In 2020, California governor Gavin Newsom put into play the most aggressive clean-car act in the US, an executive order that would effectively eliminate the sale of gas-powered vehicles in the state by 2035.

A shift of this magnitude would require California to have close to 1.2 million shared and public electric vehicle (EV) charging stations on roads by 2030, according to an analysis by the California Energy Commission. Therein lies the rub: Fewer than 75,000 EV chargers have been installed to date.

Government officials, utility companies, and residents need innovative strategies and cutting-edge tools to close that gap. One such resource recently emerged from a partnership among design consultancy firm Arup, California utility providers, and the Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator (LACI). Together they created a web-based site-suitability tool for EV charging stations called Charge4All. Using geographic information system (GIS) technology, the program analyzed data on transportation and energy networks, demographics, and EV adoption to identify areas where EV chargers will be needed as adoption increases.

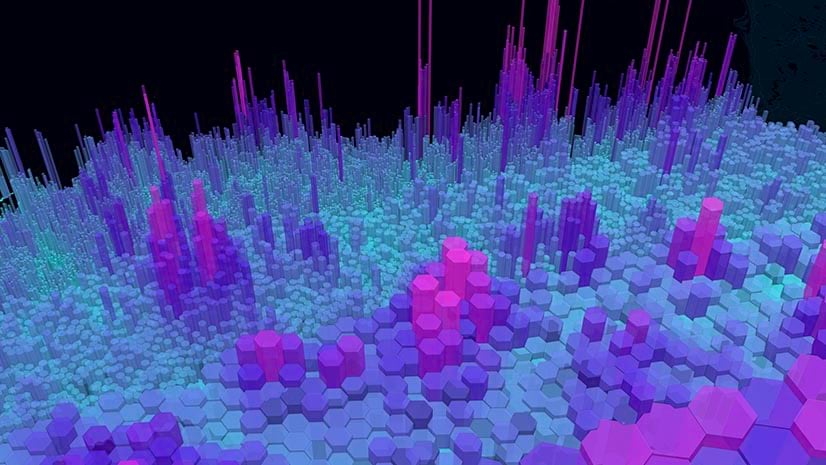

The Charge4All dashboard was created as a decision-support tool for elected officials, utility executives, and local communities—giving them color-coded maps with which to determine the most efficient—and equitable—locations for EV chargers in Southern California.

Taking the Higher Road to Deploy EV Chargers

Past efforts to site charging stations have primarily emphasized traffic levels and existing EV adoption patterns. Arup and its partners broadened their EV charger analysis to include economically disadvantaged neighborhoods—an acknowledgment of how widespread EVs are likely to become.

“We wanted to make sure that equity was addressed and that it was at the forefront of the development of this tool,” says Samantha Lustado, a senior geospatial analyst at Arup who helped build Charge4All using 45 gigabytes of data and the analytical capabilities of GIS technology.

Green energy companies and utilities are increasingly turning to GIS to guide strategy and infrastructure decisions by contextualizing key information streams, including equitable access. Lustado researched and incorporated 20 datasets to determine site suitability for EV chargers, including population density and proximity to places of interest.

As Katherine Perez, Arup cities leader and the project director for Charge4All, explains, “We thought we were improving on something, but we realized we were actually creating a true pilot.”

Through Charge4All, investors, executives, and government decision-makers can take a county-level view of priority regions for EV charger distribution. The tool allows them to analyze factors like the concentration of multiunit dwellings—where fewer at-home chargers exist—as well as socioeconomic trends. With GIS smart maps, users can zoom in and determine site suitability at the curb level, accounting for road types and proximity to electrical infrastructure.

The detailed street view could save organizations hours of time and cost associated with in-person inspections of potential charging sites. Instead, a city or energy company can filter out or prioritize sites before making a field visit.

For something as physically small as a charging station, the idea that you could use geospatial analysis to drill right down to that level—that the data would ever be good enough—is really quite unusual.

Making a Difference with a Map

For LA native Lustado, the project was a fulfillment of her professional goal to use GIS to reshape the world for the better.

The daughter of Filipino immigrants and an activist for LGBTQ equity, Lustado was aware of the way that communities can be overlooked by development programs. “Tesla chargers are everywhere,” she says. “But what about those who don’t have Teslas?” Lustado saw the GIS-powered Charge4All app as her way to contribute to a clean energy future from an office chair.

“Being involved in a project like Charge4All and being in the EV space has really shown me that I don’t need to be out there [in the field] to still make that change or to be involved in that sustainability aspect of the environment—that this [work] is completely relevant and quite urgent,” she says.

The Education of an Activist

As a child, Lustado was an inquisitive self-starter. “If I didn’t need help, I would just try and do things on my own,” Lustado says. After she got straight A’s in the fourth grade, her parents agreed to buy her a computer, which she learned how to use primarily by breaking it and putting it back together. It was the dawn of the Internet Era, and the PC offered a portal to the outside world. Working behind a screen was a comfortable place for Lustado—she didn’t want attention, even if she did want to make a difference.

As a freshman at UCLA, she took a biogeography class that sparked her interest in GIS. The ability to integrate multiple datasets from different fields and extract insight suited her interdisciplinary mind. As a budding activist in UCLA’s Filipino and LGBTQ groups, she used GIS data and maps to advocate for marginalized communities. One early map she created plotted LGBTQ-friendly restaurants in the area.

For Lustado, the promise of GIS-powered location intelligence was its ability to unify people and information—the very quality that would later draw her to Charge4All. “It blew my mind at the time,” she says. “I don’t need to just look at biogeography; I can [also] incorporate demographics or sociodemographics.”

GIS can be an incredible tool, particularly in bridging different cultures or languages. It bridges the divide.

Taking the Geospatial Lead

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in geography and environmental studies, Lustado’s first job was in the IT department at UCLA, working on facilities management. From there, she joined a small military contractor, traveling between bases while carrying out field surveys. That led her to the construction management firm Parsons, consulting for the Los Angeles International Airport, before she decided to earn a master of science in GIS at California State University.

Afterward, she applied to just two jobs; one was Arup. Nonhierarchical and employee owned, the company fit her cross-disciplinary approach, as did its emphasis on sustainability and achieving broader social good.

On Arup’s Advanced Digital Engineering team, Lustado was encouraged to share ideas and geospatial thinking with software developers, digital consultants, and data engineers.

When the Charge4All project came across the docket of her supervisor, Roland Martin, he knew Lustado was eager for a new challenge. Martin made Lustado the project’s geospatial lead—the person who would work with colleagues and the project leader Perez to make the technology work.

“I’m not really interested, honestly, in someone who’s a genius who can sit in a back room and whiz away on the keyboard,” Martin says. “I’m interested in someone who can listen to problems, communicate what the problem is, [and] solve it.” That, he says, is one of Sam’s specialties.

The EV charger assignment was Lustado’s first major project, and initially she asked herself, “Can I do this? Do I have the technical skill? Do I have the trust within myself to do it?”

She was heartened by the knowledge that she was part of a strong partnership, and energized by the chance to contribute to a profound societal transition—one that would benefit people and the planet.

Gathering Location Intelligence for EV Charging

As the first major step in the project, Arup and LACI representatives gathered intel from utility partners Burbank Water and Power, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, Southern California Edison, and a number of City of Los Angeles departments including the Bureau of Street Lighting (BSL).

From these conversations, the project team learned about previous efforts to install EV charging stations in the city and heard input from many of the stakeholders who would be integral to the success of a regional push to add plugs.

For example, in speaking with the BSL, Perez, Lustado, and their colleagues learned about a project that involved installing EV charging stations on light poles. Because no companion regulations were established at the time, non-EV drivers began parking in those spaces, blocking access to chargers.

Other initiatives to install EV plugs in the region had moved ahead—without much consultation with local businesses or residents—in an effort to use available funds before time ran out. A number of those EV chargers ended up being vandalized.

By making GIS part of the framework of project management from the start, the Charge4All team could centralize information about neighborhoods and their needs and incorporate insight from actors in the EV space.

“The first generation just kind of had to go out in the market,” Perez says. “Now, we could actually create an informed scenario using maps and all kinds of other accessible tools.”

Sam had to basically unpack all these datasets and pull out the salient information to be able to create the story. That's what she did. She owns that piece of it, and it is the cornerstone. I can't imagine this project absent the dashboard. It wouldn't have been as powerful at all.

A Clean Air Future for Everyone

Once the Arup team had an understanding of the principles and priorities that would guide an equitable approach to EV charging sites, the next step involved data hunting—a stage that Lustado excelled at, thanks to her perseverance and creativity. She also had to evaluate the data’s quality and determine which datasets would be most efficient to use.

“She found data that I should know as a planner,” says Perez, who says one of Lustado’s best traits is her persistent innovation. “She just kept pushing and pushing, and she would go away and come back and say, ‘I think we’re closer.’ And she’d go away and come back and say, ‘Well, that didn’t work. I’ve got to try something else.'” The GIS analyst’s curiosity about how to refine the tool to its best use was the driver of success, Perez says. “To me, that is the epitome of the combination of passion and skills.”

Lustado says it was also a product of collaboration, and she credits Arup’s Advanced Digital Engineering team for their extensive work on the project.

In thinking about how equity could be incorporated into the tool, Lustado was also considering her own family legacy. When her parents arrived in the US, they didn’t own homes or cars. How would an immigrant living in a multiunit building with limited parking be able to charge an EV? It was an especially urgent question, considering that air pollution has the biggest impacts on lower-income ZIP codes.

Lustado’s GIS analysis revealed some early patterns. Around the more upscale, beachfront Santa Monica area, for example, the team saw high utilization of EVs. In the city’s southeast, closer to downtown LA, they saw a different profile—more neighborhoods with lower incomes, lower levels of vehicle ownership, and less engagement with EVs.

“It was night and day,” Lustado says. Working with transportation planners, Lustado realized that the map-based analysis needed more nuance to reflect many possible users of EV chargers. In another breakthrough moment, she managed to combine nearly 10 different models to make the curb suitability analysis work.

Lustado then formulated a presentation that she would eventually deliver to state agencies, external partners, and other firms curious about Charge4All’s findings. “There was nobody better suited or as articulate as Sam,” Perez says. “She commanded this material.”

Living the Life Cycle of GIS

While Charge4All is currently in beta, eventually any number of cities or regions could adopt the EV charger analysis to help fuel the transition to clean energy transportation. Users will be able to weight criteria and customize the GIS analysis to their region.

For Lustado, completing the Charge4All project was a personal victory as well as a civic one. It brought her out from behind the scenes, summoning leadership skills she hadn’t always known were there. The project also proved that making a difference didn’t have to mean doing everything herself. She learned to balance her independence with the benefits of collaboration, supported by the unifying power of a smart map.

“I think [my career is] kind of like the embodiment of a life cycle of GIS,” she says. “I have the data. I’m now analyzing it.” And she’s working to figure out, “How do I share this, and how do I project manage this? How does this get to the right people to make the decisions that they need to change the world?”