A war quietly ended in Oregon earlier this year. After decades of costly political battles and adversarial behavior, the state’s timber industry and environmental groups reached an accord. The two sides—represented by 13 timber companies and 13 conservation groups—agreed to withdraw competing ballot measures and spend the next 18 months developing new rules for logging on private land in Oregon. Kate Brown, the state’s governor, called the agreement historic and extraordinary.

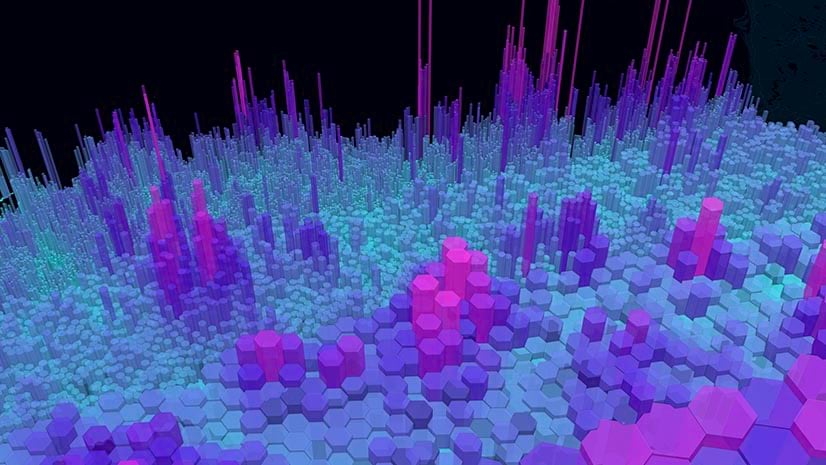

Private land in Oregon designated as timberland—forests that can produce commercial-grade timber—covers nearly 25 percent of the state, an area the size of West Virginia. For years, natural resource companies have used location technology to manage activities in vast forests, underground gas fields, and offshore wind farms. Now, a geographic information system (GIS) could help the Oregon parties share an understanding of critical areas as they plot out activities under this pivotal agreement.

Visualizing the Problem

As a first step in the Oregon compromise, both sides are urging state lawmakers to pass tougher rules on aerial herbicide spraying—including establishing larger buffer zones around schools and homes—in a move supported by even the timber industry’s most ardent defenders. This will require the two sides to calculate buffer zone boundaries and produce maps to share with the public.

Farmers and resource managers routinely use GIS to create and enforce buffer zones. Some agricultural equipment now automatically closes spray nozzles when the machine crosses into a protected zone.

Pennsylvania is in the midst of a project with a focus on buffer zones. To create 95,000 new acres of forests near streams, officials are using GIS to analyze existing terrain and calculate the necessary buffer zones between tree lines and stream banks.

More generally, the location intelligence produced by GIS can help partners—even former adversaries—negotiate around a single, data-based reality. In essence, technology helps ground-truth assumptions when it’s important to measure what happens in certain locations.

Understanding the Needs of All Stakeholders

For years, the relationship between the environmental movement and the timber industry in the Pacific Northwest has been framed as a zero-sum choice between conservation and jobs. The new Oregon accord is notable for the industry’s pledge to further the region’s biodiversity. Moving forward, timber companies have said their actions on private lands will not threaten endangered species—particularly salmon, which have disappeared from many of the region’s waterways.

In practical terms, devising these types of plans means weighing the complex concerns of many stakeholders. Oregon’s challenge echoes those found in some developing nations where land use is not well-defined. There, the solution often begins with a data-driven map around which stakeholders can communicate and negotiate.

For instance, a nonprofit organization has helped land managers in Cambodia control rampant deforestation. Using location intelligence technology, stakeholders worked together to build maps that balance “private sector interests in cash crops, timber, and textile mills . . . with Cambodia’s need to feed its people and protect its natural resources,” according to a recent article.

In other parts of the world, land managers are driving GIS-based ground-truthing a step further. Using artificial intelligence models, forest managers in Finland are filling out a meticulous inventory of forests, giving landowners insight on the location of certain species and creating a map that will help automated machines harvest wood without human intervention.

Mapping the Road Ahead

As the two sides in Oregon work together on a forest management plan, they’ll want to ground truth their decisions with reliable and detailed data about specific locations. Although they will be discussing forestland, they might take cues from recent developments in urban planning.

City planners now routinely use location intelligence to better understand and manage explosive growth (as in Seattle and San Francisco), disruptive trends (e.g., the influx of short-term rentals squeezing a tight housing market in Honolulu), and smart city features such as those found in Boston, where urban planners used GIS technology to produce a digital twin of the metropolis. Similarly, some timber companies have already built “digital forest” models, using remote sensing and the Internet of Things (IoT) to decide how best to manage their lands. Such models can provide valuable insight as companies manage resources and collaborate with organizations around a common truth.

For everyone involved in the Oregon accord, the next year and a half will require cooperation and compromise. A shared location intelligence strategy will help each side understand the other along with the resources in question. Even if the groups don’t always see eye to eye, location intelligence can help them see more clearly and shape crucial conversations.