Along Spain’s northern coast, where the Cantabrian Mountains meet the sea, lies a region that draws millions to its beaches, forests, and historic towns. But the popularity threatens the landscape it celebrates.

Gabriel Ortiz and his team of five cartographers at Cantabria’s regional government, map this beloved landscape—serving as both guides and guardians. Using computer vision trained on decades of aerial photos, they see what others can’t: which beaches will overflow on summer weekends, where invasive grasses are spreading, where forests have doubled in 60 years.

“We are constantly using AI to make society aware of the problems and why those problems happen,” Ortiz said. Their maps and data-driven analysis guide visitors and help officials protect fragile places from overuse.

When COVID-19 raised concerns about crowded beaches, Ortiz’s bosses asked for a map. He counted the people instead.

Training AI to detect beachgoers in aerial photos was difficult – people appear as faint shadows, barely distinguishable from towels and umbrellas. His team labeled images and taught the model to recognize patterns across five aerial surveys from 2002 to 2017.

The results changed beach management. On sunny summer holidays, about 76,000 people visit Cantabria’s 104 beaches, but the distribution is uneven. Eastern beaches like Brazomar and Sardinero carry the heaviest crowds, while western beaches like Gerra offer similar beauty with far fewer people.

“If you are looking for a natural and less crowded beach in Cantabria, consider Gerra,” Ortiz’s team notes in their beach analysis. The pressure maps guide visitors to make smart choices while protecting fragile spots. Small popular beaches face the greatest stress—a tiny beach packed with people suffers more damage per square meter than a large beach with double the crowds.

The model weights usable beach area: dry sand counts fully, wet sand 50 percent, dune systems 10 percent, and rocky areas 5 percent. This reveals environmental pressure per square meter based on each beach’s composition.

Beyond counting beachgoers, the team analyzes where vehicles cluster—often in sensitive coastal areas—to identify where better public transit could reduce damage.

Ortiz’s vehicle detection models reveal troubling patterns: thousands of cars parked in grasslands turned into makeshift lots, and campers in areas never meant for them.

The maps suggest solutions. By pinpointing popular spots and transport bottlenecks, officials can plan routes that serve visitors while protecting sensitive areas. Where should new bus routes go? Which parking areas need management? How can visitors reach beaches without damaging the landscape?

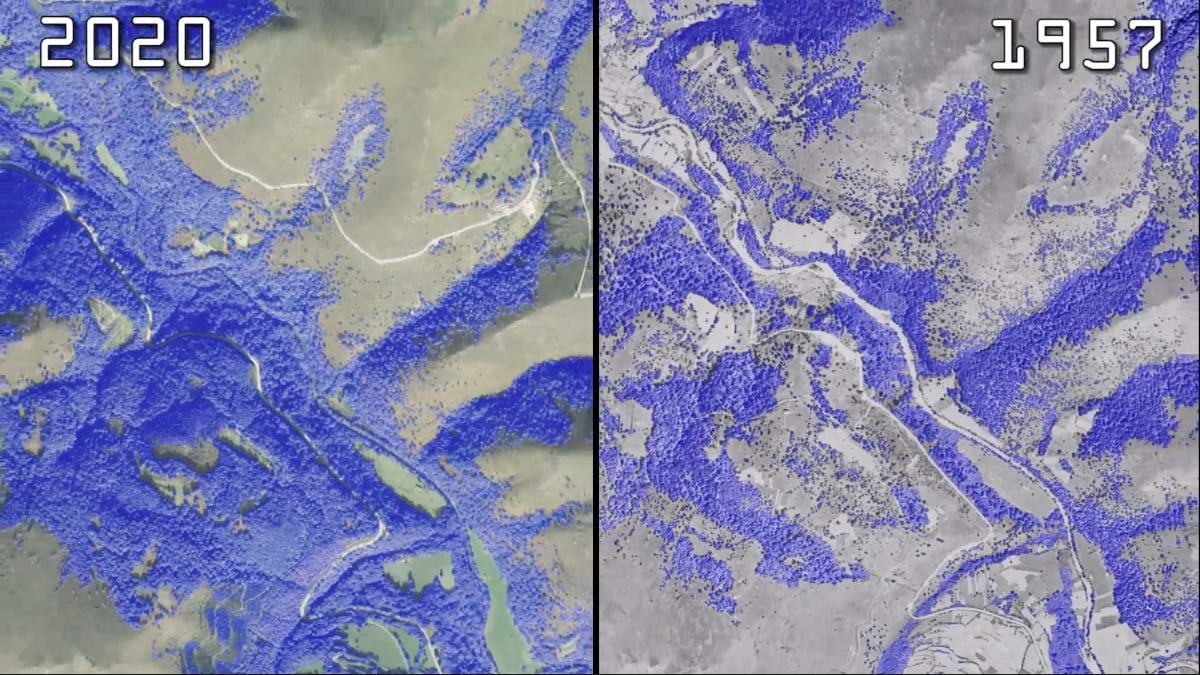

The team’s most surprising discovery: forest cover more than doubled between 1957 and 2020. Unlike global stories of deforestation, Cantabria’s forests recovered.

“This is not an opinion. This is what is really happening,” Ortiz said, highlighting the yellow areas on his maps showing vegetation gains far outweighing losses in red.

The change reflects social and economic shifts. As people abandoned farming and moved to cities, marginal agricultural lands reverted to forest. Industrial eucalyptus plantations expanded, but native species also thrived. The landscape is dramatically more forested than in the 1950s.

National officials confirmed the findings matched broader trends, though without his model’s resolution. The analysis shows forests can recover when human pressure shifts—and highlights the urgency for managing that growth.

Not all vegetation growth benefits the landscape. Pampas grass, an aggressive South American species, spreads rapidly across European Atlantic coast, crowding out native plants and creating health hazards. Traditional surveys couldn’t track its spread across Cantabria’s 533,000 hectares.

Ortiz’s team trained models to detect pampas grass in aerial photos, giving conservation groups precise, updated maps of where to focus eradication efforts.

“We created invasive species maps of the whole territory,” Ortiz said. “They are not perfect, of course, but this AI work has just started. In the next few years we will witness more and more advances in this field.”

NGOs now use these maps for field operations, replacing expensive manual surveys with automated analysis. The approach shows how AI can track fast-spreading invasive species at landscape scale.

Ortiz calls computer vision “a force multiplier” that lets his six-person team accomplish what would traditionally require dozens of specialists and millions of dollars. “Every time we will see smaller and smaller teams creating the higher and most important value,” he predicts. “This is going to be the new normal.”

This efficiency comes from choosing the right problems to solve with automation. “Many people try to do crazy things with AI,” Ortiz said. “This technology is excellent, but it’s not suitable for all problems. Choosing the right one and choosing the right strategy is very important.”

Rather than automating everything, the team uses computer vision for tasks impossible for human observers—like counting thousands of beachgoers or invasive species across decades of regional imagery.

Ortiz’s motivation is public service. “I find energy to do all of this because I am serving a bigger purpose, which is creating a better society.”

That philosophy shapes their data sharing. Unlike organizations that guard datasets, Cantabria makes everything open. “This data belongs to the taxpayer. It’s not our information,” Ortiz said.

The team’s mobile mapping apps put decades of territorial analysis into citizens’ hands. Since 2016, the apps have become part of daily life, allowing residents to access datasets anywhere in the region.

Their ArcGIS StoryMaps stories combine analysis with accessible explanations. “One image has much more power than 1,000 words,” Ortiz said. “When you publish something meaningful in a StoryMap, people can interact with all the data. You can really tell stories and connect with people through them.”

Ortiz is planning Cantabria’s next projects: digital twins that capture lifelike 3D replicas anyone can explore intuitively, achieved with minimal cost (see sidebar).

“Digital twins are the next evolution in cartography,” Ortiz said. “For centuries, we have been using projections to simplify reality to a flat canvas, to a paper map. But as digital technology evolves, the world doesn’t need to be projected anymore. We are going to be able to reflect reality with less demanding abstractions. We will be able to create lifelike replicas of our world.”

Traditional maps require specialized knowledge to interpret. Digital twins let citizens explore their landscape naturally. “When you see something in 3D, it’s easier to understand for the average citizen than seeing a technical map full of colors and symbologies,” Ortiz said.

This accessibility could transform how people participate in land use planning.

As digital twins evolve, these tools could guide visitors in real time—helping them find uncrowded coves and forest trails while protecting fragile places. Everyone could see Cantabria through the eyes of those who know it best, experiencing the landscape with less pressure and more wonder.

Learn more about how national authorities apply GIS to modernize mapping to collaborate and make more informed decision for the future.