November 10, 2022 |

December 13, 2022

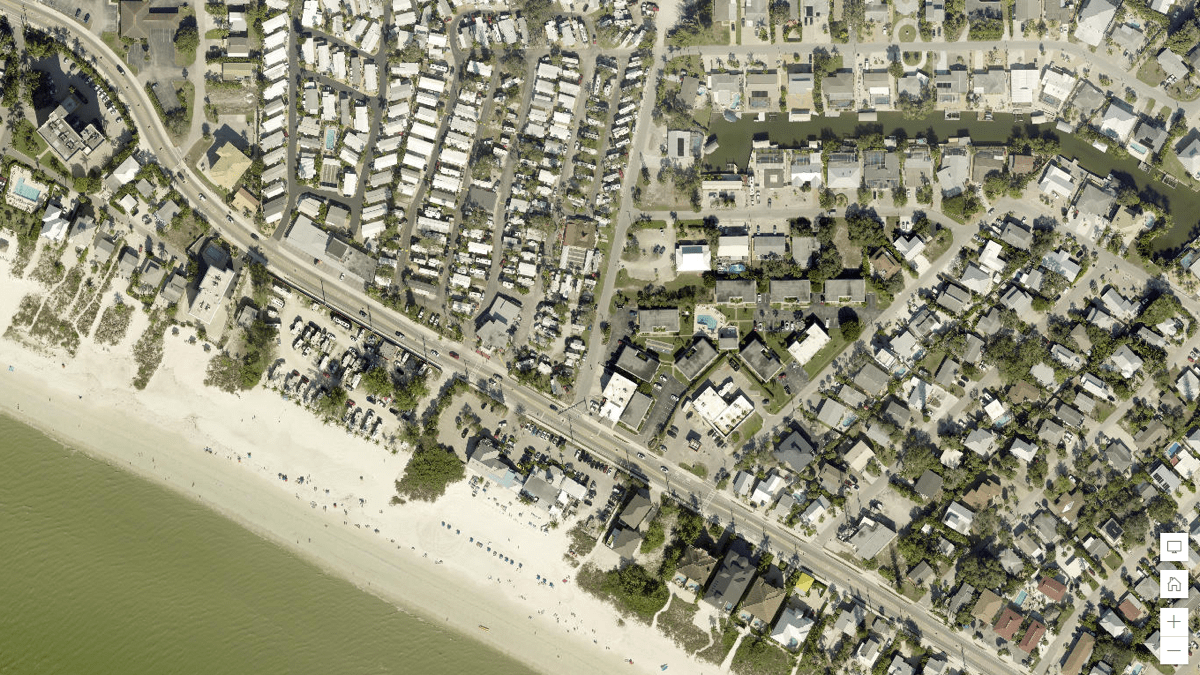

After Hurricane Ian swept through Florida in September, first responders, the US Coast Guard, the National Guard, and Urban Search and Rescue (US&R) teams rushed in, going door-to-door to rescue and assist more than 2,500 people. The category 4 storm reduced many beachfront towns to rubble, and storm surge flooded large swaths of the state.

Thousands of people living aboard boats posed an early concern, because the storm surge coincided with the highest tide that month, and hundreds of boats were pushed deep into the mangroves.

“That kind of search was never done before,” said Mike Zielonka, a captain on Orange County Fire Rescue, Florida Task Force 4 (FL-TF4). “Searchers sent up a drone when they got close to each boat to see if it was even inhabitable. That way we wouldn’t sacrifice a person wading through really hazardous conditions if a search wasn’t needed.”

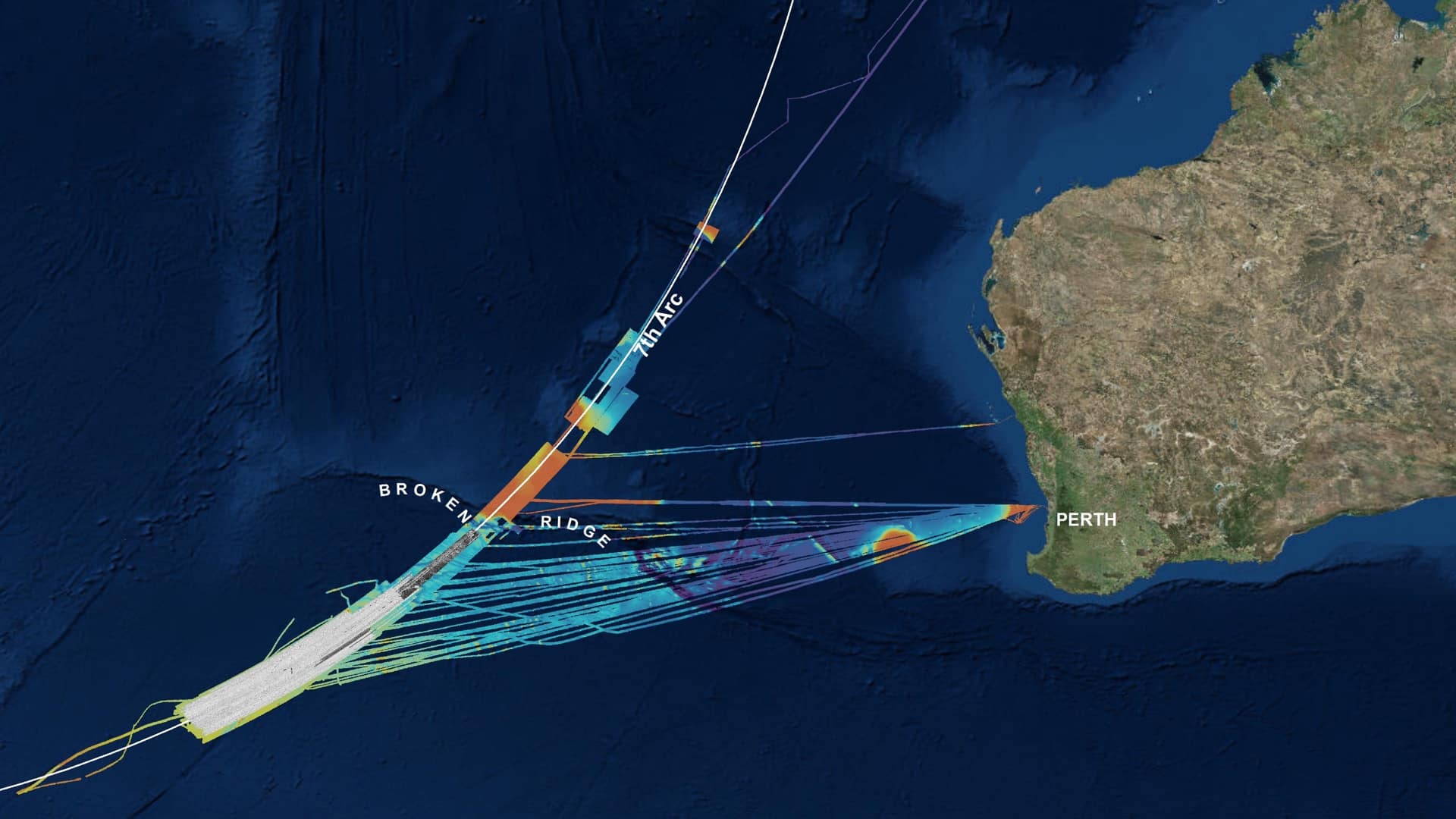

Florida Task Force 4 focused on large liveaboards, ranging from billion-dollar yachts to shrimp boats, conducting hundreds of searches in hard-to-reach places. Zielonka and team used postimpact aerial images to drop waypoints indicating the next boats to search and forwarded a live map to teams that spread out by boat and bushwhacked through mangrove thickets. “The map helped us make sure we covered our bases so we could be very accountable for the areas we searched,” Zielonka said.

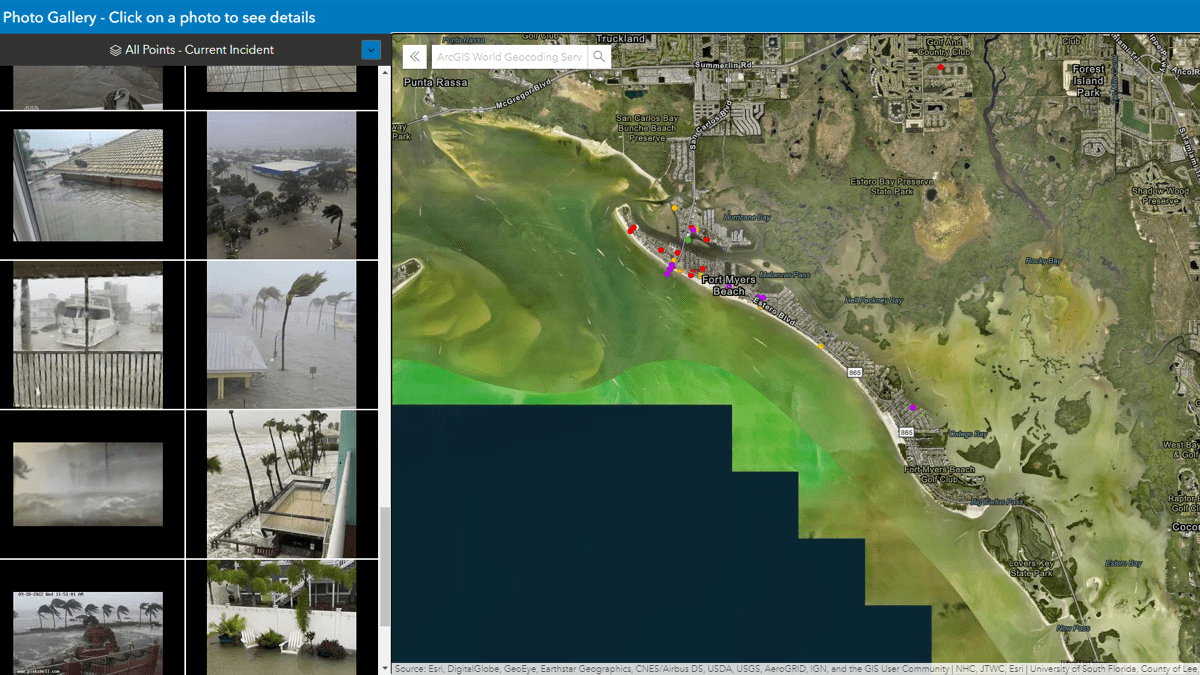

The FL-TF4 team and more than 20 other search and rescue teams used a suite of tools called the Search and Rescue Common Operating Platform (SARCOP) to collect more than 108,000 field observations. The toolset enabled them to segment search areas to be covered in 12-hour shifts, show tracks where each team had been, and drop icons to indicate what was found or done. The situational awareness gave each team as well as coordinators at the state and federal levels the means to stay informed and adjust quickly to cover places where people might be found.

“It made for a better use of teams, not duplicating efforts,” Zielonka said. “I have a long list of the names of the storms I’ve been to over the years, but as far as severely impacted coastal areas, Fort Myers, south Sanibel, and south Pine Island had the most damage I’ve ever seen. The storm wiped the sand clean of structures, leaving behind just piles of sticks.”

SARCOP has been ten years in the making, with a team made up of geographic information system (GIS) practitioners from the National Alliance for Public Safety GIS (NAPSG) Foundation, funding and support from the US Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology (DHS S&T), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and solution engineers from Esri who refined the toolset over the course of many disaster events.

SARCOP takes a people, process, technology approach to search and rescue. It pulls together ArcGIS mobile applications (including Survey123, QuickCapture, Field Maps) and ArcGIS Online in a wrapper built with ArcGIS Experience Builder to capture search and rescue workflows. SARCOP provides a system that’s ready to go, works right away, and is designed for use throughout a wide-area-search incident, such as floods, hurricanes, and tornadoes.

“There have been a lot of smaller deployments, like in Texas where they used SARCOP more than three different times this year for wildfire, tornadoes, and flash floods,” said Paul Doherty, emergency management specialist (geospatial) at FEMA. “Those no notice events are important because there is less time to prepare, so having a common system ready to go really makes a big difference for first responders.”

For Hurricane Ian, Florida’s whole US&R system adopted SARCOP for the wide area search that took two weeks. The local adoption is a key to the success because each disaster starts and ends locally. FEMA coordinates with others and lends support, but it doesn’t lead the response to disasters. Over the years, FEMA has invested in SARCOP and worked alongside the NAPSG Foundation, the International Association of Fire Chiefs, and others to create a common platform to lift up all search and rescue responders who don’t have the ability or funding to build something like this themselves.

Jared Doke, who works closely with Doherty as a program manager for NAPSG Foundation through a grant from DHS S&T, spoke to efficiency gains and how the tool has evolved. “Several years ago, in Louisiana we had a state team and a federal team that were drawing search and rescue segments over each other, going to the same places, and we didn’t know that until the data started showing up,” he said. “Before we had the ability to draw segments on a map, teams were overlapping, not knowing others were there until they’d bump into them on the streets.”

During recent events, with SARCOP adopted by more teams, the search gets done much faster because there’s little overlap.

View this animation to see how the search progressed.

“You can spend a lot of time just asking someone where they are, but when you can see everyone on the map, it removes a lot of that time-consuming chatter,” Doherty said. “Hurricane Ian was a breakthrough for us, because we had, in one map, live tracking of both federal and state teams across a wide area.”

Lexi Passaro deployed to Florida for Hurricane Ian as a Situation Unit Leader on FEMA’s Blue Incident Support Team, which coordinated US&R operations, including strategic and tactical planning. She has been involved with SARCOP’s evolution, using a predecessor tool and then the latest iteration on recent missions to the Champlain Towers building collapse in Florida, floods in Kentucky, and now Hurricane Ian.

“In just a year, it has matured and evolved,” Passaro said. “We came up with an intel cell concept, which is even now maturing into a Search and Rescue Intelligence Group concept. When the data and imagery is combined with human intelligence and remote sensing like unmanned aerial systems images, video, thermal imaging, and other technologies, we can make science and data-based decisions on search planning. The technology has been there for a while, but now we’re getting to use it in more beneficial ways.”

Members of US&R task forces are certified for their skills, such as structural collapse, wide area search, swiftwater rescue, confined spaces, HAZMAT, and other specialties. Passaro relishes her role as a “translator”, to analyze data and information coming from SARCOP and distill it into an informed search plan the Incident Support Team then uses to guide specialists.

“A lot of our members are very skilled at technical rescue, which involves power tools to break and cut concrete, which is really hard hands-on work,” Passaro said. “These are folks who day-to-day are often running into burning buildings, which doesn’t involve computers. They appreciate how easy the tool is to document what they just did, because the data helps all of us. It’s a culture of problem-solving and helping, and just getting done what needs to be done.”

Before Hurricane Ian made landfall in southwest Florida, FEMA’s response geospatial office provided models of where homes might be damaged. The modeled data drives response, knowing where and how many families will need help. It’s also useful for coordinating and clustering search and rescue teams where the most help will be needed.

FEMA’s Tool for Emergency Management and Prioritizing Operations (TEMPO) utilizes the Priority Operations Support Tool (POST) algorithm to provide predictions for areas of greatest social vulnerability, looking at conditions that would cause people not to evacuate, such as non-English language speakers, financial hardship, or lack of transportation.

The US&R teams use this information to plan searches in the hardest hit areas first, to do what’s called a hasty search, moving fast to get people out quickly. Once that is completed, they then go door-to door—this is when the SARCOP map fills in, with first a primary search and then a secondary search to find people who may be trapped.

During the Hurricane Ian response, internet connectivity was supported by the federal program called FirstNet, which supplies mobile telecommunications infrastructure for first responders, and by the satellite-based internet company Starlink. Connectivity ensured response teams could access and make use of photos US&R collected in ArcGIS QuickCapture, as well as other imagery and video captured from drones.

Future goals with SARCOP are to apply a Search and Rescue Intelligence Group concept, using its agile framework to pull data together and see it in different views for different groups.

Another objective is to predict how long it will take to search an area, based on factors such as population density, distance traveled, and severity of impact. This leap will help leaders allocate the right number of resources for the task ahead, whether the mission is in a city or rural area. The ability will build on past performance to know what teams are capable of accomplishing.

Tablets and phones were used on the Hurricane Ian response, and both will continue to be supported for SARCOP. But with GPS and data capture tools in use, better battery charging systems are needed to keep devices powered during dynamic searches. Internet access is key to collaboration and continuing to improve connectivity is a high priority.

The outreach continues with states, cities, counties, and agencies, such as the US Coast Guard, to spread the word about SARCOP and welcome wider participation. The more people who use it, the more effective it can become. With greater information sharing at the outset, the stage can be set for a swifter recovery.

“We’re there for two weeks, mostly to protect and save lives,” Doherty said. “At the end, we package up the information to give it to the local agency to help them plan the recovery. Recovery is the long game, because that will last months and years and we’re happy to help them get off to a good start.”

Learn more about how GIS supports all types of emergency and disaster management operations.

November 10, 2022 |

November 19, 2020 |

March 21, 2018 |