What some might call a great reversal is now under way.

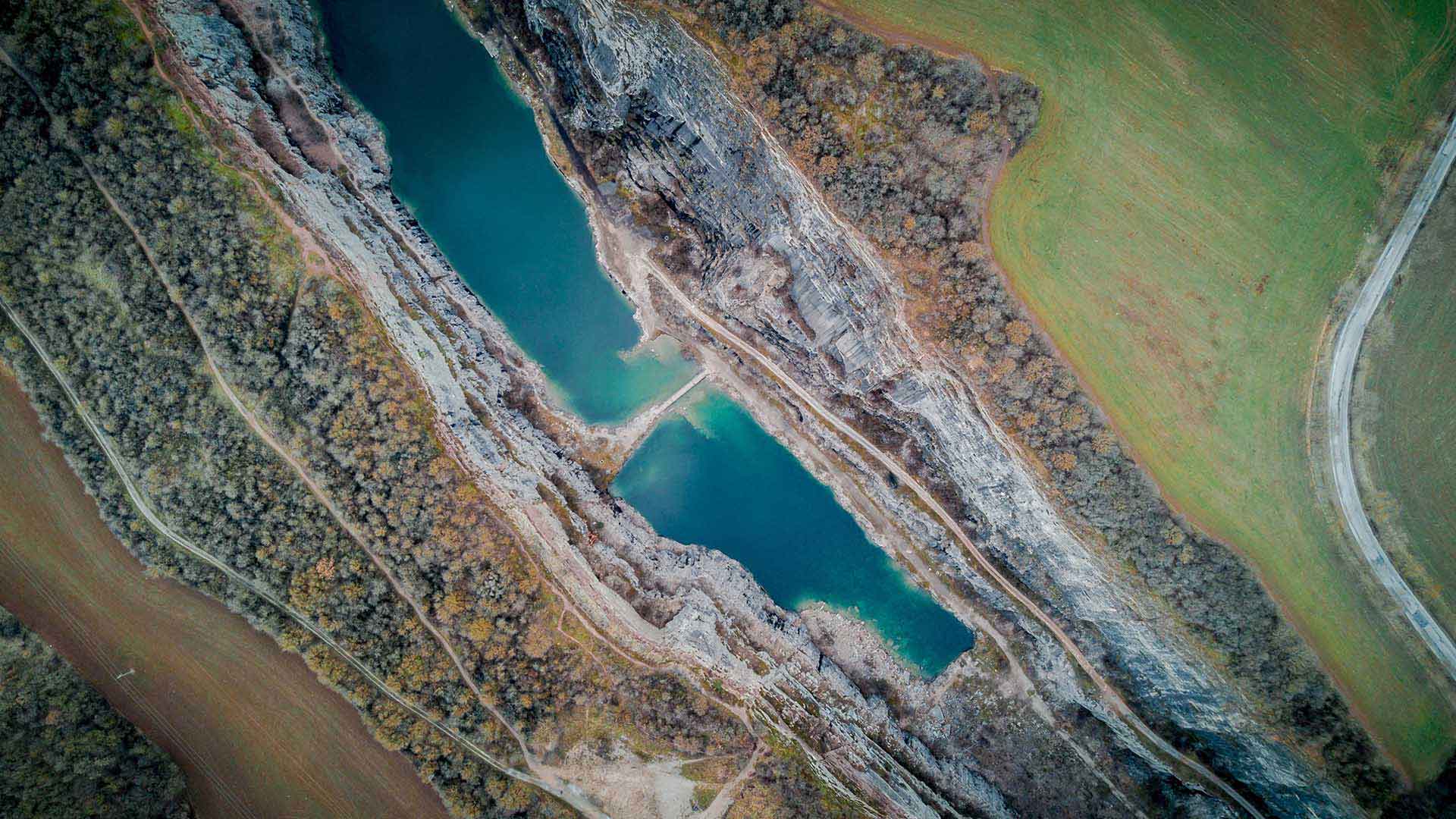

A combined 27,962 miles of oil and gas pipeline crisscross the waters of the United Kingdom Continental Shelf (UKCS)—a powerhouse of petroleum production in Europe. Underwater fields surrounding the UK have yielded over 46 billion barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) since wells were first drilled there in the 1960s and 1970s.

Production in this mature basin peaked in 1999 and, although significant reserves remain to be extracted, it is in managed decline. Yet this mature basin is now in the twilight of its lifecycle, with production having peaked in 1999. Since the UK has committed to achieving net-zero status by 2050, the decline in reserves raises several questions—including what to do with the pipelines and rigs left behind as wells are exhausted.

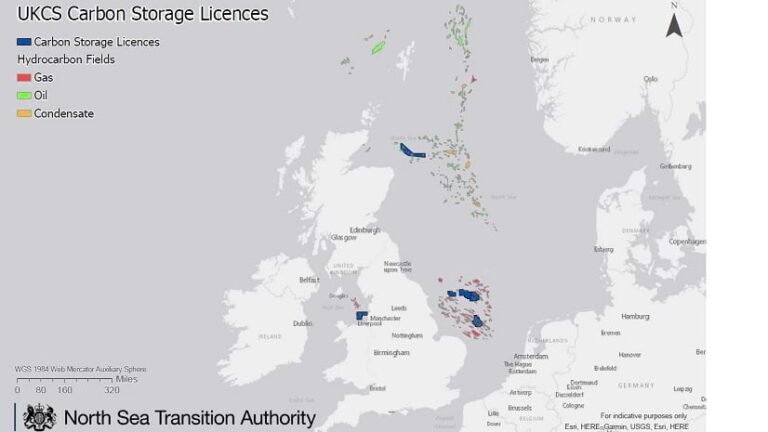

The North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA), which issues licenses for commercial exploration and development of the UKCS, is using geographic information system (GIS) technology to envision a bold second act for this infrastructure.

With approval from the NSTA, companies can repurpose the pipelines that once shuttled oil and gas from seabed to shore, enlisting them to transport carbon captured from onshore operations and industrial facilities back into undersea reservoirs. This innovative public-private partnership could be a bellwether for carbon capture and storage in manufacturing, natural resources, and related industries.

The NSTA’s carbon capture and storage (CCS) initiative shows that the expertise, infrastructure, and capital traditionally dedicated to business activities that produce carbon emissions could now efficiently—and profitably—support a greener future.

The driver is economic, the driver is pace, and the driver is the net-zero target that’s unquestionably set in stone.

Reusing Pipelines and Platforms for Carbon Capture

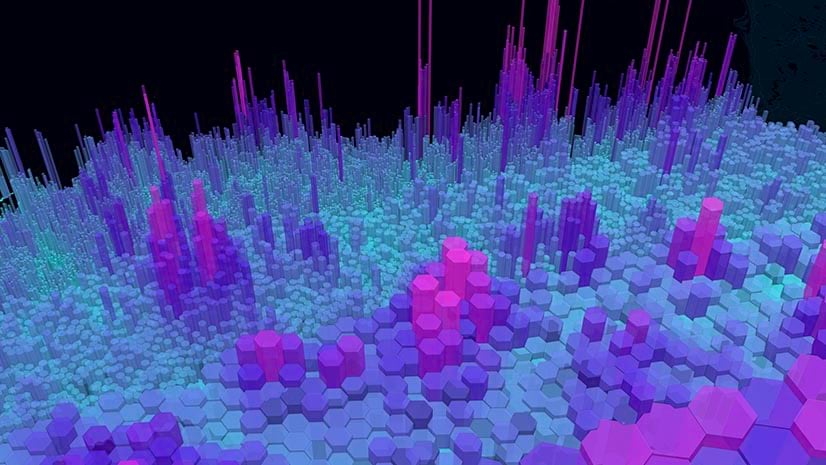

A geographic approach supported by GIS technology allows energy professionals to contextualize assets like platforms and pipelines in light of the new roles they could play.

“In achieving even the first set of goals, spatial planning is going to be critical,” says Carlo Procaccini, head of technology at the NSTA, formerly the UK Oil and Gas Authority. Those first steps include identifying reservoir locations best able to store CO2 undersea, advising companies interested in leasing those areas, and ensuring that operations align with other energy transition initiatives like platform electrification.

In another repurposing effort under way in the Gulf of Mexico, location analysis is helping organizations lay the groundwork for converting offshore oil rigs into hubs for fish farming, also known as aquaculture. Petroleum industry veterans who once used GIS analysis to guide oil and gas exploration are now employing the technology to assess which retired rigs would best support populations of red drum and other fish.

The concepts of carbon capture via existing pipelines and oil rig aquaculture have been around for years. Now, economic incentives, the global urgency to address climate change, and technological advances have aligned to make these initiatives both possible and desirable.

“It definitely feels like over the next five years, this is going to go from idea to reality,” says Tyler Sclodnick, principal scientist for Innovasea, one of the companies leading the rig aquaculture effort in the Gulf of Mexico. “We’re not talking about concepts; we’re talking about specifics. We’re looking at maps, saying, ‘This is exactly where it’s going to be, this is specifically what we’re going to farm, this is the equipment.’”

Achieving Speed and Efficiency through Spatial Planning

In both reuse cases, location intelligence empowers business leaders to make data-driven decisions quickly so they can leverage infrastructure before it’s decommissioned. GIS also plays a key role in assessing the cost-effectiveness of a project, by assimilating data from multiple sources to overcome logistical challenges and avoid expensive missteps or delays.

Repurposing infrastructure means companies can defer the cost of dismantling equipment, and obviates the need to invest in new transportation or storage facilities.

“If you know underground storage sites because you have operated them as oil and gas assets for 20, 30 years, you’re aware of the surface risks much better than [if you’re] developing new storage sites,” Procaccini says. “Reusing and repurposing could be better for costs, better for knowledge, and better for risk management.”

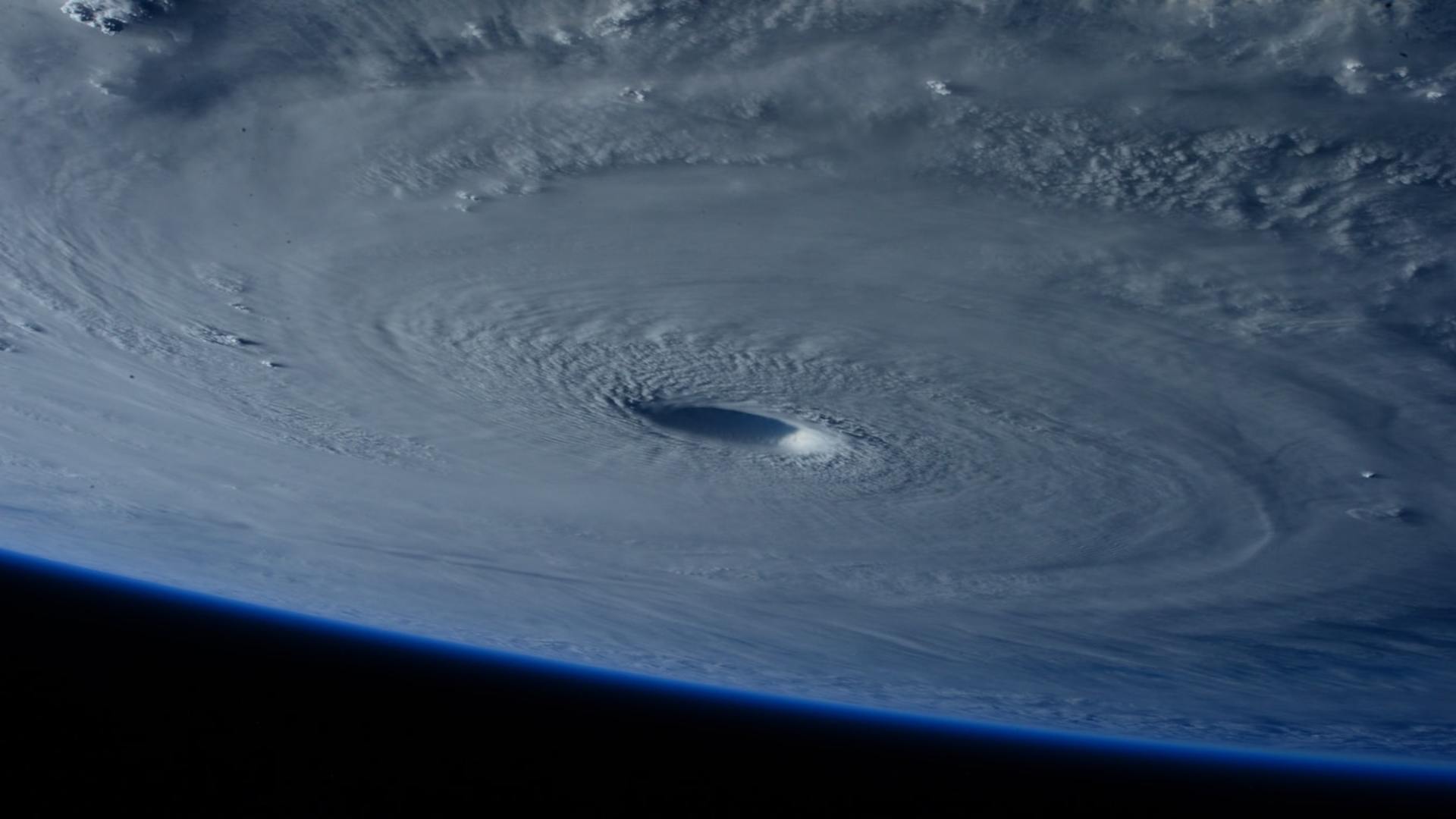

Location analysis indicates that the UKCS has enough CO2 storage capacity to lock away the country’s carbon emissions for hundreds of years. Since the UK will rely on fossil fuels until it can fully transition to cleaner power like wind and solar, this effort will help erase emissions resulting from continuing hydrocarbon use. The target for the first phase of carbon capture is to sequester 11 million tons of carbon dioxide every year by 2030.

It’s not just a 2D spatial problem; it’s a 3D spatial problem.

The Biggest Undersea Treasure Trove: Data

The ability to unlock new business value from data collected on old hydrocarbon assets is key to implementing these transition strategies. The NSTA is using GIS to map and analyze five decades of data gathered by oil and gas companies, resulting in a comprehensive picture of the surface, subsurface, and seabed environments. This 3D portrait helps the agency highlight the most efficient and economical ways to connect industrial-scale sources of CO2 onshore with undersea reservoirs.

“When you look at all of this in the round, it is very much a spatial problem,” says John Seabourn, chief digital officer at the NSTA. “There’s no point in having a reservoir somewhere [where] you can pump CO2 if you can’t get it there in the first place.”

The authority has awarded six licenses for undersea carbon storage to date, and carries out a sophisticated vetting process to ensure that proposed sites can store carbon effectively. Decision-makers must consider data on variables including geologic structure—reservoirs have to be topped by impermeable caprock that traps the liquified gas—and how the pipe itself might behave when it transports CO2 instead of a hydrocarbon.

The operational awareness gained from GIS helps NSTA leaders anticipate and avoid conflicts with other ocean-based business interests like fisheries or offshore wind farms. Dashboards can show the locations of sensitive environmental areas, such as marine mammal habitats, or archaeological sites. Understanding the layout of the ocean floor is also crucial to the success of carbon capture and storage projects. Sensor data gathered from wellbores can indicate how wells were abandoned and plugged.

GIS interlaces all these forms of data to refine risk assessments and rank the carbon storage capacity of reservoirs, giving participating companies the greatest chance of success. It’s an example of how location intelligence can bring together the resources of public and private sectors to create better climate outcomes. Other examples include efforts to predict weather outcomes decades in advance and plan equitable distribution of electric vehicle chargers.

Once you are in GIS, you want to continue using it and you want to expand the functionality.

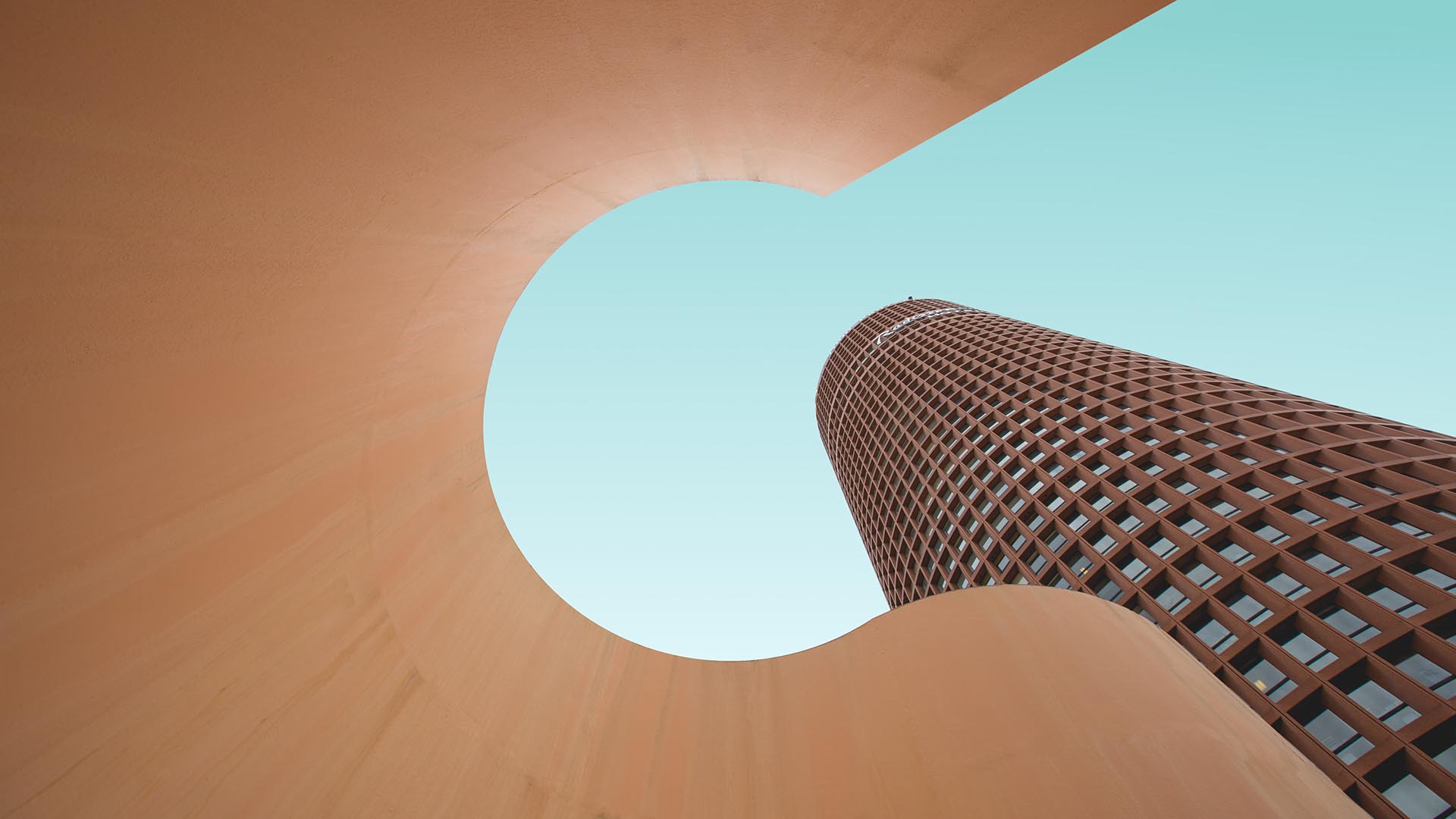

A New Purpose for Idle Iron

The Gulf of Mexico is similar to the UKCS in its hydrocarbon lifecycle. The nearly 1,800 oil platforms dotting the waters off the coast of Texas are largely the artifacts of a hydrocarbon industry that boomed in the 1970s and 1980s and began to slow in the 1990s.

Once a platform ceases production, US law stipulates that it must be decommissioned within a year. According to one estimate from the energy consultant Wood Mackenzie, decommissioning wells in the Gulf of Mexico could cost a billion dollars per year through the next half decade.

That’s why the current partnership between the Gulf Offshore Research Institute (GORI) and aquaculture firm Innovasea is attracting attention from oil and gas firms with “idle iron” in the sea. GORI and Innovasea’s plan to reclaim rigs as centers for offshore aquaculture could save operators the trouble of decommissioning—and ultimately help turn a profit.

A Glimpse—and Taste—of a Greener Offshore Future

Innovasea specializes in creating high-tech pens for fish farming, a means of raising healthy protein, which releases far less carbon dioxide than meat production does. Adapting rigs to aquaculture could help oil and gas companies meet net-zero goals, while giving operators a platform on which to run farms and feed fish without making long journeys by boat to the pens each day.

Location intelligence equips project leaders with insight into how existing rigs could help aquaculture flourish. Smart maps integrate sensor information about the movement of currents with data about the ocean floor. Satellite images can enrich the analysis with data on chlorophyll levels and surface temperatures. All these complex variables can affect the health of fish and the success of offshore farms.

“It takes a lot of things to align to say, ‘This project can go ahead,’ both from an environmental standpoint and just commercial feasibility,” says Innovasea’s Sclodnick. By contextualizing these data layers, GIS helps identify areas where projects can move ahead free from conflict with regulators and other marine stakeholders.

Innovasea and GORI are focusing their analysis on two Gulf of Mexico platforms, but they estimate that many of the rigs—perhaps hundreds—could be suitable for aquaculture and other marine-related purposes. When Kent Satterlee, executive director at GORI and a 35-year veteran of Shell, dove underwater at one platform called Station Padre, he saw firsthand what the future of the oil rig could be.

With visibility out to 100 feet that day, he saw swarms of ornamental fish, red snapper, and barracuda swimming amid the coral-covered legs of the platform. The biodiversity that such rigs encourage offers another benefit: building ecosystems that help integrate fish pen farms into the natural setting.

How Data Analysis Powers Efficient Innovation

While these carbon capture and transition strategies might seem boldly innovative, they testify to the truism that necessity is the mother of invention. These reuse projects are a cost-effective, low-risk means of adapting hydrocarbon assets to a lower-carbon future. The transition benefits from existing physical assets—pipelines and platforms—as well as the data that empowers infrastructure operators to play new roles in meeting net-zero ambitions.

Location intelligence puts energy leaders in charge of this process. “That’s what you want when you work in a digital and data environment,” Seabourn says. “You always want to be pushing that boundary a little bit and seeing what you can do with the technology to support complex decision-making.”