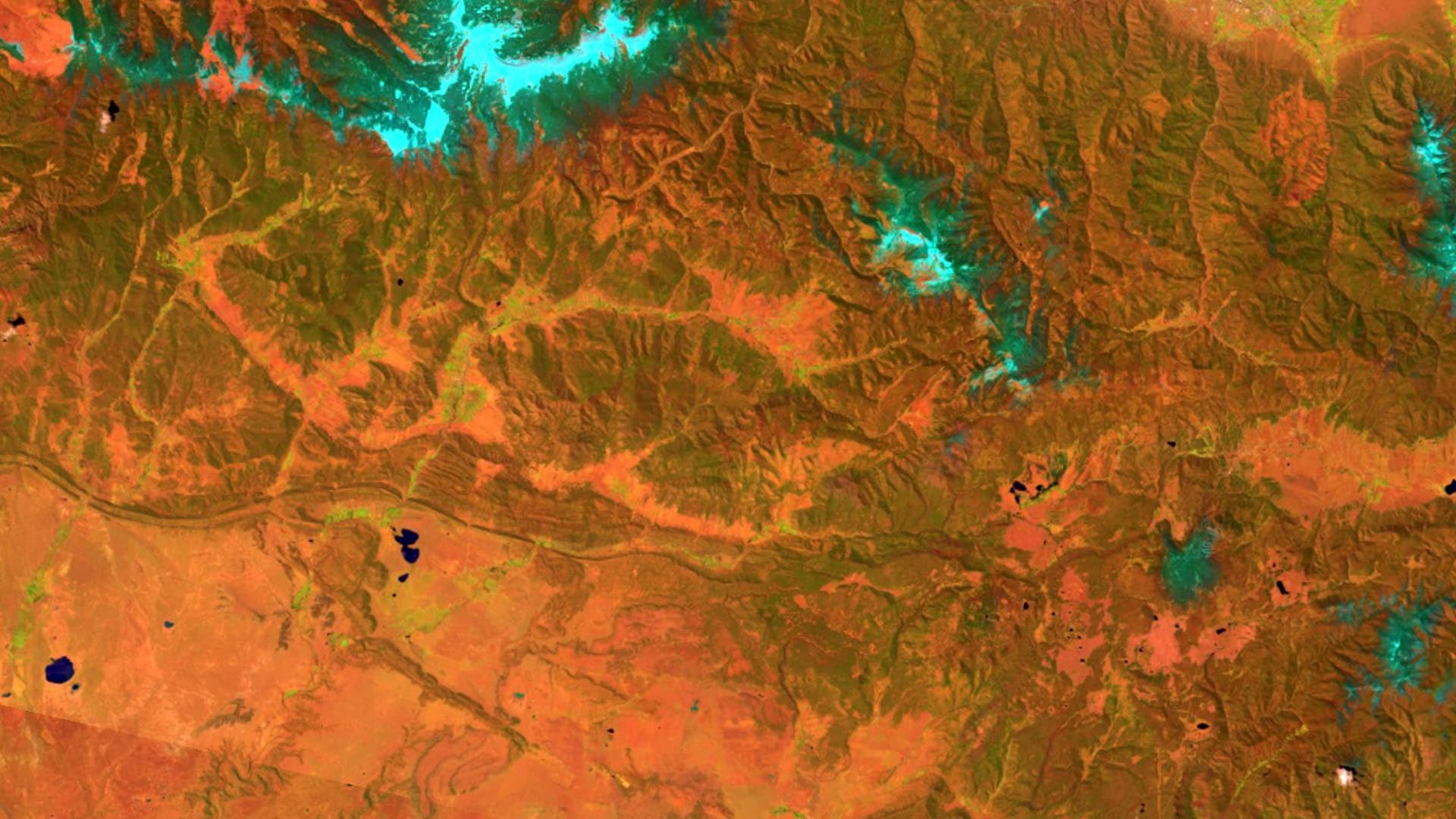

Leason: For years, we’ve led projects where we used imagery to identify tree species in a certain area of a forest, for example. But in this project, we combined imagery, AI, and location technology to determine the species makeup not just of a state or even an eco-region but of the continent. That scale is only possible because imagery resolution is improving; AI models are getting smarter; and location technology runs on more powerful computing, which boosts its analytical capability.

And part of that work involves analyzing the carbon stock of the country. That’s a growing area of focus for companies, governments, all kinds of organizations—they’re more interested in sustainability every day. When you’re talking about challenges like climate change, you need large-scale awareness to understand where we stand and how we can make the most impact.

Cross: The idea that remote sensing and AI are accurate enough and scalable enough to process the entire nation and give us a holistic view we’ve never had—that’s quite a breakthrough.

Leason: And it’s not just geographic awareness—it’s also awareness across time. We can compare today’s imagery with imagery from 5, 10 years ago and more, and better understand changes across the national landscape. That kind of remote sensing applies to industries like agriculture, ranching, and viticulture that are interested in large-scale surveillance, as well as any industry that’s working on its carbon footprint.

Murphy: Something similar is happening in insurance—companies are looking at portfolios at massive scales now. If we have an insurer with 25 million policies who can use imagery to track daily events, that’s a pretty powerful tool for operating efficiently at scale.

How to Get Started—Building on Existing Location Intelligence

Cross: A lot of readers might be saying, “I run a business or an operation, and this is interesting—but how do I actually apply it to my business problem?” Ed, how do you see organizations applying this new blend of technology to their operations and decisions?

Murphy: Successful businesses focus on a couple of things. One is, while this can be seen as exotic tech, it’s important not to create exotic capabilities in the organization. We’ve found that successful organizations build on existing initiatives. They might already use GIS-based mapping somewhere in the organization, and they’ll add this as a new capability rather than creating an exotic hobby for the company.

A second thing is, they’ll identify a real business problem up front—like the need to send workers out to evaluate the condition of a pipe. Can that be done with remote sensing? If you can solve that smaller problem with location intelligence, AI, and remote sensing, then you start to understand what it takes, what the trade-offs are, and what’s possible.

Where Next—AI Classification across Geographies

Cross: We’ve already touched on recent advances in the technology, but what’s ahead for it, and how will that affect business processes?

Leason: One capability we expect in the near future relates to the way AI models classify remotely sensed data like imagery. Today that’s mostly done one scene at a time, but the goal is to be able to tell the AI model to find houses in South Carolina and California, for instance, without it failing because one area is forest and one is desert. If we can start to use this technology not just at scale, but across a large variety of landscapes and environments, then we’ll be even more efficient.

Murphy: It’s also not far-fetched to expect that the convergence of cloud computing, AI, and location technology will start to contribute in real time or near real time. Imagine an organization that tracks all its vehicles, and also operates drones running an AI program that automatically detects certain conditions in real-time imagery. A drone might spot a damaged building or a field of crops with low water content. At a computing center in the cloud, the imagery, AI workflows, and workflows for mobile workers converge in near real time. The drone might alert a vehicle to divert and check the event before the driver’s shift ends, instead of putting it in queue for tomorrow’s work crew.

From what we’ve seen in several industries, that future is not so far off.