The designer and information architect Richard Saul Wurman employs an acronym—LATCH—as a reminder that there’s just a handful of ways to organize information. It stands for Location, Alphabet, Time, Category, and Hierarchy. As a cartophile I’m naturally drawn to the “L” for location. The ancient art of cartography, and the modern science of geographic information systems, are expressions of the power of location, not just to organize information but to discern patterns, influences, and interrelationships.

For an item to be organized by location, it needs to be georeferenced. Georeferencing can be defined narrowly as the process of assigning a coordinate system, often to a raster image, that allows it to be related it to real locations on the Earth’s surface. But georeferencing has a broader meaning; as Wikipedia puts it, “Georeferencing means to associate something with locations in physical space.”

Note the plural, “locations.” Things can be associated with multiple locations. A cell phone is composed of parts and raw materials that originated from many corners of the world. A Renaissance painting might have been created in one location, but its provenance might trace its history across two or more continents.

I’ve long had a weird fascination with georeferencing, and in particular the notion that an object might be most closely associated with two key locations: Where it was created, assembled, or occurred in the wild, and where it resides now. This notion of double georeferencing is potentially, and especially, useful to museums, zoos, and aquariums. Location reference number one is to an item’s postion within the institution that maintains or displays it; the second records that item’s original location. In the case of a plant or animal, the second reference is an area, namely a range map. For a work of art, it’s the point, or place, where the artist created the piece.

Double georeferencing in action

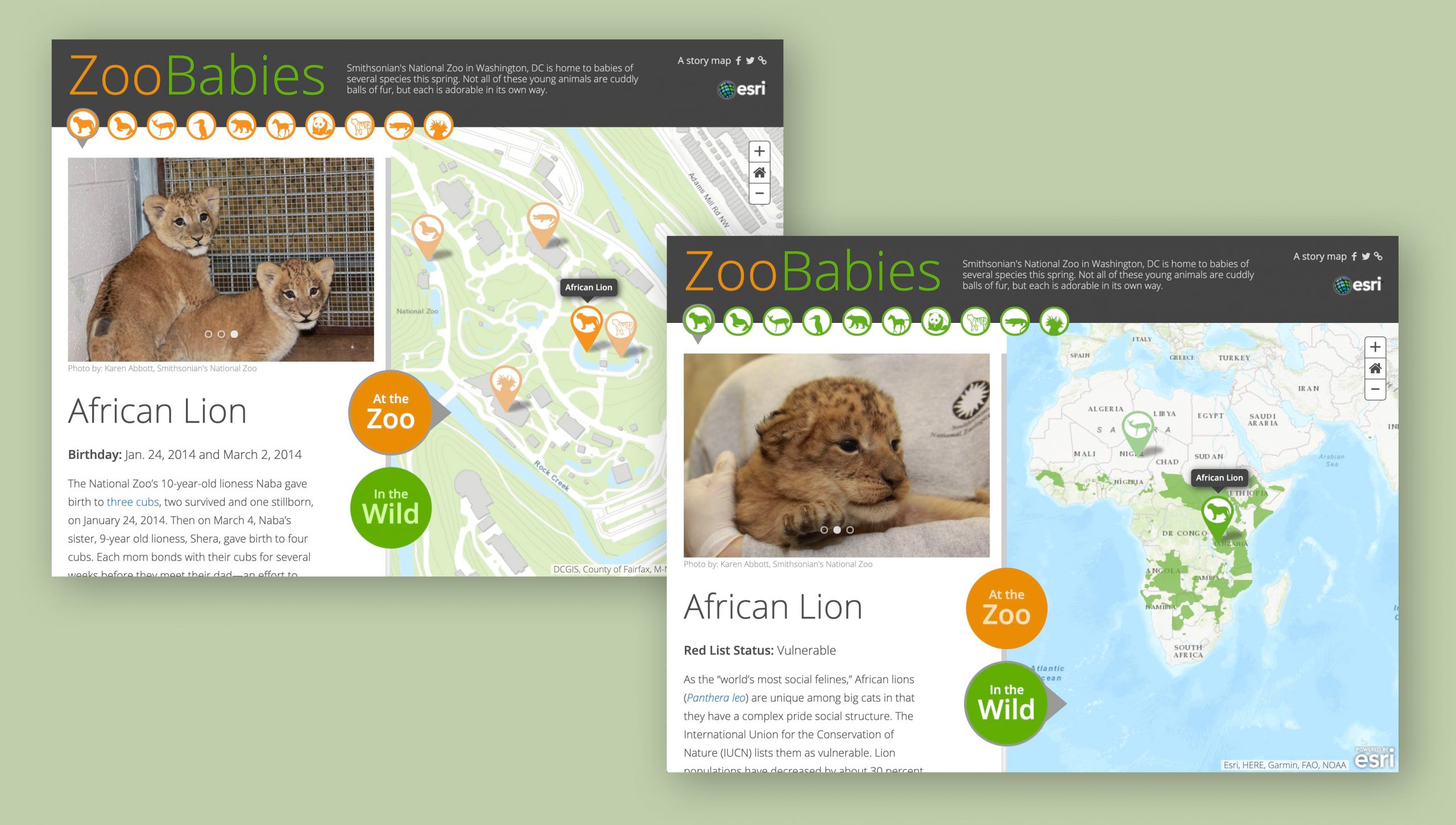

Several years ago, my team conducted a little experiment in double georeferencing. We thought it would be fun to locate a selection of animals within the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington, DC, and also locate where those animals occur in the wild. And since we all love baby animals, we decided to feature young animals. Thus was born “Zoo Babies.” We chose ten critters—all of them now grown-ups, no doubt—and included a portrait and description of each.

One of the featured animals, the Micronesian kingfisher, is extinct in the wild, and two, the Dama gazelle and the Cuban crocodile, are critically endangered. Those facts reveal our ulterior motive: to slip a conservation message into a charming and entertaining story. Rather than pound people over the head with a hand-wringing sermon on the threat of mass extinction, why not charm readers with infant animals, then gently inform them that in the future there may be no more babies?

A caveat: The Zoo Babies story is a one-off, custom effort. You can’t currently reproduce its user experience using either ArcGIS StoryMaps or classic apps. But it is possible to tell stories featuring double-georeferenced items using our standard ArcGIS StoryMaps builder.

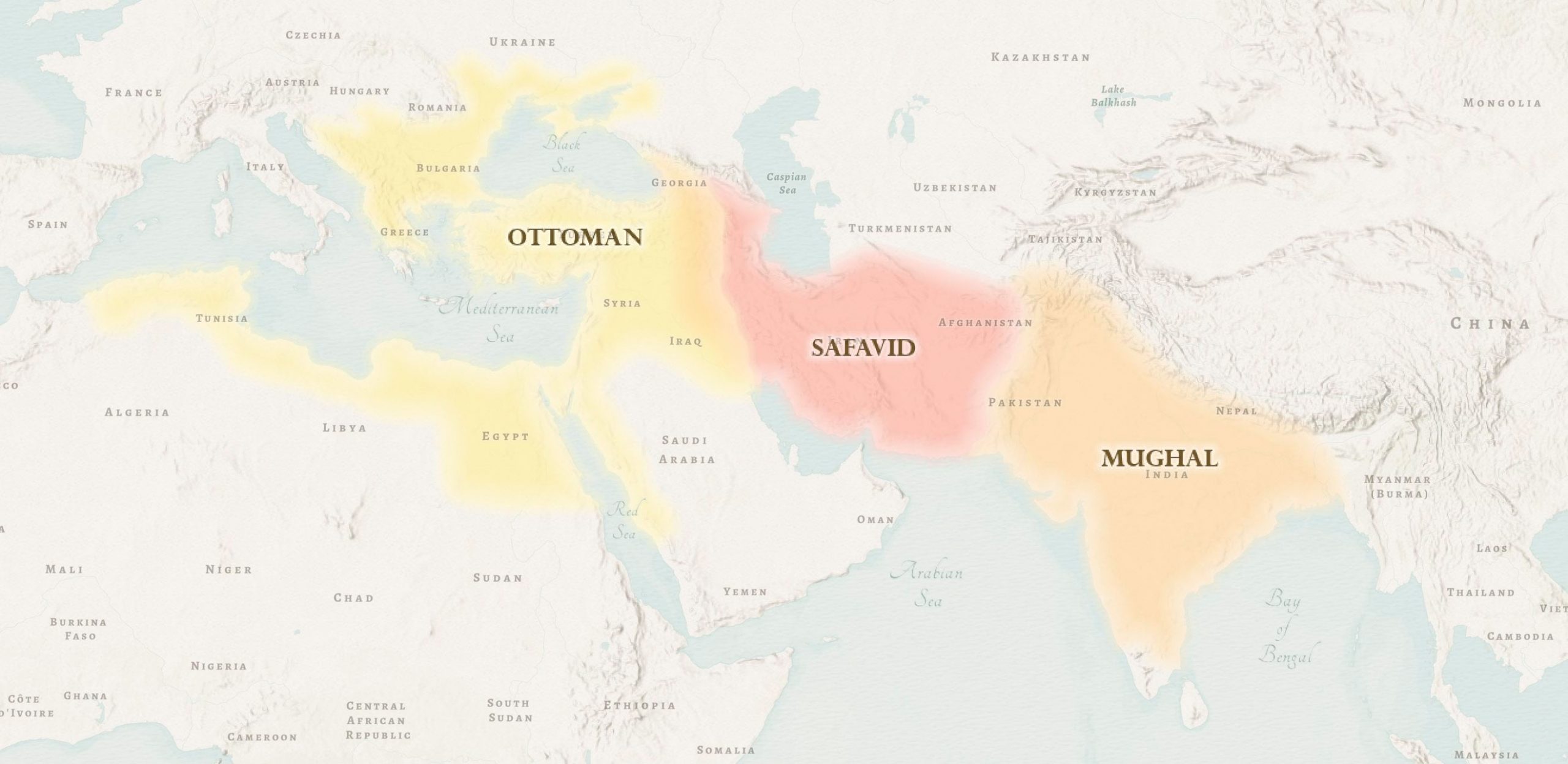

Much more recently we returned to the topic of double georeferencing in collaboration with Sharon Kitchens, a colleague at Esri’s Portland, Maine, office who loves the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. She also loves story maps, and is working with us on an occasional series of stories we’re calling “The Art of Where.” She visited the Met’s Islamic art galleries, and worked with a curator to feature its collection. The story includes two sets of maps: one guides visitors through the Met’s maze of corridors and exhibit spaces to locate the Islamic galleries; the other depicts three historical Islamic empires—the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal—and locates the places of origin of some of the pieces on display at the Met.

The maps of the Met’s interior serve the everyday needs of navigation and orientation. The historical maps do much more. They remind us that Islamic art arose across a broad region that bridges the cultures of Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia, and that artistic styles arose and evolved in the context of a complex network of trade routes. Artisans of western Turkey were influenced, for instance, by potters in Ming-dynasty China, thousands of miles to the east. The maps remind us that globalization isn’t a recent phenomenon, and that the interplay of cultures might create geopolitical conflict, but that it can also create and enrich artistic expression.

My judgment might be colored by my strange obsession, but I think double georeferencing provides multimedia storytelling opportunities that could benefit all sorts of museums, zoos, and aquariums. Why not take advantage of the quotidian needs of locator maps to provide a parallel guide to the broader world, putting objects and collections in geographic context and inviting visitors to gain new insights?

Article Discussion: